The Kaula traditions – I

Who, or what, are the Kaula traditions? It’s a question that has bedeviled me ever since I read the teasing footnote references to “Kaula comment” in Kenneth Grant’s Typhonian trilogies back in the early 1980s. In Cults of the Shadow (Frederick Muller, 1975) for example, Grant made several references to the “Kaula Cult of the Vama Marg”, its secret rites and esoteric sexual practices. It seemed to be all very secret, hush-hush, and confusing. Over the years, I’d occasionally find people throwing the term Kaula about in various forums, and would ask them what the “Kaula Cult” actually was. It was hard to get a straight answer, and I often came away with the impression that these folk didn’t really have much of a sense of what the Kaulas actually consisted of, much less be able to point to a particular historical tradition or scripture.

Since I’ve recently been posting about early tantric traditions (see posts tagged: vāmācāra) I thought this would be a good opportunity to get my thoughts in order about the Kaula traditions. As I’ve intimated, this is a difficult subject to get to grips with, as even in the scholarly literature there is a great deal of conflicting information about these traditions. It is often unclear whether they are a subset of different tantric streams or an entirely separate development. One complication is that some tantric traditions have both non-Kaula and Kaula forms, and some later Kaula scriptures go as far as to denounce tantric practitioners – viewing their scriptures as a higher revelation than that contained in the tantras. It also seems to be the case that Kaula became, over time, a synonym for any text of practice which was goddess-oriented and transgressive.

Fortunately, I’ve been able to clarify the matter a great deal by referring to the work of Alexis Sanderson. His monumental essay The Śaiva Literature sheds much light on the relationship between the Kaulas and the tantric traditions 1 – although be warned, it’s not exactly an easy read. Mike Magee once said to me that trying to distinguish between different tantric traditions was like “herding cats” – but I shall do my best.

If I’m understanding Sanderson’s work (and those scholars who follow him) then the Kaula streams emerged out of the goddess-oriented Vidyāpīṭha stream (see this post).

The term Kula means a clan or family. In the earlier traditions, such as the Yāmala, a practitioner would, through initiation, become a member of a clan of Yoginīs. But a new esoteric concept of Kula emerged to signify both the human body and the cosmos as being composed of a network of female powers. By envisioning the body in this way, much of the ritual practice of the mantramārga became internalized. So for example, instead of going on a lengthy and costly pilgrimage to sacred sites across the subcontinent, a practitioner could install those sites within his or her own body and perform the appropriate worship. The human body hence became the primary seat of worship for all powers and capacities, rather than the cremation ground or other wild places. At the same time, the goddesses became identified with the senses and other capacities of the human body. So for example, everything one hears can be a continual offering to delight the goddess of hearing.

Although the Kaulas took up practices such as sexual intercourse with a ritual consort, the consumption of bodily ‘nectars’, and ritual offerings such as meat and alcohol, these were eventually not seen as ends in themselves, but rather, they were means to access an expansive, blissful consciousness. At the same time, many rituals were simplified, and there was more of an emphasis on ecstatic experience, and yogas that did not seek to suppress the senses. By moving the focus of practice away from the cremation ground and other wild places, there emerged eventually an aestheticized practice that was more acceptable to householders and courtly elites.

The Kaulas developed into four main systems which became known as the Four Transmissions (āmnāya) – divided into the four main directions. Each system developed its own deities, maṇḍalas, scriptures, ritual manuals, etc.

The Eastern Transmission (Pūrvāmnāya)

The first of the Kaula streams, the Eastern Transmission was initially focused on the worship of Kuleśvara and Kuleśvarī, the god and goddess of the Kula, surrounded by layers of subsidiary deities such as the eight mothers, and other entities, including clans of Yoginīs. It is from this current that emerges the Trika tradition – possibly prior to the eighth century. The Trika tradition was focused on the worship of three goddesses, the gentle and sweet-natured Parā, and two fierce, Kālī-like aspects of Parā – Parāparā & Aparā. These three goddesses were to be visualized as seated upon lotus-thrones positioned on the tips of a trident (the primary weapon of Śiva) which was, in turn, coextensive with the adept’s spine. It’s foundational scripture was the Mālinī-vijaya-uttara-tantra.

To the worship of these three goddesses was later added an esoteric form of Kālī – Kālasaṁkarṣiṇī (“Destroyer of Time”) who transcends the three goddesses. A further development was the Kaula mode of the Trika, said to have been founded by a female teacher. 2 In the ninth century, further developments of Trika thought were the Śivasūtra (“Aphorisms of Śiva”) and the Spandakārikā (“Concise Verses on Vibration) which expounded the doctrine of spanda as the essential nature of the deity. This developed into a sophisticated theology that became known as the pratyabhijñā – “recognition” school, where salvation is the “recognition” of one’s own identity with Śiva.

These various developments are synthesized in the works of the great master Abhinavagupta; Tantrāloka (“Light on Tantra”), the Tantrasara, and his commentary on the Parātriśikā-tantra the Parātriṁśikāvivaraṇa. This nondual phase of the Trika tradition is sometimes referred to as “Kashmir Śaivism”.

Abhinavagupta declares in Tantrāloka:

“This the supreme Lord declared in Ratnamālā (Tantra): the essence of all Tantras, present in the right and left traditions, and which has been unified in the Kaula (is to be discovered) in the Trika. The ritual is overemphasized in the Siddhānta, which moreover is not free from the taint of māyā, and other things. The right tradition abounds in awesome rites, whereas in the left one supernatural powers (siddhis) are predominant. Keep far away from those disciplinarian texts, which bring little merit and much affliction, which no personal intuition illuminates, and which are lacking in wisdom (vidyā) and liberation (mokṣa).”

(TÄ 37.25-28) 3

The Western Transmission (Paścimāmnāya)

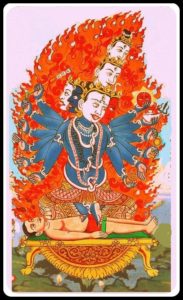

The Western transmission is that of Kubjika – the “hunchback goddess”. She is visualized as black in colour, large-bellied, six-faced, twelve-armed, and wearing serpents, gems, human bones and a garland of skulls. She is the personification of kuṇḍalinī. The earliest evidence we have for the Kubjika is from the tenth century, and it was influenced by both the Trika and the Krama systems. It’s in this tradition that we first see the system of the six chakras that later appears in Hatha Yoga

The Western transmission is that of Kubjika – the “hunchback goddess”. She is visualized as black in colour, large-bellied, six-faced, twelve-armed, and wearing serpents, gems, human bones and a garland of skulls. She is the personification of kuṇḍalinī. The earliest evidence we have for the Kubjika is from the tenth century, and it was influenced by both the Trika and the Krama systems. It’s in this tradition that we first see the system of the six chakras that later appears in Hatha Yoga

The root text of this tradition is the Kubjikāmata tantra. In 2009, Dr. Mark Dyczkowski published a translation of another Kubjika scripture – the first book of the Manthānabhairava Tantra –it consisted of 14 large volumes and this was the result of twenty years of labour – which gives you some indication of the lengths which scholars of these traditions go to!

The Northern Transmission (Uttarāmnāya)

The Northern transmission consisted of three traditions – the Mata, Krama, and Guhyakālī currents – all of which involved the worship of esoteric aspects of Kālī.

Krama means “sequence”, and the tradition is focused on twelve forms of the goddess Kālī, each of which embodies a stage in the arising or falling away of cognition. As Christopher Wallis points out in his book, Tantra Illuminated, the Krama tradition is something of a paradox. One the one hand, the Krama taught transgressive practices including orgiastic worship, but on the other, it rejected much of the ritual processes and requirements of earlier traditions, including most forms of post-initiatory observances, and the requirements to perform rituals at specific times of the day or according to the phases of the moon. The tradition produced highly sophisticated literature, little of which has so far been translated.

The Southern Transmission (Dakṣiṇāmnāya)

The Southern transmission was originally the propitiation of Kāmeśvari, accompanied by Kāmadeva and a group of 11 goddesses known as the Nityās. Out of this tradition there developed Srīvidyā, centered around the propitiation of the goddess Lalitā Tripurasundari. Lalitā means “the playful one” and Tripurasundari – “She who is beautiful in the three worlds”.

The goddess is worshipped in visualized forms, in her sound form as mantra, and as the Srī chakra or Srī Yantra. Lalitā is beautiful, sweet-natured, red in colour or wearing red garments, and bears in her four hands an elephant goad, a noose, a bow made of sugarcane and five flower-arrows.

The root text of the tradition is the Vāmakeśvarīmata tantra, which has been dated to the eleventh century. Srīvidyā of course has survived to the present day, although it does so in a domesticated forms where the original Kaula elements have been muted. This quote (one of my favourites) from the Saundaryalahari expresses sentiments in accord with ideas expressed in other Kaula texts – that the best way to worship one’s chosen deity is not through formal ritual but in everyday activities.

“Let my idle chatter be the muttering of prayer, my every manual movement the execution of ritual gesture,

my walking a ceremonial circumambulation, my eating and other acts the rite of sacrifice,

my lying down prostration in worship, my every pleasure enjoyed with dedication of myself,

let whatever activity is mine be some form of worship of you.”

The problem of the “Yoginī-Kaula”

A wide variety of texts and practices have been attributed to the Yoginī-Kaula stream, supposedly founded by Matsyendrendranātha. However, as Shaman Hatley points out the identification of the Yoginī-Kaula current stems from a misinterpretation of the term yoginīkaula as it occurs in the Kaulajñānanirṇaya. It was interpreted to refer to a particular sect or school, whereas, according to Hatley, it should be interpreted as referring to “esoteric knowledge associated with or possessed by Yoginīs.” 4

That’s all for now. I will at some point return to the Kaulas and attempt a deeper dive into the complexities of these traditions.

Sources

Shaman Hatley, The Brahmayāmalatantra and Early Śaiva Cult of Yoginīs (Ph.D thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 2007)

André Padoux, Vac: The Concept of the Word in Selected Hindu Tantras (State University of New York, 1990)

André Padoux The Hindu Tantric World: An Overview (University of Chicago Press 2017).

Alexis Sanderson The Śaiva Literature Journal of Indological Studies, Nos. 24 & 25 (2012-2013)

Christopher Wallis Tantra Illuminated: The Philosophy, History, and Practice of a Timeless Tradition (Mattamayūra Press. 2013).

2 comments

Martin Jelfs

Posted September 15th 2020 at 10:06 am | Permalink

Thanks for this Phil; I always wondered about the different streams of the Kaulas.

William

Posted September 15th 2020 at 3:22 pm | Permalink

Thank you Phil. Your clear summaries and explications earn you great merit and my reverent gratitude.

William