Edward Sellon and the Cannibal Club: Anthropology Erotica Empire – VI

In the third installment of this series, I examined the erotic writings of Edward Sellon. Now I will turn to his “anthropological” work – the two lectures delivered to the Anthropological Society of London (ASL) – Linga Puja: On the Phallic Worship of India and Some Remarks on Indian Gnosticism, or Sacti Puja, the Worship of the Female Powers and follow through with a look at some other works dealing with Phallic worship from the ASL.

On the Phallic Worship of India

Sellon’s 1865 paper on the Phallic Worship of India read to the Anthropologicals by one of his friends caused much comment amongst the Society and beyond. In the introduction, he states:

“It has been the practice of missionaries to burke (i.e. to avoid) the question of Linga Puja, from a mistaken and false delicacy. It is trusted, however, that the members of the Anthropological Society will not be offended, if, in consideration of this subject, a spade is called a spade, and not a rake or a hoe.”

Sellon describes the Lingam and says that it represents the union of the sexes, the divine shakti, the procreative, generative force throughout nature. He goes on to describe village rituals whereby young women who are “anxious for lovers or husbands” deck the Lingams with garlands of flowers. He discusses the beliefs of various religious groups such as the Saivas and the Vaishnavas, and again, the Sactas. Providing a list of twelve sites where, according to the Kedara Kalpa of the Nahdi-upa-Purana Siva is especially present in the form of a Linga, Sellon remarks that “From this circumstance there can be little doubt that the religion of the Saivas, or followers of Siva, is nothing more than a gross system of Phallic idolatry.”

He points out that Hindus do not consider the Linga worship to be obscene, and speculates that all Phallic worship may have originated in India, and moved from India to Egypt, to Syria and from there to Greece and Rome. He further points out that the Cult of the Phallus is not only something that existed in large parts of the world in antiquity, but is still “an integral part of worship” in India, Tibet, China, Japan, Southern Africa, and – possibly – in numerous other countries too. He ends with the startling statement that “there would now also appear good ground for believing that the Ark of the Covenant, held so sacred by the Jews, contained nothing more or less than a Phallus”.

A reviewer of this lecture in the Journal of the rival Ethnological Society scornfully dismissed this latter idea as “wild, absurd, and improbable”. Within the Anthropological Society however, the paper stirred a spirited discussion. Was Phallic Worship linked to Race? Was it something that disappeared as races developed? Was it something sacred or was it associated with “obscene notions”? A doctor Seeman opined that he had seen many phallic stones in his travels to the South Seas, but it wasn’t until he saw phallic images in India and Italy that he came to understand their meaning. His belief was, that the obelisks of Egypt were intended for nothing more than phalli, and that the columns of the Grecian temples are nothing but a collection of the same. Other attendees debated the relationship between phallic and snake worship, and whether such beliefs could be traced in present-day Christianity. These discussions reflected a growing interest in the theory that all societies progressed through a series of developmental stages. Contemporary “primitive” cultures began to be viewed as important sites for discovering the processes by which societies developed. Richard Burton, in an account of his visit to the African Kingdom of Dahomey described what he called “the Dahoman Priapus”, noted its similarity to Japaneses Priapic figures, and commented that “I could have carried off a donkey’s load had I been aware of the rapidly rising value of phallic specimens amongst the collectors of Europe.” 1

“Sacti Puja”

Some Remarks on Indian Gnosticism, or Sacti Puja begins with the observation that “Fanaticism, no matter to what creed it may appertain, has, in all ages and countries, paved the way for Licentiousness.” Sellon then goes on to explain the principles of Saktism, or Power, which he says, originated with the “austere principles of the Shaiva and Vaishnava Codes of the Ancient Hindu Faith”. According to Sellon, the Shakti creed acknowledges deities such as Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva but holds them to be subordinate to the “great goddess.” He notes that “The worshippers of Sacti, or power, who possess numerous books in Sanscrit verse, have been gaining ground in India for some years, but have lately sustained a check at Bombay, which may ultimately lead to their suppression.” This is a reference to the 1862 Maharaja libel case (see this post for more details).

Sellon points out that the creed is set forth in “remarkable and recondite volumes called Tantras” and that the term Tantram “signifies, literally, art, system, craft, or contrivance, prescribing the abolition of all caste, the use of wine, flesh, and fish, with magical arts, diagrams, and the express adoration of the female sex.”

He continues: “it is required that the woman be looked upon as actually and truly a goddess (for the time) and that the devotee is regarded as the divinity who is worshipping her. Curses are denounced upon him who looks upon her as a woman, or himself as a mortal during the performance of the rite.” He follows with a blow-by-blow account of the chakra or shakti puja, and that the male devotee “adores, in imagination, every individual part of her person, and by incantation, lodges a fairy in every limb and member, and one in the Yoni, or centre of delight. The names of the female sylphs addressed to her are not very delicate, and need not be here further alluded to.”

Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, descriptions of “Sacti Puja” had become a popular example of evidence of Hindu licentiousness and depravity. The French Missionary Abbe Dubious in his 1807 Hindu Manners, Customs and Ceremonies had described “Sacti Puja” as involving “the grossest immorality” and “the most revolting orgy”. The Reverend William Ward, in his A View of the History, Literature, and Mythology of the Hindoos summed up the chakra worship of women as “things too abominable to enter the ears of man, and impossible to be revealed to a Christian public.” (See this post for a discussion of Ward and his works).

Sellon provides extracts from a number texts, such as the Yogini Hridayam (he translates the title as “Heart of the Nun”), the Yoni Tantram (“Ritual of Vulva Worship”), the Ananda Tantra (“System of Joy”) and the Acasa Bhairava Tantra – although some passages are given in Latin.

That Sellon describes this tantric mode of worship matter-of-factly – and goes on to suggest that there may be similar rituals in the Greek Eleusinian mysteries – is striking. Particularly as the majority of European scholars of the time regarded anything to do with the tantras as a clear sign of Indian immorality and religious perversity. Sellon’s paper may be the first wholly positive article on the subject of the tantras from a European.

In his conclusion to Sacti Puja Sellon mentions that much of his information for the paper has been derived from a “very learned orientalist” – but that personage “made it an express condition that his name should not appear”. Sellon says that his source was a member of the Madras Civil Service for 30 years, a judge, and a man of letters. Who was this “very learned orientalist”? Jon Lange, in his 2017 book Sellon’s Annotations – which brings together both of Sellon’s papers to the Anthropological Society and his Annotations on the Sacred Writings of the Hindus has examined the various candidates, and after extensive research, proposed that the “orientalist” was Charles Philip Brown (1798-1884), who fits all of Sellon’s criteria, having been a judge, and a civil servant residing in India. Brown was also co-editor of the Madras Journal for a number of years, an accomplished translator of Telegu, and a collector of manuscripts. 2

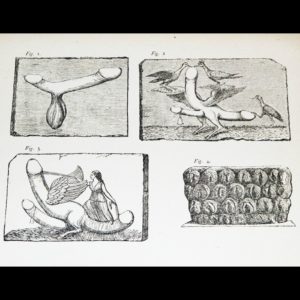

That same year (1865) saw the republication of Richard Payne Knight’s A Discourse on the Worship of Priapus by John Camden Hotten of Piccadilly (see this post for a discussion of the themes of Discourse and this post for a short biographical sketch of Richard Payne Knight). It is sometimes assumed that because Hotten sold obscene literature such as Lady Bumtickler’s Revels, that he was as disreputable as William Dugdale (see this post for more about Dugdale). But Hotten also published the works of Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, and Swinburne. To this new edition of Discourse was added a new work – Thomas Wright’s On the Worship of the Generative Powers in the Middle Ages – written with the assistance of J.E. Tennent and George Witt, making this new edition of Discourse an Anthropological Society project. Thomas Wright (1810-1877) was a founder member of the British Archaeological Association and a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London. Wright’s rather plodding, scholarly essay examines a wide range of phallic objects found across Europe – often of Roman origin and related to the worship of Priapus. He also discusses the “Shelah-Na-Gig monuments found on Irish churches, describing them as “a female exposing herself to view in the most unequivocal manner” and says that they were intended as protective charms against the evil eye. Phallic amulets found at various sites are treated to a lengthy discussion, as are the festivals dedicated to Priapus – “licentious orgies” – and their survivals. Both the Knights Templar and the Witches Sabbath are also examined at some length. It is Wright’s essay that would be later cited with much approval, by twentieth-century occultists such as Aleister Crowley, Gerald Gardner and Dion Fortune.

Further Phallic Publications

The Anthropological Society of London’s interest in Phallic antiquities continued with two other essays: “On Phallic Worship” by Hodder Michael Westropp and “The Influence of the Phallic Idea in the Religions of Antiquity” by Charles Staniland Wake. Both essays were published together in 1875 by Trubner and co. of London as “Ancient Symbol Worship: Influence of the Phallic Idea in the Religions of Antiquity”. Westropp (1820-1885) is mostly remembered for his publication (in 1867) of the first Handbook of Archaeology, and for his introduction and definition of the term “Mesolithic” in 1872. Wake (1835-1910) was the first director of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland – a body formed in 1871 when the ASL amalgamated with its former rival, the Ethnological Society. He later emigrated to the United States, where he edited the 1893 Memoirs of the International Congress of Anthropology. Westropp’s essay argues that Phallic worship is “the most ancient of the superstitions of the human race” and goes on to demonstrate his point with wide reference to examples from around the world both in antiquity and in contemporary cultures. Westropp also argues that there are 3 stages in the representation of the phallus: firstly, as an “object of reverence and religious worship”; secondly, as a “protecting power against evil influences”; and thirdly, as “the result of mere licentiousness and dissolute morals.” Westropp’s essay, when first read to the ASL in April 1870, came in for some harsh criticism (which were not reproduced when the essay was published). According to one member, Westropp’s paper “does not seem to contain a single new fact, and repeats many errors already admitted to be errors.” This same critic cast doubt on Westropp’s assertion that Phallic worship was universal, stating that “A scientific paper should be something more than a string of assertions more or less discriminately collected.” 3

Wake, in his essay The Influence of the Phallic Idea in the Religions of Antiquity is more cautious in accepting the universality of phallic worship. Rather, he relates it to ideas about the family. Stating that “There must have been something more than a mere desire for progeny to lead primitive man to view the generative process with the peculiar feelings embodied in this superstition.” Wake sees the key to phallic worship, rather, in the veneration of the father, from which he asserts “has sprung the social organisation of all primitive peoples”. Thus he finds phallic significance in a wide variety of customs such as manhood initiation rituals, marriage, and circumcision. Drawing not only on antiquarian sources but also current anthropological reports (among them Burton) Wake carefully attempts to show the ubiquity of phallic themes lurking in both the ancient world and the contemporary customs of “primitive peoples”.

Wake’s essay also takes in serpent worship, the Mosaic account of the Fall, the relationship between Bacchus and Serpents and many examples of serpent worship across the world. Following these observations, He also examines phallic monuments such as the Greek Hermae and the Indian Linga, Sun Gods from around the world, and phallicism in Christian symbolism. He states for example: “There can be no question, however, that, whatever may be thought of its symbols, the fundamental basis of Christianity is more purely “phallic” than that of any other religion now existing.” Wake’s essay seems to have been less controversial when read at the ASL, although some of his etymological interpretations were judged to be faulty.

In the next post in this series, I will take a closer look at Edward Sellon’s “Annotations on the Sacred Writings of the Hindus”.

Sources

Sarah Bull Reading, Writing, and Publishing an Obscene Canon: The Archival Logic of the Secret Museum, c. 1860–c. 1900 (Book History, Volume 20, 2017, pp. 226-257).

Jocelyn Godwin The Theosophical Enlightenment (State University of New York Press, 1994)

Francis King Sexuality, Magic and Perversion (Citadel Press, 1974).

Jon Lange (ed.) Sellon’s Annotations: A Critical Edition (Self-Published, 2017 available from Amazon)

Deborah Lutz, Pleasure Bound: Victorian Sex Rebels and the New Eroticism (W.W. Norton & Company, 2011)

Andrew P. Lyons and Harriet D. Lyons Irregular Connections: A History of Anthropology and Sexuality (University of Nebraska Press 2004).

Memoirs Read Before the Anthropological Society of London 1863-4. (London. Trubner and Co. 1865)

Sellon, Edward. “[Comments on]: Linga Puja: On the Phallic Worship of India.” Journal of the Anthropological Society of London, vol. 3, 1865, pp. cxiv-cxxi.

JSTOR www.jstor.org/stable/3025310

Sellon, Edward. “[Comments on]: Some Remarks on Indian Gnosticism, or Sacti Puja, the Worship of the Female Power.” Journal of the Anthropological Society of London, vol. 4, 1866, pp. clxxxii-clxxxiii. JSTOR www.jstor.org/stable/3025399

C. Staniland Wake, The Influence of the Phallic Idea in the Religions of Antiquity The Journal of Anthropology Vol. 1, No. 2, (Oct. 1870) pp.199-227

JSTOR www.jstor.org/stable/3024834

Hodder M. Westropp On Phallic Worship Journal of the Anthropological Society of London, Vol. 8 (1870-1871), pp. cxxxvi-cxlvi.

JSTOR www.jstor.org/stable/3025178

Helen Wickstead Sex in the Secret Museum: Photographs from the British Museum’s Witt Scrapbooks (Photography & Culture Vol 0 Issue 0 2018 pp1-11)

One comment

Philip Grier

Posted March 20th 2021 at 12:07 pm | Permalink

Thank you for your article/paper. I was fortunate enough to study cultural anthropology and am happy to say the discipline is now free from moral judgement on the mythological practices of different peoples. We have come a long way but are not at the end yet.