Edward Sellon and the Cannibal Club: Anthropology Erotica Empire – II

Following on from the previous post in this series, I will now examine the activities of the Anthropological Society of London and its “inner cabal” – The Cannibal Club.

The Anthropological Society of London

The Ethnological Society of London (ESL) had been founded in 1843. It had emerged from the Aborigines Protection Society – social reformers who had provoked Britain to ban the slave trade in 1807 – and Christians who sought the uplift of “uncivilized tribes” via conversion and encouraged the collection of ethnographic data in order to shape enlightened policies. The Ethnological Society’s aim was to create a forum where scientists could investigate the habits and customs of different cultures, examine historical records, and debate theories of human origin.

The leading lights of the ESL tended to follow the biblical narrative that all of humanity had descended from Noah’s family and that they and other survivors of the Flood had dispersed to populate the globe. Any variations were products of circumstances – that racial variations resulted from different environments. This theory came to be known as Monogenism.

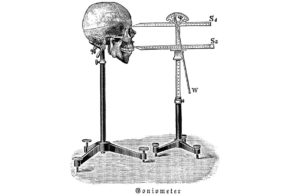

By the middle of the nineteenth century, a competing theory arose – that of Polygenism. The polygenists believed that humanity consisted of separate species. Race, for the polygenists, was not a feature of God’s will or a product of environmental differences, but biologically fixed and moreover, something which could be scientifically measured, using techniques such as craniotomy or anthropometry.

One of the staunchest proponents of polygenism was James Hunt (1833-1869). Initially, a member of the ESL, Hunt, together with Richard Burton, founded the rival Anthropological Society of London (ASL) in 1863. Burton shared Hunt’s polygenist views. Both men believed, for example, that Africans were racially inferior to Europeans, for example, and because of this, it was useless to try and “uplift” them via conversion to Christianity or education. They were opposed to the notion of the “civilizing mission” – the idea that the British presence in Africa or India was fundamentally a benevolent one, bringing progress or improvement to the uncivilized. 1

One of the staunchest proponents of polygenism was James Hunt (1833-1869). Initially, a member of the ESL, Hunt, together with Richard Burton, founded the rival Anthropological Society of London (ASL) in 1863. Burton shared Hunt’s polygenist views. Both men believed, for example, that Africans were racially inferior to Europeans, for example, and because of this, it was useless to try and “uplift” them via conversion to Christianity or education. They were opposed to the notion of the “civilizing mission” – the idea that the British presence in Africa or India was fundamentally a benevolent one, bringing progress or improvement to the uncivilized. 1

Both Hunt and Burton also chafed against the biblical doctrines of the ESL. Another key reason for the break was that the ESL had proposed to allow women to attend meetings, and both Hunt and Burton felt that the presence of women would prevent the free and frank discussion of sexual customs of the different races.

Hunt saw the task of the Anthropological Society was to bring together all related disciplines into a unified “Science of Man”. But he also saw the work of the Society as being of political significance. In his first address to the ASL, he stated:

“…do I exaggerate when I say that the fate of nations depends on a true appreciation of the science of anthropology? Are not the causes which have overthrown the greatest of nations to be resolved by the laws regulating the intermixture of the races of man? Does not the success of our colonization depend on the deductions of our science? Is not the composition of harmonious nations entirely a question of race? Is not the wicked war now going on in America caused by an ignorance of our science? These and a host of other questions must ultimately be resolved by inductive science.” 2

The Anthropological Society was less concerned with the history of humanity’s origins than with demonstrating and proving racial distinctions through techniques of measurement such as craniotomy. The human body became fixed and immutable – a more reliable source of evidence than confused and contested traveler’s accounts.

The Anthropological Society was less concerned with the history of humanity’s origins than with demonstrating and proving racial distinctions through techniques of measurement such as craniotomy. The human body became fixed and immutable – a more reliable source of evidence than confused and contested traveler’s accounts.

Within two years of its founding, the Anthropological had attracted over 500 members, sponsoring a vigorous programme of debates and lectures, and producing a steady stream of transactions and translations of anthropological works from European writers.

The Cannibal Club

The Cannibal Club was the “inner cabal” of the Anthropological Society, meeting at Bartolini’s dining rooms in London, this group of men met to drink, dine, discuss politics, religion and sexual customs, swap outrageous stories and indulge in what Burton called “orgies” – although not of the sexual kind.

Who were the members of the Cannibal Club? In addition to James Hunt and Richard Burton, some of the more well-known Cannibals included:

-

Charles Bradlaugh, Liberal MP, atheist, founder of the National Secular Society. (It was Bradlaugh who in 1877 was sent to trial along with Annie Besant for their distribution of a birth control manual, “The Fruits of Philosophy.”)

Conservative MP Richard Monckton Milnes, later Lord Haughton.

Colonel – later General – Studholme John Hodgson, military adviser to the Governor of Ceylon.

Charles Duncan Cameron, later British Consul in Ethiopia.

Decadent Poet and playwright – and all-round bad boy Algernon Swinbourne.

The bibliophile and noted collector of Erotica Henry Spencer Ashbee.

The painter Simeon Solomon whose promising career was cut short in 1873 when he was arrested for attempted Sodomy in a public convenience.

Foreign Correspondent for the Daily Telegraph, George Augustus Sala.

Pornographer and translator, James Campbell Reddie.

And of course, Edward Sellon.

The Cannibal’s symbol was a mace carved to resemble an African head chewing on a thigh bone. Swinbourne wrote a Cannibal Catechism:

“Preserve us from our enemies

Thou who art Lord of suns and skies

Whose meat and drink is flesh in pies

And blood in bowls!

Of thy sweet mercy, damn their eyes

And damn their souls.”

Sex Rebels

The Cannibals saw themselves as “sex rebels” and outsiders, and this is how they are sometimes treated by historians, but many of the Cannibals were members of the Establishment – members of parliament, diplomats, the legal profession, academia, and the Army. They had a wide range of influential contacts – both formal and informal – with respected bodies such as the Royal Geographical Society and the government. It was through these contacts that they were able to acquire some of the erotic literature that they prized. On one occasion, erotica from Europe was brought into Britain via a Foreign Office diplomatic bag containing dispatches for Lord Palmerston. This was arranged by Frederick Hankey, an ex-guards officer of sadistic tastes who, on one occasion, asked Richard Burton procure for him the skin of a young African woman which he could use to bind one of his volumes of erotica. Their “rebellion” was for the most part enacted within a privileged all-male homosocial space, free from the prying eyes of bodies such as the Society for the Suppression of Vice.

The MP Richard Monckton Milnes was known amongst his cannibal peers for having amassed one of the largest libraries of Erotica in Europe – so much so that his friends referred to his house as “Aphrodisiopolis”. Swinburne credited Milnes for having introduced him to the works of the Marquis de Sade. Another Cannibal, successful textile magnate and travel writer, Henry Spencer Ashbee, was probably the most dedicated erotic bibliophile of the period. Between 1877 and 1885 he produced three large bibliographies of “forbidden literature” written under the pseudonym of “Pisanus Fraxi”. He is also sometimes tagged as the author of the eleven-volume My Secret Life – one of the most famous works of Victorian erotic literature.

Some Cannibals held the view that erotic literature was a form of truth-telling; a form of anthropological reportage. The pleasure of reading about sex could then, be seen as a form of scientific investigation, and frankness about sexual matters was a mark of scholarly accuracy.

Ashbee for example writes:

“Erotic Novels … contain, at any rate the best of them, the truth, and “hold the mirror up to nature” more certainly than do those of any other description … [T]heir authors have, in most instances, been eyewitnesses of the scenes they have described … themselves enacted, in part, what they have portrayed. Immoral and amatory fiction … must unfortunately be acknowledged to contain … a reflection of the manners and vices of the times—of vices to be avoided, guarded against, reformed, but which unquestionably exist, and of which an exact estimate is needful to enable us to cope with them.” 3

The idea of the fictional erotic narrative as a “case study” is something that crops up later in the writings of early sexology.

A key figure in the erotic output of the Cannibals was James Campbell Reddie. Reddie was a skilled translator of Latin, Italian and French, and put his skills to work translating European and Classical texts for the obscene books trade, writing for The Exquisite, a risque journal published by one of Britain’s most notorious publishers of pornography – William Dugdale. Dugdale had a shop on Holywell Street – and later, on the Strand, where he sold both politically radical titles as well as works such as The Adventures of a Bedstead, The Mysteries of Whoredom, and the ever-popular Fanny Hill: The Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure. Dugdale died in prison in 1868, whilst serving two years hard labour for selling obscene material.

Reddie’s most famous work is The Amatory Experiences of a Surgeon. Some scholars have suggested that he co-authored, together with fellow Cannibal Simeon Solomon, Sins of the Cities of the Plains – Britain’s first exclusively homosexual pornographic novel, published in 1881. Sins is supposedly the memoirs of Jack Saul, a Mary-Anne or crossdressing male prostitute (a real person btw – he gave evidence during the trial following the 1889 Cleveland Street Scandal). Reddie was himself a homosexual and apparently made no secret of this to his fellow Cannibals. In a letter to Henry Spencer Ashbee in 1877, Reddie writes:

“There has also been the matter of a falling out with that damned dago who owned the house at Camden where I lived. I believe you met him on one of your visits to my rooms there. I will not weary you with the details; suffice it to say that my undoing may be laid to the credit of a weakness I conceived for the son of a Margate landlady at whose house I stayed for a few days last summer. Although an enthusiastic party to the proceedings himself, Pedroletti sought to extract money from me by threatening to inform the authorities.” 4

A letter purporting to be from Reddie’s Camden Landlord describing the goings-on in Margate in lurid and graphic detail appears in the November 1880 issue of The Pearl – the most famous of the Victorian erotic journals.

Reddie apparently knew all the major players in London’s smut trade, and he soon began bringing the writings of his fellow Cannibals to the attention of Dugdale. It is through Reddie that Edward Sellon began to publish obscene works for Dugdale.

Several of the Cannibals shared a taste for flagellation. For example, Daily Telegraph journalist George Augustus Sala, assisted by Reddie, wrote a flagellatory novel – The Mysteries of Verbena House, which was published in 1882 in a limited edition of 150 copies, priced at 4 guineas – a high price which effectively put it beyond the reach of working-class readers. MP Richard Monckton Milnes composed a poem extolling the delights of flagellation called The Rodiad, which was anonymously published in 1871. Colonel Studholme Hodgson was known amongst his cannibal peers as “Colonel Spanker” and later wrote under that sobriquet a book titled Experimental Lecture which was published in 1878 by William Lazenby.

For the most part, the Cannibals escaped prosecution under the Obscene Publications Act by publishing their erotic efforts anonymously, or as being “Privately Printed” – works which were circulated only to subscribers or amongst a clique of friends, rather than being sold over the counter. This restricted circulation was a way of getting around the Obscene Publications Act. Burton used this approach in his productions of the Kama Sutra and The Arabian Nights. In a letter to The Academy in 1885 concerning his translation of The Arabian Nights he writes:

“One of my principal objects in making the work so expensive [. . .] is to keep it from the general public. For this reason I have no publisher. The translation is printed by myself for the use of select personal friends; and nothing could be more repugnant to my feelings than the idea of a book of the kind being placed in a publisher’s hands, and sold over the counter.” 5

In the next post I will take a closer look at the life and works of Edward Sellon; libertine, atheist, orientalist, anthropologist, pornographer.

Sources

Sarah Bull Reading, Writing, and Publishing an Obscene Canon: The Archival Logic of the Secret Museum, c. 1860–c. 1900 (Book History, Volume 20, 2017, pp. 226-257).

Collette Colligan The Traffic in Obscenity from Byron to Beardsley: Sexuality and Exoticism in Nineteenth-Century Print Culture (Palgrave MacMillan, 2006).

Roberto C. Ferrari From Sodomite to Queer Icon: Simeon Solomon and the Evolution of Gay Studies (Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Spring 2001), pp. 11-13).

J Holmes Algernon Swinburne, Anthropologist (Journal of Literature and Science vol. 9, no. 1. 2016).

Patrick J. Kearney (ed.) Five Letters from James Campbell Reddie to Henry Spencer Ashbee (Scissors & Paste Bibliographies, 2019)

Dane Kennedy The Highly Civilized Man: Richard Burton and the Victorian World (Harvard University Press, 2005).

Deborah Lutz, Pleasure Bound: Victorian Sex Rebels and the New Eroticism (W.W. Norton & Company, 2011)

Andrew P. Lyons and Harriet D. Lyons Irregular Connections: A History of Anthropology and Sexuality (University of Nebraska Press 2004).

James McConnachie The Book of Love: In search of the Kamasutra (Atlantic Books, 2007)

Denise Merkle “Secret Literary Societies in Late Victorian England” in Maria Tymoczko (ed) Translation, Resistance, Activism (University of Massachusetts Press, 2010)

Catherine J. Rose A Secretly Sexualized Era: Pornography and Erotica in the 19th Century Anglo-American World (The Atlas: UBC Undergraduate Journal of World History |2005).

Vanita Seth Europe’s Indians: Producing Racial Difference, 1500-1900 (Duke University Press, 2010).

Lisa Z. Sigel Filth in the Wrong People’s Hands: Postcards and the Expansion of Pornography in Britain and the Atlantic World, 1880-1914 (Journal of Social History, Vol. 33, No. 4 (Summer, 2000), pp. 859-885).

Arno Sonderegger, “A One-Sided Controversy: James Hunt and Africanus Horton on The Negro’s Place in Nature” in Ulrich Pallua, Adrian Knapp and Andreas Exenberger (eds) (Re)Figuring Human Enslavement: Images of Power, Violence and Resistance (Innsbruck University Press, 2009)

George W. Stocking, Jr. Victorian Anthropology (The Free Press, 1987).

John Wallen The Cannibal Club and the Origins of 19th Century Racism and Pornography (The Victorian, Vol.1, Number 1, August 2013).

Online

William Dugdale A Checklist [By Title] of Works Published

Scissors & Paste Bibliographies

Notes: