Edward Sellon and the Cannibal Club: Anthropology Erotica Empire – I

I have for some time been interested in how representations of India – particularly those related to sexuality – emerged out of the Colonial period and went on to influence twentieth-century stereotypes of India in a wide variety of ways. The ready association made between Tantra and sex, for example, is something I would argue, has its roots in this period, as does much of the romanticism about India as a land of enlightened sexuality. It is this interest that led me into a murky territory which is sometimes called ethnopornography – a shadow zone where a piece of erotic writing can disguise itself as a scholarly work – or a scholarly work can be read as erotica. Where the body of the native is portrayed as alluring or threatening – sometimes both, and colonial territories become both zones of sexual adventure and hearts of darkness.

In investigating this territory I encountered Edward Sellon (see earlier posts) – a man who produced both anthropological papers and wrote pornography, some of which is set in India. Sellon is notable as he was one of the first Europeans to write approvingly of Tantra, and – and, portraying himself as an “expert” in Phallicism, helped to popularise the theory that all religions are rooted in fertility or Phallic Worship – a theory which was highly influential in cross-cultural anthropology, and became a key theme in the works of occultists such as Gerald Gardner, Dion Fortune, and Aleister Crowley, as well as both Freud, Jung, and early sexologists.

Sellon belonged to a dining club of elite influencers known as “the Cannibal Club” – an inner cabal of the Anthropological Society of London – a group of men who shared common interests – in politics, religion, and the investigation of the sexual customs of other countries and times. Many of them combined these interests with collecting – and producing – erotica.

In this series of posts (based on a lecture given at Treadwells Bookshop earlier this year) I will take a look at the circumstances that led to the formation of the Anthropological Society and the Cannibal Club and their interconnected activities. I will then go on to examine some aspects of Edward Sellon’s writing – his erotica, his anthropological essays, and his interest in Phallic religion, and close with some considerations for how to assess the influence of Sellon and his fellow cannibals. First though, some general background to the period.

Britain in the 1860s. The Engines of the Industrial Revolution run at full tilt. Britain produces a third of the world’s output of manufactured goods and two-thirds of the world’s output of coal. Britain, massing no more than 0.16% of the world’s landmass, rules much of India, Canada, Australia, Africa, Large chunks of Africa, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Gibraltar, several islands in the West Indies, and Ireland.

This is a period of great controversies. The literal interpretation of the Bible and biblical narratives of history is being questioned.

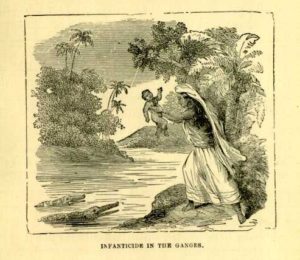

Matters of public health is also being debated such as the national birth rate, the breeding habits of the poor, infanticide and prostitution. Questions of education and in particular, moral guidance were being considered. It is also a period of rapid social and technological change.

the “Obscene”

The invention of the steam-powered printing press led to a rapid rise in the production of journals, newspapers and novels, and cheap pornography. Concerns over the rapid spread of cheap and available obscene literature and its effects on the morality of the lower classes led to the Obscene Publications Act of 1857. Lord Campell, who introduced this Act, famously commented that the ready availability of cheap obscene material was “the sale of a poison more deadly than prussic acid”. There was particular concern that London – the heart of the Empire – should have become such a centre of immorality.

How did the Victorians view pornography? Although the term pornography came into common usage in the 1860s, the most popular descriptive category was the “obscene” – and what counted as “obscene” was hotly debated. It could for example, include libel, and refer to politically inflammatory works too. Also included were medical works dealing with sexual matters, and books that described the sexual customs of foreign peoples. Lord Campbell’s view was his bill was “intended to apply exclusively to works written for the single purpose of corrupting the morals of youth and of a nature calculated to shock the common feelings of decency in any well-regulated mind.” The ensuing campaigns and legal actions in the wake of the Act tended to focus on the problem of obscene material almost entirely among the urban poor. There was a widespread view that those who were educated would be able to view obscene material without becoming morally corrupted.

The Act made publishers and authors cautious over what could be publically distributed and affected everything from illustrations of scientific textbooks to artistic portrayals of nudes. In 1870 for example, Henry Evans, a supplier of photographs of nude models to artists, was sentenced to two years hard labour despite a petition in his favour made by artists such as Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. This period in British history is often portrayed as one of general repression and prudery about sexual matters. The truth is rather more complex.

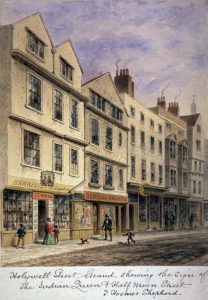

The trade in obscene material – books, prints, French snuffboxes, and playing cards was widespread. The foremost campaigning group – the Society for the Suppression of Vice – recorded that one of the most notorious areas in London for the trade – Holywell Street – had 57 bookshops selling obscene literature, until the Obscene Publications Act forced them to close down. There was also the so-called “sham indecent street trade” whereby street hawkers would loiter near the shops on Holywell Street, Wych Street (Holywell Street was demolished in 1902) and the Haymarket which displayed in their windows “shameless publications” for five shillings – and offer to sell these items for a mere sixpence or less in sealed packets, which turned out to be religious tracts, Christmas Carols or newspapers.

The trade in obscene material – books, prints, French snuffboxes, and playing cards was widespread. The foremost campaigning group – the Society for the Suppression of Vice – recorded that one of the most notorious areas in London for the trade – Holywell Street – had 57 bookshops selling obscene literature, until the Obscene Publications Act forced them to close down. There was also the so-called “sham indecent street trade” whereby street hawkers would loiter near the shops on Holywell Street, Wych Street (Holywell Street was demolished in 1902) and the Haymarket which displayed in their windows “shameless publications” for five shillings – and offer to sell these items for a mere sixpence or less in sealed packets, which turned out to be religious tracts, Christmas Carols or newspapers.

The Indian Mutiny

Another major event, of course, was the Indian Mutiny of 1857-1858, which sent shock waves throughout the Empire and led to something of a crisis of confidence. Whilst Indians were generally portrayed as religious fanatics attempting to overturn benevolent British rule, some commentators began to wonder if the immorality found in the metropole was somehow related.

One of the effects of the Indian Mutiny was an increased focus on the abhorrent practices of the natives which began as the Mutiny unfolded. As it took six weeks for letters to come from India to Britain, many newspapers printed lurid background stories about India, representing it as a mysterious and barbaric land, inhabited by fanatical religious devotees with obscene practices. As Francis Hutchins comments:

“Until 1857… India had seemed remote, its depravity little more than theoretical. At a stroke, the Mutiny made India both grimly real and relevant … and the English public followed with horrified fascination the unveiling of every minute detail of Indian perversity.” 1

The Mutiny also led to a shift in attitudes towards the natives of the colonies – and the development of new ideas about race. This brings us to the birth of the Anthropological Society of London and its inner circle, The Cannibal Club.

to be continued…

Sources

Francis G. Hutchins The Illusion of Permanence: British Imperialism in India (Princeton University Press, 1967)

Andrew C. Long Reading Arabia: British Orientalism in the Age of Mass Publication, 1880-1930 (Syracuse University Press, 2014)

Natalie Pryor The 1857 Obscene Publications Act: Debate, Definition and Dissemination, 1857-1868 (the University of Southampton Thesis for the degree of Master of Philosophy May 2014)

Notes:

- Hutchins, 1967 pp84-85 ↩