What Theosophy did for us – II: Places of Power – ii

Continuing from the previous post in this series which examined how Theosophical ideas about race reflected wider discourses of the period; I will now look in broad terms at the Theosophical Society’s relationship with Egypt, India and Tibet.

Egypt

Egypt has held a special place as the source of esoteric wisdom for centuries. According to Egyptologist Erik Hornung, the ‘mystification’ of Egypt began with Herotodus, and continued throughout the Hellenistic & Roman period, and onwards into the Hermetic renaissance and the birth of Rosicrucianism. A wide variety of esoteric subjects have been, at one time or another proclaimed to have had their roots in Egypt, including astrology, alchemy, Freemasonry, and tarot cards.

At the end of the eighteenth century, Napoleon Bonaparte’s Egyptian campaign ignited a vogue for Egyptian design in both France and Britain.

“Everything now must be Egyptian: the ladies wear crocodile ornaments, and you sit upon a sphinx in a room hung round with mummies, and with long black lean-armed long-nosed hieroglyphical men, who are enough to make the children afraid to go to bed.”

(Robert Southey, Letters from England 1807)

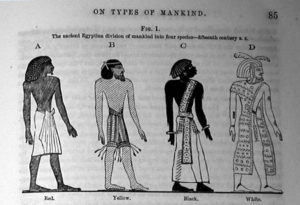

In the nineteenth century, the scientific investigation of Egypt in itself provided a challenge to religious literalism. The investigation of Egyptian monuments and artifacts began to indicate that human beings had been around for much longer than allowed for by Biblical chronology. At the same time, intellectuals in the nineteenth century began to question the “single origin” of humanity from the divine pair, Adam and Eve. As a way of justifying slavery, some scientists began to argue that races had separate origins, and occupied different places on the evolutionary ladder and that some of these races were inherently inferior – were not in fact ‘human’ and could be treated like animals. Egypt became central to these debates, as it was asserted that the evidence from ancient Egypt ‘disproved’ both the Biblical chronology and the Christian belief in the common origins of humanity. There also arose, from the work of Josiah Clark Nott (an American doctor and slave-owner); George Robbin Gliddon (a former vice-consul to Cairo) and the cataloguer of craniums Samuel Morton, a belief that the ancient Egyptians were neither Caucasian (as some of their contemporaries held) or Negroid in origin – that they were an ‘entirely separate’ race.

In the nineteenth century, the scientific investigation of Egypt in itself provided a challenge to religious literalism. The investigation of Egyptian monuments and artifacts began to indicate that human beings had been around for much longer than allowed for by Biblical chronology. At the same time, intellectuals in the nineteenth century began to question the “single origin” of humanity from the divine pair, Adam and Eve. As a way of justifying slavery, some scientists began to argue that races had separate origins, and occupied different places on the evolutionary ladder and that some of these races were inherently inferior – were not in fact ‘human’ and could be treated like animals. Egypt became central to these debates, as it was asserted that the evidence from ancient Egypt ‘disproved’ both the Biblical chronology and the Christian belief in the common origins of humanity. There also arose, from the work of Josiah Clark Nott (an American doctor and slave-owner); George Robbin Gliddon (a former vice-consul to Cairo) and the cataloguer of craniums Samuel Morton, a belief that the ancient Egyptians were neither Caucasian (as some of their contemporaries held) or Negroid in origin – that they were an ‘entirely separate’ race.

Egypt – as a site of origin for occult wisdom plays a key role in early Theosophical writings. In 1875, Blavatsky claimed that she was in contact with a group of masters – referred to as the “Brotherhood of Luxor” – something quite distinct, according to Blavatsky, to the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor.

In Isis Unveiled, Blavatsky dedicates an entire chapter to the discussion of Egyptian Wisdom. At the outset, she cites another author who has observed that the wisdom of Egypt is found at the very beginnings of that culture:

How came Egypt by her knowledge? … “Nothing,” remarks the same writer, whom we have elsewhere quoted, “proves that civilization and knowledge then rise and progress with her [with ancient Egypt] as in the case of other peoples, but everything seems to be referable, in the same perfection, to the earliest dates. That no nation knew as much as herself, is a fact demonstrated by history.”

She goes on to assert that:

“May we not assign as a reason for this remark the fact that until very recently nothing was known of Old India? That these two nations, India and Egypt, were akin? That they were the oldest in the group of nations; and that the Eastern Ethiopians – the mighty builders – had come from India as a matured people, bringing their civilization with them, and colonizing the perhaps unoccupied Egyptian territory?”

(Isis Unveiled vol. I p515)

The link between India and Egypt had already been a subject of intellectual debate. In 1813, the British ethnologist James C. Pritchard had published his Researches into the Physical History of Man, which asserted a connection between India and Egypt, not only culturally, but the idea that they were once ‘one people’.

Blavatsky in Egypt

Although a great deal of doubt has been cast – by historians at least – on the veracity of Blavatsky’s own accounts of her travels, there is, according to Jocelyn Godwin, an independent corroboration that Mme Blavatsky was indeed in Egypt in 1851, as witnessed by her long-time friend, the writer Albert Leighton Rawson, who visited Old Cairo with Blavatsky, where they learned the methods of the snake-charmers. According to Rawson, the two of them met a celebrated Coptic magician named Paulos Metamon. Rawson also recounts that an attempt was made to form a society for occult research, but that it failed.

Blavatsky apparently returned to Cairo in the early 1870s, and started a “Société Spirite” for the investigation of mediumship and related phenomena. By her own account, the aim was to demonstrate the differences between “passive mediums” and her own abilities as an “active doer”. She told A.P. Sinnett that the society foundered in two weeks because the hired mediums drank and cheated, and a madman with a gun disrupted the proceedings. So she dissolved the group and instead turned once more to her friend Metamon, of whom she said that the Egyptian high officials, whilst pretending to laugh at him behind his back, dreaded him and visited him secretly.

It’s possible, says Godwin, that “the Brotherhood of Luxor” is the coterie of esotericists that Blavatsky knew and worked within Egypt.

India

Whilst some orientalist scholars and missionaries tended to view the Brahmin elite of India as a priesthood keeping the great mass of the Indian populace enthralled in superstition (see for example William Ward) at the same time western romantics were busy hailing the profundity of their beliefs. In 1812, for example, Reuben Burrow published an article in the Journal of Asiatic Researches, asserting not only that Indians had a knowledge of algebra equal (if not greater than) leading western theorists, but that many Indian religious beliefs and concepts had directly influenced the West. In particular, he identified British druids with Indian Brahmins. A contemporary of Burrow, Thomas Morris, went even further in claiming that the Druids were direct descendants of a tribe of Brahmins. Geoffrey Higgins, in 1829, continued the equation of Brahmins and Druids by attempting to demonstrate that Druids were descendants of a so-called “first race” of people who had survived the Great Flood, finding sanctuary in the Himalayas. For Higgins, not only did Druids and Brahmins share a common religious outlook but, he felt it likely that they, together with the Magi of Persia would have kept in contact with each other.

Although Blavatsky had originally made Egypt to the preferred site for the roots of ancient wisdom, she quickly turned her gaze Eastwards, and in 1879 she and Colonel Olcott moved to India and subsequently established the Theosophical Society’s world headquarters in Adyar, Madras. They initially made contact with the Arya Samaj, led by Swami Dayananda Sarasvati. So impressed were Blavatsky and Olcott with Sarasvati that they had titled their nascent movement as “The Theosophical Society of the Arya Samaj of India”. Olcott had declared that Dayananda’s reformist agenda made him a modern Martin Luther, whilst Blavatsky stated that a member of the Himalayan brotherhood of adepts occupied Dayananda’s body and that he was, as such, to be regarded as a teacher guiding their work.

The Arya Samaj and Blavatsky, at least on the surface, had shared goals and interests. Blavatsky believed that the roots of the ancient wisdom that she was the torchbearer for, the ancient wisdom that lay behind all exoteric religion and that would in time, unite both science and religion, lay in India. Dayananda also believed in the supremacy of the Vedas, and that all forms of knowledge – both religious and scientific, could be found in them. However, he was highly critical not just of Christianity, as Blavatsky & Olctott, but of other Indian religions such as Jains or Buddhists. Cordial relations between the Theosophists and the Arya Samaj did not last long, and in 1881, Dayananda denounced Blavatsky and Olcott in a pamphlet entitled Humbuggery of the Theosophists. He accused Blavatsky and Olcott of being atheists, and proclaimed that Blavatsky had no real knowledge of, or interest in, the Vedas. However, by that time, Blavatsky and Olcott had gained more support in India and were no longer reliant on the Arya Samaj.

By 1884, barely five years after the Theosophical Society had established itself in India, it had over one hundred branches across the country. In 1885 the English Theosophist Alan Octavian Hume helped to establish the Indian National Congress (INC) and remained its general secretary for three decades. The records of the INC show a considerable overlap in membership that of the Theosophical Society in India, indicating that Theosophy had considerable appeal for young college-educated Indians who aspired to see India achieve greater political and cultural autonomy.

In the first post in this series, I mentioned the influence of Theosophy acknowledged by both Mohandas Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. Gandhi credits the influence of the Theosophical Society for kindling his interest in Indian philosophy when he had been, for a period, “affecting the English gentleman” in thought, dress and manners. Theosophy, admits Gandhi, inspired him to study Sanskrit and to learn by heart passages from the Bhagavad-Gita.

The involvement of the TS in Indian politics became more intense when Annie Besant was elected president of the Society. Whereas her predecessor, co-founder Colonel Henry Steel Olcott had advocated reform through education (and had created a network of Buddhist educational institutions in Sri Lanka, and in India created a Young Men’s Hindu Association and a Hindu Sunday-School Union). Annie Besant (who, as I noted in the previous lecture was something of a radical firebrand), founded the Home Rule League in India and became president of the INC. So vociferously did she agitate for Indian home rule in various Theosophical publications that she was jailed by the British authorities in 1917 – an act which had the consequence of making her a hero and a household name throughout India. This popularity was brief, however. When strikes that had been initiated by Gandhi led to riots in Delhi to which the British responded with using troops, killing a number of bystanders, Besant openly declared her support for the British, declaring:

The involvement of the TS in Indian politics became more intense when Annie Besant was elected president of the Society. Whereas her predecessor, co-founder Colonel Henry Steel Olcott had advocated reform through education (and had created a network of Buddhist educational institutions in Sri Lanka, and in India created a Young Men’s Hindu Association and a Hindu Sunday-School Union). Annie Besant (who, as I noted in the previous lecture was something of a radical firebrand), founded the Home Rule League in India and became president of the INC. So vociferously did she agitate for Indian home rule in various Theosophical publications that she was jailed by the British authorities in 1917 – an act which had the consequence of making her a hero and a household name throughout India. This popularity was brief, however. When strikes that had been initiated by Gandhi led to riots in Delhi to which the British responded with using troops, killing a number of bystanders, Besant openly declared her support for the British, declaring:

“A government’s first duty is to stop violence … Before a riot becomes unmanageable, brickbats must inevitably be answered by bullets in every civilized country.”

In the same month, April 1919, British Indian Army soldiers under the command of General Dyer opened fire (without warning) on a gathering of unarmed Sikhs in the town of Amritsar, killing several hundred people 1 and Besant’s slogan “brickbats and bullets” began to be used against her by her political opponents, and her endorsement of the British use of troops against demonstrators, in the aftermath of the Dyer massacre, saw her reputation in India irrevocably damaged.

Although Theosophy’s ideas and aspirations did have a special appeal in India – particularly western-educated Hindus who responded to its fascination with Asian values and its critique of western materialism – and that whilst both Gandhi and Nehru acknowledged that encountering the TS strengthened their sense of themselves as Indians rather than merely Imperial subjects, Theosophy was not without its Indian critics. The revivalist Swami Vivekananda dismissed Theosophy as:

“[an] Indian grafting of American Spiritualism with only a few Sanskrit words taking the place of Spiritualistic jargon – Mahatmic missals taking the place of ghostly raps and taps and Mahatmic inspiration that of obsession by ghosts …. Hindus have enough of religious teaching and teachers amidst themselves even in the Kali-Yuga, and they do not stand in need of dead ghosts of Russians and Americans.”

A radical member of the INC, Gangadur Bal Tilak described his difficulties with Annie Besant:

“I cannot bear for a moment the supremacy which she claims for her opinions in matters political under the guise that she is inspired by the Great Souls and that such orders as she professes to receive must be unquestionably obeyed … Congress recognizes no Mahatma to rule over it except the Mahatma of majority.”

In spite of the Theosophists’ sincerity in advocating Indian home rule or establishing colleges and schools, it was their over-emphasis on arcane knowledge and the reliance of ‘astral communications’ with masters that became its greatest weakness.

Tibet

Blavatsky first encountered the great soul known to her as the Master Morya in England in 1851. By Blavatsky’s own accounts, she made her first – unsuccessful – attempts to enter Tibet in 1856 & 1857. In 1867, whilst she was in Florence, recovering from a wound received at the battle of Mentana, where she fought with Garibaldi’s army, she was contacted by the Master Morya – a master of the Tibetan Brotherhood, who ordered her to go to Tibet for occult training. Blavatsky spent two years with Morya’s colleague Koot Hoomi.

In this period, Tibet remained to a large extent, an unknown and mysterious country. Most of what was known about Tibet was culled from the accounts of travelers, which literary figures drew upon, in order to emphasize the magical and romantic landscape. As with India, Tibet was seen to be simultaneously representing a ‘golden past’ of wisdom which, by the time Europeans arrived, had degenerated. Late Nineteenth-century accounts of the Tibetan people describe them in conflicting ways – cowardly and courageous, gentle and aggressive. Henry Savage Landor, for example, describes them as a “miserable lot” and asserted that he could sort out any problems with the natives with “a good pounding with the butt of my Mannlicher [rifle].”

L. Austin Waddell, who accompanied the 1904 Younghusband expedition to Tibet, summed up the Tibetan religious works he encountered:

“Books now abound in Tibet, and nearly all are religious. The literature, however, is, for the most part, a dreary wilderness of words and antiquated rubbish, but the Lamas conceitedly believe that all knowledge is locked up in their musty classics, outside which nothing is worthy of serious notice.”

Again, as with India, orientalists approached Tibet with a condescending attitude to the natives and a conviction that only educated westerners could peel away the ‘superstition’ that surrounded Tibetan Buddhism. In the literature of the period, Buddhism – particularly Tibetan Buddhism, was often related to Catholicism.

Theosophy’s legacies: Shamballa and Shangri-La

Poul Penderson 2 points out that whilst Blavatsky claimed to be a Tibetan Buddhist, it is striking that only two of her masters were Tibetans and there were no actual Tibetans in the Theosophical Society. But then, he admits, there were no Tibetans on the global religious & esoteric scene in which the Theosophists were acting. Tibet and the Tibetan people, says Penderson, were for the Theosophists, purely imaginary objects, made up from various sources such as scholarly works on Buddhism, esoteric books and travelogues. However, Penderson goes on to say that Blavatsky was, in many ways responsible for the appearance of Tibetan “spiritual masters” into the west a century later.

Why was Tibet important as a ‘sacred space’? Tibet was geographically close to India but was perceived as isolated and inaccessible – features which enhanced its aura of mystery. Frank J. Korom, in an essay examining the role of Tibet in the New Age Movement, recounts an encounter with a New Age practitioner, who told him that the need for a real Tibet is secondary to the “astral” Tibet, since it is the ethereal plane where the masters reside.

Theosophy’s influence on Buddhism

Although the Theosophical Society did much to strengthen western interest in Asian philosophy and religion, what is more important, says Penderson, is their introduction of western interpretations of those traditions to educated Asian elites.

Although the Theosophical Society did much to strengthen western interest in Asian philosophy and religion, what is more important, says Penderson, is their introduction of western interpretations of those traditions to educated Asian elites.

One significant example of this process, according to Penderson, is the increasing tendency to psychologize Buddhism. Whilst in the nineteenth century, there was a good deal of debate amongst scholars over whether or not Buddhism was a religion or a philosophy, a number of contemporary exponents of Buddhism have asserted that Buddhism finds more in common with western notions of transpersonal psychology rather than theology. Penderson points out that increasingly, western conceptions of Buddhism are being framed within a discourse that emphasizes mental hygiene rather than salvation. Blavatsky’s influence on this process is in her teachings, which exalt an idealized East in order to castigate the materialist West (in a similar manner to the Romantics and Idealists of the period) and that the East has access to an esoteric wisdom that the West has, for the most part, lost. Theosophy brought Buddhism, Tibet and Psychology (and I noted in the first post that HPB’s notion of “spiritual psychology” distinct from mere materialist science) together in its popular esoteric discourse, and the dissemination of these ideas, through its immense publishing machine, played a crucial role in the popular imagining of Tibet. This process of psychologization was also furthered by Jung in the 1930s. Jung wrote introductions for books which have come to be highly influential in the west, such as Walter Evans-Wentz’s Tibetan Book of the Dead (of which more later) and Suzuki’s popular Introduction to Zen Buddhism. Jung continually reiterated his belief that the “oriental” religions provided profound insights into the workings of the psyche, with the consequence that, for Jung, several Asian religious concepts – such as the chakras for example – were reinterpreted solely as techniques for psychological health. The notion that the East could offer healing remedies to counter the ‘sickness’ of western civilization became a popular feature in the 1960s counterculture.

A key element in the psychologization of Buddhism is Walter Evans-Wentz’s 1927 production of The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Evans-Wentz was a theosophist, and his production of the “Bardo Thol” is heavily influenced by the writings of Blavatsky, according to scholar Donald Lopez, who points out that Evans-Wentz’s believed that both Tibet’s Buddhist culture and Egypt had a common origin – in Atlantis.

Evans-Wentz presents a doctrine of rebirth (which he declares to be the central principle of the Book of the Dead) in light of a semi-Darwinian theory of biological evolution. He argues against Buddhist doctrine and argues that humans can only be reincarnated as humans, and animals only as animals – this he claims, is the “true” or esoteric meaning of Buddhism. He further asserts that it is only the “esoteric” layer of Buddhism that carries a universal truth – mere exoteric Buddhism is mistaken and irrational. Once again this reflects a dominant belief in the 19th century – that of cultural corruption – that pristine religious truths have become, over time, corrupted so that the truth is hidden. Evans-Wentz, in his translation of the Book of the Dead, is concerned with the primary task of revealing the ‘truth’ of the texts (in much the same way that Max Muller is with the Vedas) although his particular truth is the ‘esoteric’.

In the next post in this series I will turn my attention to the Theosophical mapping of “inner space” with a look at the work of Annie Besant and Charles Webster Leadbeater’s works on Thought-Forms and the Astral Plane.

Sources

Bishop, Peter, Dreams of Power: Tibetan Buddhism and the Western Imagination The Athlone Press, 1993

Dodin, Thierry & Rather, Heinz (eds), Imagining Tibet, Perceptions, Projections, Fantasies, Wisdom Publications, 2001

Faivre, Atoine & Needleman, Jacob (eds) Modern Esoteric Spirituality, SCM Press, 1993

Godwin, Jocelyn, The Theosophical Enlightenment, SUNY, 1994

Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (ed), Helena Blavatsky, North Atlantic Books, 2004

Hornung, Erik, The Secret Lore of Egypt: It’s Impact on the West, Cornell University Press, 2001

King, Richard, Orientalism and Religion: Postcolonial Theory, India and the Mystic East, Routledge, 1999

Noll, Richard, The Jung Cult: Origins of a Charismatic Movement, Princeton University Press, 1994

Owen, Alex, The Darkened Room: Women, Power, and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England, University of Chicago Press, 1989

Owen, Alex, The Place of Enchantment, British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern, University of Chicago Press, 2004

Ryan, Charles. J, H.P. Blavatsky and the Theosophical Movement, Theosophical University Press, 1975

Sugirtharajah, Sharada, Imagining Hinduism, A Postcolonial Perspective, Routledge, 2003

Tillett, Gregory, The Elder Brother: A biography of Charles Webster Leadbeater, RKP, 1982

Wilson, A.N., The Victorians, Arrow Books, 2003

Notes:

- In 1997, the Duke of Edinburgh, participating in an already controversial British visit to the Amritsar monument, provoked considerable outrage in India and in the UK with an offhand comment. Having observed a plaque claiming 2,000 casualties, Prince Philip observed, “That’s not right. The number is less.” ↩

- see Tibet, Theosophy and the Psychologization of Buddhism, in Thierry & Heinz (eds) 2003 ↩