The Puzzle of the Pasupati Seal

Back in 2020, I briefly discussed the notion sometimes encountered that Tantra is thousands of years old – that it predates the Vedas, Buddhism, and Jainism. To illustrate the post, I used an image of the infamous Pasupati Seal that is often pointed to as evidence of Tantra’s antediluvian origins. So for this post, I’m going to take a closer look at the Seal and its tangle of interpretations.

The cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-Dara, ruins of what is now known as the Indus Valley Civilization were uncovered in the first decades of the nineteenth century, although their significance was not realized for almost a century. In 1856, British engineers used bricks from Harappa for building a railway line between Karachi and Lahore. In 1912, a series of seals bearing previously unknown symbols were discovered by J. Fleet. This led to an excavation of the sites between 1921-22 by Sir John Marshall, Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India from 1902 to 1928.

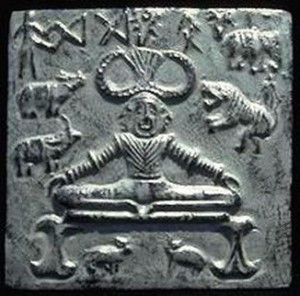

One of the Seals unearthed by Marshall’s expedition is the famous “Pasupati Seal”. It is 3.6×3.5cm, 0.7cm thick, and made of steatite. In his 1937-38 report, Ernest Mackay dated the seal from 2,350-2,000 BCE. Here’s Sir John Marshall’s description of the Seal, from his 1931 work, Mohenjo-daro and the Indus civilization:

“He is striking portrayed on the roughly carved seal … which has recently been brought to light by Mr. Mackay. The God, who is three-faced, is seated on a low Indian throne in a typical attitude of Yoga, with legs bent double beneath him, heel to heel, and toes turned downwards. His arms are outstretched, his hands, with thumbs to front, resting on his knees: From wrist to shoulder the arms are covered with bangles, eight smaller and three larger ; over his breast is a triangular pectoral or perhaps a series of necklaces or torques, like those on the later class of Goddess figurines from Baluchistan; and round his waist a double band. The lower limbs are bare and the phallus (urdhvamedhra) seemingly exposed, but it is possible that what appears to be the phallus is in reality the end of the waistband. Crowning his head is a pair of horns meeting in a tall headdress. To either side of the god are four animals, an elephant and tiger on his proper right, a rhinoceros and buffalo on his left. Beneath the throne are two deer standing with heads regardant and horns turned to the centre. At the top of the seal is an inscription of seven letters, the last of which, for lack of room at the right-hand top corner, has been placed between the elephant and the tiger.”

John Marshall, Mohenjo-daro and the Indus civilization, Arthur Probsthain 1931 p52

Marshall goes on to give his reasons for identifying the seal as a representation of Śiva. Firstly, He points out that the figure is three-faced, and that Śiva, in later times, is depicted as having up to five faces, and always, three-eyed. He also speculates that the figure may be a representation – a presentiment perhaps, of the trinity of Śiva, Brahma, and Vishnu. Secondly, he discusses that this “pre-Aryan god” is seated in a yoga position, and points to Śiva’s strong associations with Yoga. He writes:

“Primarily, the purpose of Yoga was the attainment of union (yoga) with the god by mental discipline and concentration: but it was also the means of acquiring magical powers, and hence in course of time the yogi came to be regarded as a magician, miracle-worker and charlatan. Like Saivism itself, yoga had its origin in among the Pre-Aryan population, and this explains why it was not until the Epic Period that it came to play and important role in the Indo-Aryan religion.”

Marshall, 1931, p54

Marshall’s third proof is that Śiva is not only the prince of Yogis; he is also “lord of the beasts (pasupati)”. He points out that in “Historic times” pasupati is an epithet applied to Śiva, and to the Vedic deity Rudra, and that the cult of Rudra was amalgamated with Śiva – possibly due to this common identification. He makes a comparison between the figure on the seal surrounded by animals and the “nameless God and Goddess of Minoan Crete” and Cybele, whom he asserts is analogous to the Mahadevi.

Next, he turns his attention to the figure’s horns. He asserts that the horns have sacred significance, although he admits that this “does not amount to actual evidence of identity” but goes on to suggest that in later times, the horns became the trisula (trident) emblem of Śiva. In summarizing his argument, Marshall states:

“we shall probably not be far wrong if we infer that this pre-Aryan deity, who so closely resembled Śiva in other fundamental respects, resembled him also as a god of destruction and terror, to be propitiated by human or other bloody sacrifices, and as chief of mischievous spirits, demons, and vampires.”

Marshall, 1931, p56

The notion that Śiva was of non-Aryan origins was, by the time that Marshall and his colleagues unearthed the Pasupati Seal, a commonplace of orientalist thought. In 1846 for example, John Stevenson, in a paper entitled The Ante-Brahmanical Religion of the Hindus 1 argued that Śiva was worshipped by the “aboriginal Indians” and later incorporated into the Brahmanical religion. He proposes that Śiva was originally known as Kedár, the name of a Himalayan peak. Gustav Oppert, in his 1893 book On the original inhabitants of Bharatavarsa or India proposed the existence of a pre-Aryan/Semitic race called the Bharatas, a branch of the Finnish-Hungarian race. The Bharatas, according to Oppert, were inferior to the Aryans because they worshipped a matriarchal deity, and that they lacked a capacity for abstract thought. Oppert cites Stevenson in arguing that the worship of Śiva – and in particular, the worship of the Linga, is non-Aryan in origin. He also states that the worship of Śiva is more prevalent in the South and East of India than the North, and that Brahmans do not officiate in Linga temples. Rather, Linga temple officiants are a distinct caste, originally of Sudra origin. Oppert also argues that the veneration of goddesses is of pre-Aryan origin.

The very notion of a pre-Aryan civilization is rooted in the concept of the Aryan Invasion Theory (AIT). The short summary of this theory is that sometime around 1500 BCE, an aggressive race of Sanskrit-speaking nomads invaded the Indian subcontinent, destroying the Indus Valley civilization, and subduing the indigenous inhabitants, driving them into South India, where they became the “Dravidians”. This is often treated as a done deal – a historical fact, but in actuality, this is far from the case. I’ve been examining some aspects of the Aryan issue in my series on Theosophy and Race, and I will leave a critical examination of the AIT for another time. Suffice it to say, the theory has become highly politicized and controversial due to its association with nineteenth-century racial theories, colonialism, and the general lack of any conclusive evidence to support it.

The Problem of the Pasupati Seal

Although Marshall’s identification of the Seal is popular and widely cited, it has been subjected to several critiques by scholars. B.A. Saletore, in a 1939 paper 2 pointed out the difficulties in assigning later ideas to a prehistoric seal. He proposed that the figure had three faces and a headress of three horns. He related these attributed to the Vedic deity Agni, who has three heads, and whose flames are his horns. N. Chaudhuri 3 pointed out that the features Marshall uses to prove that the seal represents a proto-Śiva are not associated with Śiva until the period of the Epics and the Puranas. He is equally doubtful of Marshall’s idea that the horned headgear could evolve into a trident. H.P. Sullivan 4 argues that the figure on the seal is, in fact, a mother-goddess.

Doris Srinivasan 5 makes the case that the figure is a divine buffalo-man. She points out that the phallic nature of the figure is tentative – as Marshall himself admitted, and that thus far, there have been no other figures recovered from Mohenjo-Daro or other Indus Valley sites that have erect phalluses. Most recently, Alf Hiltebeital 6 has proposed that the Seal represents the buffalo-demon Mahishasura.

In short, no one is really sure what the Seal represents, although many speculative theories have been offered. Many explanations for the Seal rest on interpretations that “read” it in terms of later practices. There is no conclusive evidence in any of the Indus Valley artifacts that conclusively support the notion that either Tantra or Yoga originated in prehistory.

As to whether or not Śiva’s origins are from a Vedic or non-Vedic background, the question remains open. There is still debate about Rudra – often thought to be Śiva’s predecessor in the Vedas – and his role within the Vedic pantheon. Only three of the 1,028 hymns in the Ṛgveda are exclusively directed at Rudra, and seem to indicate that as a deity, Rudra is both benevolent (healing) and malevolent. Many of the names he is given in early sources – Śarva, Ugra, and Mahādeva, for example, do become epithets of Śiva. The first time that a full-blown theology of Rudra as an all-pervasive deity appears is in the Śvetāśtaropaniṣad, where he is regarded as the supreme lord and the only deity capable of granting liberation to his devotees. Rudra is also identified with Śiva several times within this text.

Further Reading

For a comprehensive review of the Aryan Invasion Theory debate, I’d recommend Edwin Bryant’s The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate (Oxford University Press, 2001) and also Nayanjot Lahiri’s edited collection of essays, The Decline and Fall of the Indus Civilisation, Permanent Black, 2000. Geoffrey Samuel’s The Origins of Yoga and Tantra: Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century (Cambridge University Press, 2008) is also recommended.

Notes:

- The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 8 (1846) ↩

- “Identification of a Mohenjo Daro Figure,” The New Review, X (July-December 1939, pp28-35. ↩

- “Indus People and the Indus Religion I“, The Calcutta Review (July-Dec 1952) pp75-90 ↩

- “A Re-examination of the Religion of the Indus Civilization,” History of Religions, IV (1964) pp.115-125 ↩

- “The So-Called Proto-śiva Seal from Mohenjo-Daro: An Iconological Assessment,” Archives of Asian Art, Vol. 29 (1975/76), pp47-58 ↩

- “The Indus Valley “Proto-Śiva”, Reexamined through Reflections on the Goddess, the Buffalo, and the Symbolism of vahanas”. In, Adluri, Vishwa, Bagchee, Joydeep (eds.) When the Goddess was a Woman: Mahabharata Ethnographies – Essays by Alf Hiltebeitel. Brill, 2011. ↩