Tantric Subtle Bodies – I

As a spin-off from the last couple of posts outlining tantric ritual procedures, I thought I’d turn to a more complex issue and tackle the concept of the ‘subtle body’ and how it is used in tantric practice. The term ‘subtle body’ is immediately familiar of course – it has a long history of usage in Western esotericism, from Aristotle to Aleister Crowley and beyond. Sanskrit terms such as lingaśarīra, sūkṣmadeha or sūkṣmaśarīra– often used to refer to the subtle body – was popularized in Western esotericism by the writings of H.P. Blavatsky and other Theosophists, drawing heavily on the work of Henry Thomas Colebrooke and Max Muller. André Padoux points out that this conflation of terms is a misnomer, as the sūkṣmadeha or sūkṣmaśarīra, in actuality, refers to that entity that migrates from body to body after death and lacks any shape, visualized components or affective qualities.

For this first post, I’m going to outline the structure of the subtle body as given in verses 1-2, Netra Tantra, Chapter 7.

The Netratantra (‘Tantra of the [third] Eye [of Śiva]) is a voluminous work that has received much attention from scholars. Alexis Sanderson has dated its origin to between 700-850 C.E. Whilst it contains much that is of interest regarding tantric yoga, its primary interest is that of Śaiva officiants in the service of a king, and there are many procedures detailed for the protection, both of a royal family and an entire kingdom. There is an important commentary on this scripture by Kṣemarāra, the principal disciple of Abhinavagupta. It is classed as one of the Bhairava tantras, occupying a point within the spectrum of tantric traditions between the mainstream Śaiva Siddhānta and the more heterodox movements.

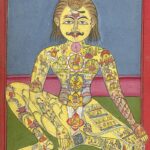

The subtle body is detailed in Chapter VII of Netratantra, with the term Sūkṣma-dhyāna. It begins by enumerating the constituents of this body: six cakras, sixteen ādhāra (‘supports’), three lakṣya (‘goals’), five vyoma (‘voids’), twelve granthi (‘knots’), three dhāman (‘luminaries’), and three, ten, and 72,000 nāḍi (‘channels’). The subtle body is to be envisioned as a vertical axis linked together by a complex series of channels. Also important are the three śaktis – icchaśākti (‘will’), jñānaśākti (‘cognition’) and kriyāśākti (‘action’).

The six cakras, as named by Kṣemarāra are nāḍi, the ‘birth’ channel at the place of the sexual organ; māyā, at the navel; yoga, at the heart, bhedana, at the palate; dīpti, at the point between the eyebrows, and nāda, at the forehead.

Closely related to the cakras are the sixteen ādhāra (‘supports’). They are located at the big toe, ankle, knee, sexual organ, anus, the kanda (‘bulb’), the nāḍi (‘channel’), stomach, heart, kūrmanāḍī (‘tortoise channel’), throat, palate, between the eyes, forehead, aperture of Brahma, and the dvādaśānta (place of twelve fingers, i.e. ‘twelve fingers’ above the crown of the head).

The three lakṣya (‘goals’) are foci for drawing the yogin onwards in practice. They are destinations upon which the practitioner must fix their attention.

What of the five vyoma (‘voids’)? Kṣemarāra locates them as parallels to the cakras and ādhāras: at the points of birth, navel, heart, bindu (i.e. between the eyes), and nāda. Bettina Bäumer, in her introduction to Chapter VII of Netratantra, explains how these voids relate to the nature of Śiva as experienced at different stages of yogic ascent.

Now to the twelve granthi. Kṣemarāra names them as: māyā, pāśava (at the sexual organ), Brahmā (heart), Viṣṇu (throat), Rudra (palate), Īśvara (between the eyes), Sadäśiva (forehead), indhikä, dīpikā, baindava, nāda, and śakti.

Brahmā, Viṣṇu, etc., are the kāraṇa-devatās or ‘cause-deities’ that preside over the cakras in tantric yoga, given in order of ascension. The kāraṇa-devatās change according to particular lineages – for example, sometimes Ganeṣa, or Indra, are assigned to the lowest cakra in a schema. All of the kāraṇa-devatās are deities associated with lordship or creation. Īśvara can simply be translated as ‘the lord’. Sadäśiva – ‘eternal Śiva’ is the highest form of Śiva according to the Śaiva Siddhānta tradition. As part of the practitioners’ ascent through the tantric body, these deities and their powers are accessed, but ultimately to be transcended. Note that the highest form of deity in the Netratantra is Amṛteśvara, together with his consort, Amṛteśvarī. The Netratantra says that Amṛteśvara can be worshipped in the form of any other aspects of Śiva, but also, Viṣṇu, Sūrya, Brahmā, Gaṇeśa, and the Buddha.

The first granthi, māyā, is the mahāgranthi, from which all other obstructions emerge (i.e. māyā-tattva). It is located at the place of ‘birth’ i.e. the generative organ.

The three dhāman are the sun, moon, and fire, homologized with the three central channels; sun – piṅgalā; moon – iḍā, and fire – suṣumnā.

Sources

Bäumer, Bettina Sharada. 2021. The Yoga of Netra Tantra: Third Eye and Overcoming Death. New Delhi. D.K. Printworld.

Cox, Simon. 2022. The Subtle Body: A Genealogy. New York. Oxford University Press.

Padoux, André. 2017. The Hindu Tantric World: An Overview. Chicago and London. University of Chicago Press.

Pati, George, and Zubko, Catherine C. (eds). 2020. Transformational Embodiment in Asian Religions: Subtle Bodies, Spatial Bodies. London and New York. Routledge.

Sanderson, Alexis. 2004. ‘Religion and the State: Śaiva Officiants in the territory of the king’s Brahmanical Chaplain’. Indo-Iranial Journal, Vol.47, No. 3-4, pp229-300.

Southoff, Patricia. 2022. Illness and Immortality: Mantra, Maṇḍala, and Meditation in the Netra Tantra. New York. Oxford University Press.