On Reading Occult Books

“Few people ask from books what books can give us. Most commonly we come to books with blurred and divided minds, asking of fiction that it shall be true, of poetry that it shall be false, of biography that it shall be flattering, of history that it shall enforce our own prejudices.

Virginia Woolf, “How one should read a book”, The Second Common Reader, 1925.

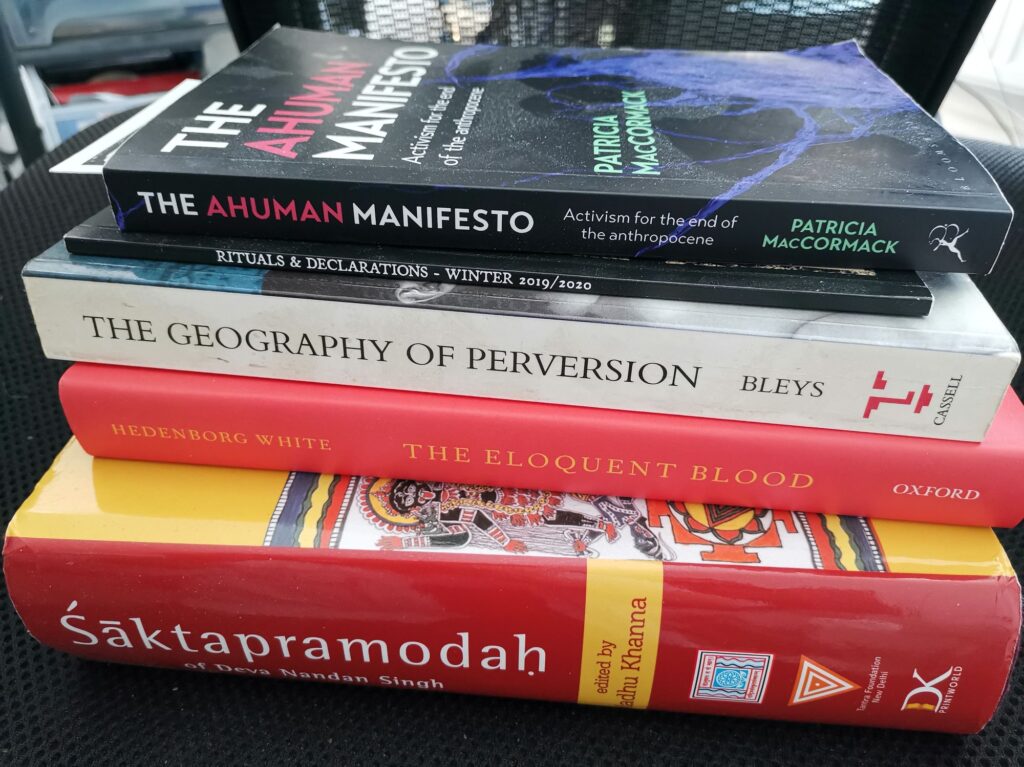

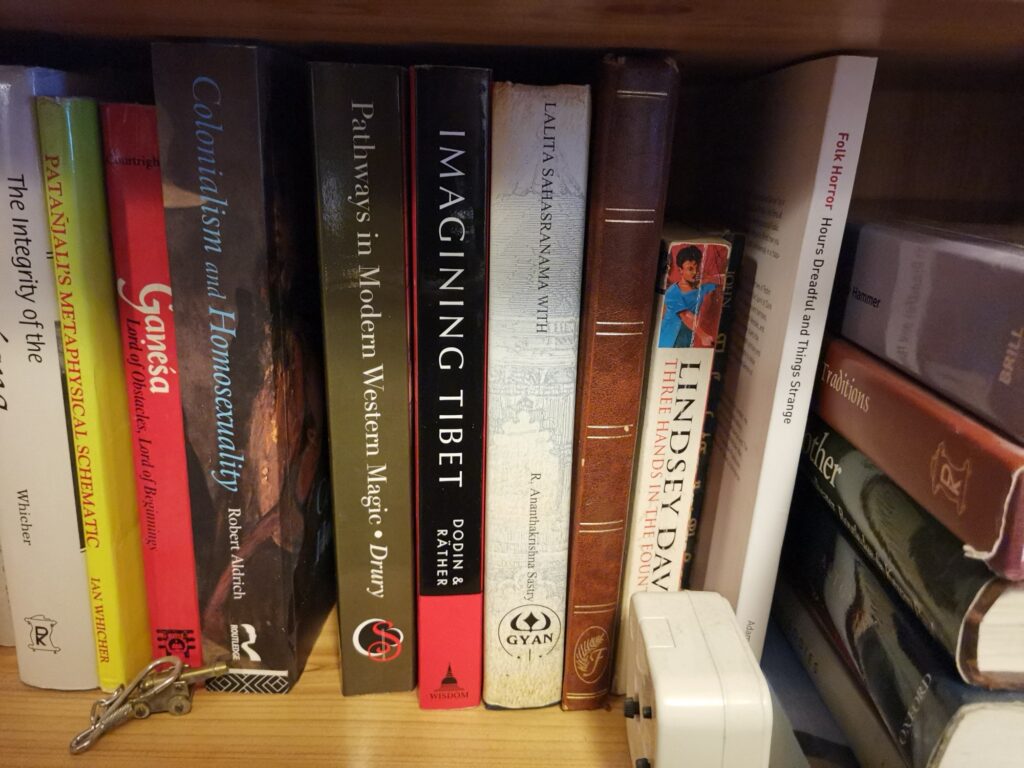

How do we go about reading an occult book? It seems like an obvious question to ask, but thus far, I have yet to see any attempt to explore this issue in any depth. This is strange, given how much occult books are part of contemporary occult practice. The effort and expense we go to acquire them, how we cherish them, and how books influence our trajectories and shape our ideas.

I can only offer my own thoughts on the matter, arising out of my own experience of reading occult books over the last 40 years or so.

When we first open ourselves to the world of the occult, it is all terribly exciting and new. At least that was my experience, and other people I’ve talked to over the years agree. I rushed to my local library and hungrily devoured anything I could find. Spiritualism, novels (Dennis Wheatley mostly), and the works of Theosophical authors such as H.P. Blavatsky and Alexandra David-Neel.

It is as though a hungry person is presented with a large plate of, let’s say mashed potatoes and peas. So hungry they gobble it down so fast they might not notice any subtleties in the food – say a pea that is particularly hard or one that is a bit sour. That’s how I think of it.

A couple of years later after beginning my dive into occultism I went off to pursue a degree course in another part of the country. It was a great course for me. I spent three years imbibing Psychology – studying every aspect of that discipline from the works of Freud to how to perform an experiment. In addition, there was Sociology, Social Policy, Statistical analysis, and Philosophy too. More importantly for me at the time though, I met for the first time other occultists, began my first tentative explorations of ritual and practice, began to know myself, and become something other than I had been. But along the way, I was taught some elements of critical reading. How to analyze what an author is saying; how to compare ideas; how to go about researching books and articles; how to construct an essay.

But – and here’s the rub – I did not apply those critical reading skills to the occult books I was reading. At least not yet. On reflection, that is, I feel understandable. I was still at the stage when I was too busy reading everything I could get my hands on regarding the occult to actually stop long enough to think critically about what I was reading. It was as though it was in a separate domain to the rest of my life, shielded from the critical attention I might pay to take apart a psychology paper or a piece of social legislation, teasing out the weaknesses of an argument or dubious assertions made on the basis of paper-thin evidence.

I had, at that point in my life, met comparatively few other people with whom I could discuss a particular occult concept or idea. Some of the occult practitioners seemed to accept everything they’d read in books as entirely factual – as truths as inviolable and obvious as we might find in any school textbook. As true as two plus two equals four. Why question that?

Occult authors do have a tendency to view their own ideas and opinions as though they were cosmic laws, delivered steaming, still shedding ice, from some Platonic realm of pureness. Until we learn otherwise, it is very easy to go along with this. After all, who are we, mere beginners along the path to question the words of a great and wise adept or Spiritual Master? It is a matter of confidence, I feel. If we don’t feel confident, as we move into a new territory of thought and action, it’s often difficult to admit that we have reservations and counter-opinions. In those early years, I read a great deal and probably understood – in the sense of actually mulling ideas over – very little of it. But at the same time, I absorbed a great deal of information without actually realizing it and just accepted it at face value. I neither questioned what I was reading, nor did I try and pick holes in a statement about the nature of reality, or whether what was being presented as unvarnished and platonic truth was actually an opinion, and where that opinion might have come from.

Therein lies the danger. What can I possibly mean by “danger”? One day, I was idly skimming through a book devoted to explaining the Qabalah – its principles, its symbols – its occult truths, if you like, when a statement suddenly caught my entire attention.

“homosexuality, like drugs, is a technique of black magic … In spite of the modern state of apologetics for this form of lower emotional and physical relationship it is a perversion and evil”. 1

Now at this time, I was not very far along in the process of discovering my own sexual feelings. I knew that I was sexually attracted to both women and men, but I was having a hard time coming to terms with that. “homosexuality, like drugs…” Well, I’d already tried drugs of various kinds, but was I really condemned to be damned as evil – a black magician no less – just because I fancied other men?

It seemed to me that here was an example of an “occult truth” – delivered without any equivocation or room for debate – which I simply could not accept as legitimate. At least not at first. I did speak to some other occultists I knew about this – carefully, as I did not want to ‘out’ myself to them; and one, who at the time I respected greatly did say that if someone is gay or bisexual then the ‘occult path’ is closed to them. Something to do with polarity, I forget exactly. So I remained confused, and perhaps a little bit heartbroken for a while, and then just decided that I wasn’t going to accept this. More importantly, I became angry, and I started to wonder just how many other occult statements of ‘truth’ or so-called cosmic laws were in actuality rooted in prejudice, or based on unthinking assumptions, faulty logic, or what we now call “alternative facts”.

Some books do make us angry, and I think this is valuable. Some books I have hung onto for years, and still read, not because I enjoy them particularly, but the anger I feel when reading them can be a source of inspiration, a desire to do better. One of the reasons I began to write about chaos magic in the first place came out of reading a book on chaos magic that described it in a way that was utterly foreign to my experience. I thought I could do something better. I believe I have.

Peter J. Carroll once quipped that “I’m sick of occult ideas that pass from book to book without any intervening thought.”

I do feel that’s an important point that needs some attention. Occult ideas do tend to get repeated. The same ideas are continually recycled, maybe with just a little bit of tweaking here and there. There is safety in conformity, in going along with what everyone else is saying. It’s sometimes not even down to the authors. Often publishers know what subjects are popular, and what sells books, and it is not unknown for a publisher to insist that an author omit unpopular subjects and cover popular ones – subjects that have a history of selling well. Fortunately, I’ve never been called upon to do that, but I do know authors who’ve had their work cut about like this.

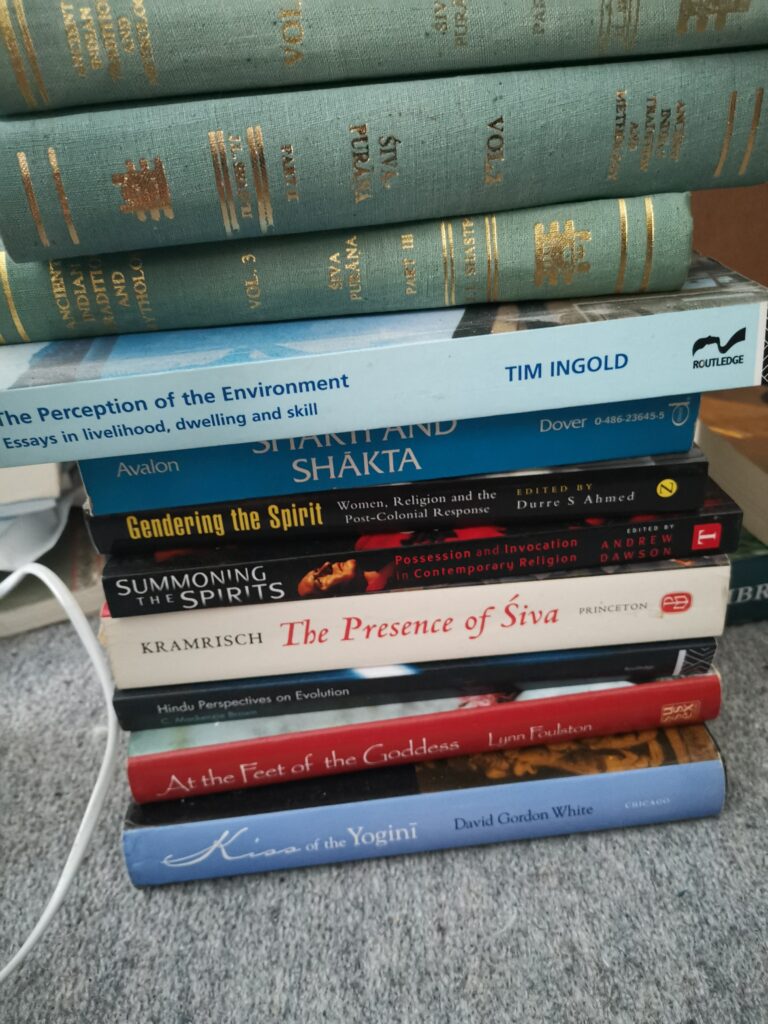

Allow me to indulge in another illustrative example. One of my more recent projects has been a series of four booklets tracing the development of the concept of ‘chakras’ into Western occultism from their origins in South Asian Tantra. I’ve published a series of four chapbooks on the subject, which one day I might get around to expanding into a larger work. What I hope to have demonstrated is that whilst chakras are often accorded a strong ontological status – which is to say that they are often regarded to be as real as physiological organs; the popular ideas about chakras now circulating endlessly through books, internet forums, and websites, are not simply eternal truths. They emerged out of a complex series of intercultural encounters, over a period of at least 150 years of modernity, and prior to that, have a history in India that can be traced back to the fifth century of the common era, but again, evolved over time.

These books have been well-received for the most part, although they have made some people – who want to see chakras in terms of “timeless occult truths” – angry. But of course, I didn’t always think about chakras in this way. Looking back in my diaries, I have found entries from the 1980s where I talk about “feeling my base chakra opening like a flower” in response to a feeling or vision. I had, I now think, absorbed some author many years ago, going on about chakras opening, and almost unconsciously took that idea on board, without consciously stopping to think about it. It became a framework for organizing and understanding my experiences. I accepted it as the truth. Now I know differently. The idea that chakras can be opened, closed, or blocked is an entirely modern innovation from the early twentieth century.

There is something rather wondrous, nonetheless, about the human capacity to internalize a schema for making sense of our experiences so that it becomes embodied. We don’t merely know something to be true intellectually. We feel that it is true through our bodies. I mention this in Condensed Chaos; the ability for example to spend a period of time feeling our experiences according to the central spheres of the Qabalah when doing an exercise such as the Middle Pillar. Then perhaps moving on, so that we experience our sensations, feelings, and emotions to correspond with the seven chakras as we tend to know them. But neither schema has to be accepted as an ‘absolute truth’ (unless you want to).

What all this boils down to is that I believe it is conducive to reading occult books that we ask questions of them. We should neither accept the words before us uncritically nor perhaps should we dismiss them out of hand, but we do need to pay them attention, if only out of respect for the work that an author has put into them. I remember at one time or another making notes as I read a book. Mostly this was because at that time I couldn’t actually afford to buy books, and this was a way of taking something home. But it is a useful exercise, when reading a book, to make a note of anything that you don’t understand, an assertion that conflicts with something you already know or want to check up on later. The internet of course, makes this kind of reading easier by several orders of magnitude. It simply wasn’t an option when I was beginning my occult journey. Too much skepticism can bar us from exploring new worlds and taking in new perspectives, but a dash of it can be enormously helpful.

Another issue is that occult authors, with some notable exceptions, are not very good when it comes to being clear where a particular concept or idea came from. I have done this. None of my early books are particularly good at stating where I picked up a particular idea. I’ve become better at this. More recent essays do cite sources. There are even footnotes sometimes. Some people don’t like this. They feel it breaks the flow of the narrative. Or that the author is aiming for some kind of ‘academic respectability’ that they do not really merit. But it can also act as a kind of gatekeeping – denying others their right to check sources or draw their own conclusions. To check if an author is actually saying something accurate to the original source, or has hopelessly mangled it in the retelling (again, I’ve done this myself on several occasions).

But if you want to engage your readers, to invest them with the same passion that you have for a subject, then is it unreasonable to expect them to want to know more? Readers are generally interested, I’ve found, in how I’ve arrived at a particular perspective, and if they can follow these perspectives through by going to the texts that have excited me so much that they shaped my ideas significantly, then so much the better. Maybe they will read them in ways I did not, and discover things I missed. I do hope so.

Notes:

- Gareth Knight, A Practical Guide to Qabalistic Symbolism (republished by Red Wheel/Weiser, 2001). Knight does say in his new preface, that “it is a cause of great regret to me if, as a result of my words, anyone has been given a bad time on account of their sexual orientation.” But of course, the original words have been left in place in the new edition. ↩