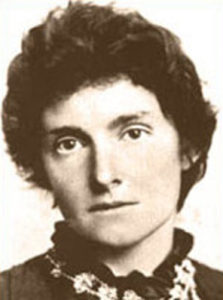

Jottings: Edith Nesbit and the Golden Dawn

Shortly after completing my recent post on Henry O’Brien I started thinking about who would be a good subject for continuing my series on Pan, and Edith Nesbit came to mind as a possibility. Pan gets a walk-on part (although he is not named directly) in Nesbit’s 1907 children’s story The Enchanted Castle. I thought that might be a good starting point to look at Pan as a figure in Edwardian children’s literature, perhaps then going on to more well-known stories such as Barries’ Peter Pan and Graham’s The Wind in the Willows. What would also, I thought, make a look at Nesbit interesting is her connection to The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, so I set out, as a matter of first business, to find a reference confirming this.

Dig around on the internet or in any of the more recent works on the Golden Dawn and Victorian occultism, and you’ll see Edith Nesbit listed as a member of the Golden Dawn. Alex Owen, for example, in her 2004 book, The Place of Enchantment: British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern lists Nesbit as a member, as do many other modern works. Yet few authors do more than give Nesbit this place in the Golden Dawn’s annals – I’ve seen nothing (thus far) in the way of conclusive evidence or substantial discussion on the matter. I did find an interesting paper by Brynne Laska entitled “Magical Materialism: The Role of Costume in the Rituals of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and E. Nesbit’s The Enchanted Castle (Vides, 2015, Volume III) which proceeds entirely on the basis that Nesbit was a member of the Golden Dawn, although like many others, she does not offer any conclusive proof.

Dig around on the internet or in any of the more recent works on the Golden Dawn and Victorian occultism, and you’ll see Edith Nesbit listed as a member of the Golden Dawn. Alex Owen, for example, in her 2004 book, The Place of Enchantment: British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern lists Nesbit as a member, as do many other modern works. Yet few authors do more than give Nesbit this place in the Golden Dawn’s annals – I’ve seen nothing (thus far) in the way of conclusive evidence or substantial discussion on the matter. I did find an interesting paper by Brynne Laska entitled “Magical Materialism: The Role of Costume in the Rituals of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and E. Nesbit’s The Enchanted Castle (Vides, 2015, Volume III) which proceeds entirely on the basis that Nesbit was a member of the Golden Dawn, although like many others, she does not offer any conclusive proof.

Fortunately, there is a good deal of scholarship on Edith Nesbit (she is perhaps most famous for her 1906 book The Railway Children) and there have been several biographies of her written over the years. Noel Streatfeild’s enticingly-titled 1958 book Magic and the Magician: E. Nesbit and Her Children’s Books did not, perhaps unsurprisingly, mention her involvement with the Golden Dawn. I then obtained Julia Briggs’ 1987 biography, A Woman of Passion: The Life of E. Nesbit 1858-1924. Briggs does not mention Nesbit having any involvement with the Golden Dawn either. I then turned to a very recent biography – Eleanor Fitzsimons’ 2019 The Life and Loves of E. Nesbit: Victorian Iconoclast, Children’s Author, and Creator of The Railway Children.

Here’s what Eleanor Fitzsimons has to say on the subject of Nesbit’s membership of the Golden Dawn:

“Edith’s reputed membership in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the foremost occult organization of the day, is intriguing. … Most biographical accounts suggest that Edith was a member of the Golden Dawn, but evidence to support this is rarely cited. The organization was of course secretive by nature, but eyewitness accounts never mentioned her as they did others, and her name does not appear on the rolls.”

I’m inclined to fall on the side of caution, as Fitzsimons does, if only because of the scholarly interest around Nesbit and her works. If she had been a member of the Golden Dawn, one would think someone would have established that more firmly than a mere assertion in passing. I have Franny Moyle’s excellent biography of Constance Wilde in mind here (Constance: The Tragic and Scandalous Life of Mrs. Oscar Wilde John Murray Press, 2012). If Constance Wilde’s involvement in the Golden Dawn has been verified, why can this not be done for Edith Nesbit?

An intriguing theory has emerged from my asking questions on social media. My old friend from the Wakefield Pagan Moot, Steve Jones, has suggested that persons unknown may have confused Edith Nesbit with one Agnes Elizabeth Nisbet (1864-1947) who does appear on the membership roll of the Golden Dawn.

Gradually, I began to wonder from which source Edith Nesbit’s alleged membership of the Golden Dawn came from. She’s not mentioned in Mary Greer’s Women of the Golden Dawn for example. Eventually, I found an early reference in Ithell Colquhoun’s (1975) book Sword of Wisdom – where she opines that Nesbit was a member of the Stella Matutina, and remarks that this association may have been “a passing enthusiasm”. Colquhoun apparently picked this up from James Webb’s 1971 book The Flight from Reason. Opening up Webb’s “The Occult Underground” (which was the name Reason was republished as) he does indeed state that Nesbit was a member of the Stella Matutina, but as far as I can see, does not offer any evidence to back this up. An even earlier source is Francis King’s 1970 book Ritual Magic in England – republished in 1989 by Prism Press as Modern Ritual Magic: The Rise of Western Occultism. King says, in a footnote on p186: “The Stella Matutina included several members of the Fabian Society in the ranks of its initiates, among them Herbert Burrows and E. Nesbit (Mrs. Hubert Bland) the writer of children’s stories.”

It’s the identification of Herbert Burrows as a member of the Stella Matutina which causes me to doubt this attribution, as Burrows was very active in the Theosophical Society. Although again, I have been as yet unable to corroborate any connection between Burrows and the Stella Matutina, I somehow doubt he would be involved in a ceremonial magic lodge.

With thanks to Eleanor Fitzsimons, Steve Jones, and Richard Kaczynski.

One comment

Haptalaon

Posted February 19th 2021 at 5:05 pm | Permalink

I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on Edwardian children’s Pan; I’ve been putting together a reading list of books of this kind, vaguely associated with re-enchantment and going back to childlike imagination as a devotional practice, vaguely associated with a pop-culture-paganism that looks more at later sources than reconstructionist Pan.

(I’ve yet to find anything remarkable or new – I’m not wholly sure where to look – but Syd Barrett comes up in an ideosyncratic way; the 70s rock pastoral-weirdness-English-victoriana trend is also one that interests me)

The 20s Pan resurgence just feels like, an interesting moment in how people were feeling about religion and the land and the past, especially as a nostalgic figure (and nostalgia is always interesting).

(this is slandweird from twitter; thank you again for the references on Constance Wilde)