Exhibition review – Tantra: enlightenment to revolution

At the British Museum, 24 Sep 2020 – 24 Jan 2021

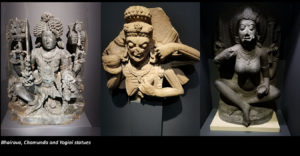

The British Museum’s new exhibition Tantra enlightenment to revolution is a stunning tour through the influence of tantric culture across South Asia and beyond. Curated by Imma Ramos, the collection begins with the early influences of tantric iconography with some fine representations of Bhairava, through to Buddhist influences, and the rise of Tantric traditions in Tibet, Nepal, and Japan. There is a dizzying array of material artifacts, ranging from statues to ritual objects and artworks.

The exhibition also takes in colonial-era representations of tantric culture – most famously in the representations of the goddess Kālī and then looks beyond to the neo-tantric art movement of the 1960s, tantric themes in counter-culture, and contemporary artworks. The explainer boards complemented the objects very well, being concise, accurate, and accessible, and the static works are complemented by audio-visual displays. In previous visits to British Museum exhibitions I’ve often ended up feeling “overloaded” with visual imagery, but not this time. Despite the amazing array of images and objects on display, the subdued lighting of the spaces helped a lot in this respect.

One of the highlights of the exhibition for me was an “Imaginative recreation” of the famous Hirapur Yoginī temple in Odisha – a semi-circular space in which, arrayed at waist-height were twelve high-quality photographs of Yoginīs. The top half of the space was devoted to a ghostly, shifting montage of images of Yoginīs, with text and audio quotations from the Brahmayāmala tantra (see this post).

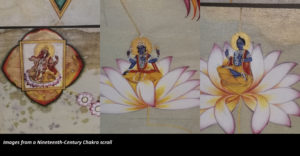

Items relating to the practice of Yoga and the chakras are also present, with some images of Yogis performing asanas, Sufi ascetics, and a floor-to-ceiling high scroll – probably a commission from a courtly patron – depicting a seven-chakra arrangement, with the devas of the chakras clearly visible.

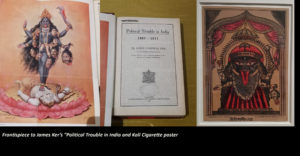

I was also interested to see the colonial representations of the goddess Kālī, and how she was viewed as a symbol of resistance in Bengal, and dangerous by the British authorities. One of the explainer boards also mentions the East India Company’s tax practices which led to the Bengal Famine of 1770. One of the books on display – James Campbell Ker’s 1917 Political Trouble in India (available in digital form at archive.org) cites several articles in Indian ‘radical’ periodicals of the period which recommend country-wide Kālī puja – and in particular, Rakshakali – to whom are sacrificed “white goats”. Ker also refers to the “ruinous folly” of several groups and individuals – including Theosophists and Vivekananda, who “actually led the average educated Hindu to believe the doctrine, that everything Indian is pure, spiritual and lofty, and that everything Western is materialistic, sensuous and devilish”. Ker also claimed that the “Muzaffarpore bomb outrage” of 1908 was “the first revolutionary sacrifice to the goddess Kali”. One of the images featured in the exhibition is a print advertising “Kali Cigarettes” which was censored by the authorities as the heads shown in the print were “too British looking”.

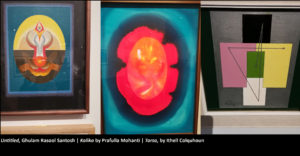

Moving out of the colonial era, the exhibition includes a representative sampling from the exponents of the Indian “Neo-Tantric” art movement, which emerged in the 1960s as a form of Indian abstraction developed by artists such as Biren De, K.V. Haridasan, Shankar Palsikar and Ghulam Rasool Santosh. The exhibition shows works by Biren De, Ghulam Rasool Santosh, and Prafulla Mohanti. The exhibition also gives a small sample of western countercultural productions, with two works from Ithell Colquhoun, Penny Slinger’s “Rose Devi” and “Chakra Devi”, and a “Tantric Lovers” poster from Oz magazine by Nigel Waymouth and Michael English. A surprise revelation was that the iconic lips and protruding tongue logo used by the Rolling Stones and designed by John Pasche were originally inspired by representations of Kālī!

The last part of the exhibition highlights the work of two contemporary artists; Sutapa Biswas’ 1985 “Housewives with Steak-Knives” which evokes the goddess Kālī as a defiant feminist icon, and Bharti Kher’s 2008 “And all the while the benevolent slept” – a dramatic and playful depiction of the self-decapitated Chinnamasta, holding a teacup – an allusion to “British civility” apparently, and a reproduction of the fossilized skull of “Lucy,” the oldest-known human ancestor.

The last part of the exhibition highlights the work of two contemporary artists; Sutapa Biswas’ 1985 “Housewives with Steak-Knives” which evokes the goddess Kālī as a defiant feminist icon, and Bharti Kher’s 2008 “And all the while the benevolent slept” – a dramatic and playful depiction of the self-decapitated Chinnamasta, holding a teacup – an allusion to “British civility” apparently, and a reproduction of the fossilized skull of “Lucy,” the oldest-known human ancestor.

All in all, this is a fantastic exhibition and well worth braving public transport and social distancing to visit!

Online

Tantra enlightenment to revolution Exhibition details

Exhibition Catalogue

Artworks by Bharti Kher

2 comments

William

Posted October 2nd 2020 at 10:22 am | Permalink

Thanks for the review. As one with some familiarity with the field, your thoughts are helpful. Hoping the viral weather improves such that even we pilgrims from the continent may make the journey across the Great Water.

Mike Magee

Posted October 2nd 2020 at 9:38 pm | Permalink

Yeah, of course the Raj fable about Kālī being the deity of the mystic thugees was designed to divide and conquer, viz the first Indian war of independence.