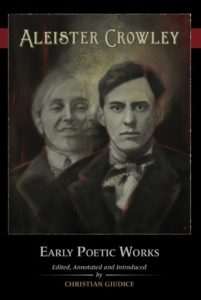

Book Review: Early Poetic Works by Aleister Crowley edited by Christian Giudice

The Early Poetical Works of Aleister Crowley as published here (Kamuret, London: 2019) comprise four of his earliest published books: Aceldama: A Place to Bury Strangers, Jezebel and Other Tragic Poems, Songs of the Spirit, and The Tale of Archais: A Romance in Verse. They are provided with a fulsome introduction by Chris Giudice. All four of these collections are near impossible to find in their original state, largely due to their limited original print runs. To be able to hold them all in hand at one time is a huge benefit to the student of Crowley and this volume should be hailed for that alone.

The introduction and the presence of all four collections presents the reader with two ‘ways of looking’ at the work. On the one hand, we look outwards, to the poetic movements and traditions that influenced Crowley and try to understand where he sits as a poet in relation to those. On the other hand, we look inward to the person presented in these poems and to Crowley’s first significant romantic relationship: a brief but passionate meeting of minds and bodies with one of the best-known female impersonators of the day, Jerome Pollitt. The introduction, the commentaries which follow the texts, and the four collections together make for a heady mix and offer a new ‘sense’ of Crowley at this youthful point in his life: all of the poems in this book would have been written before the age of twenty-four.

Giudice argues that Crowley’s poetry should be seen as a part of, perhaps even the last flowering of The Decadent Movement in literature that swelled into life and was gone again all within the last few years of the nineteenth century. It began in France with a loose group of writers in the vein of Charles Baudelaire and spread to a similar group in London who included Ernest Dowson, Lionel Johnson, John Gray, Oscar Wilde, Theodore Wratislaw and others. It was a group whose writing compassed themes of sensation, malady, dissipation, perversity, and decay, often in a world-weary tone. Guidice traces Crowley’s links to this group through Jerome Pollitt who was very much involved with them and who introduced Crowley to Beardsley and, perhaps more importantly, to the pornographer and publisher Leonard Smithers. Though Crowley met Beardsley and was clearly impressed by him, enough to name check him in poetry and to dedicate one of his books to him, it cannot be said that Crowley was a part of the more London-based group of Decadent writers on a personal level. He would, however, have been very aware of their writing having spent his time at Cambridge in a promiscuous deep dive into reading all the poetry his deep pockets could acquire.

Giudice argues that Crowley’s poetry should be seen as a part of, perhaps even the last flowering of The Decadent Movement in literature that swelled into life and was gone again all within the last few years of the nineteenth century. It began in France with a loose group of writers in the vein of Charles Baudelaire and spread to a similar group in London who included Ernest Dowson, Lionel Johnson, John Gray, Oscar Wilde, Theodore Wratislaw and others. It was a group whose writing compassed themes of sensation, malady, dissipation, perversity, and decay, often in a world-weary tone. Guidice traces Crowley’s links to this group through Jerome Pollitt who was very much involved with them and who introduced Crowley to Beardsley and, perhaps more importantly, to the pornographer and publisher Leonard Smithers. Though Crowley met Beardsley and was clearly impressed by him, enough to name check him in poetry and to dedicate one of his books to him, it cannot be said that Crowley was a part of the more London-based group of Decadent writers on a personal level. He would, however, have been very aware of their writing having spent his time at Cambridge in a promiscuous deep dive into reading all the poetry his deep pockets could acquire.

Giudice successfully traces the influences on Crowley’s work of Shelley and Swinburne. It is in Shelley’s Rosicrucian interests and his belief in the Great White Brotherhood of adepts who guide mankind that, Guidice claims, set Crowley’s feet on a spiritual and then an occult path and Guidice provides a detailed analysis of the connections between works such as Shelley’s Queen Mab and Zastrozzi with Crowley’s poems. In Swinburne, who was still living when Crowley was writing, we find the merging of sexual and spiritual themes, particularly sado-masochistic elements as a route to spiritual experience or even enlightenment. For Swinburne the spiritually charged sex was connected to flagellation and humiliation in a heterosexual context: Crowley, however, was branching out at this point in his life and beginning to experience and come to terms with his bisexuality.

It was at Cambridge that Crowley met and was seduced by, probably quite willingly, the female impersonator and actor Jerome Pollitt. The relationship and the poetry it produced have been picked over before, notably by Richard Kaczynski in his biography of Crowley, Perdurabo. But Giudice has a little more space and focus here than a biographer and is able to give more of a sense of Pollitt as a man and his significance to Crowley even long after the relationship had ended (and the photographic illustrations are particularly strong on images of Pollitt both in and out of drag). Many of the poems in the book were either addressed to or were influenced by Crowley’s feelings for Pollitt and in the introduction and commentaries, Giudice unpicks where these references are. Whilst it is always interesting to hear how people negotiated same-sex relationships in times past, the real interest in these poems as they relate to Pollitt is how Crowley interprets his sexual experiences in magical and occult terms.

It is genuinely striking how many of the themes of Crowley’s mature thought and magical praxis are present here in his early twenties. The idea of sin turns over and over in his poems as a path to redemption; degradation leads to enlightenment; insanity brings clarity; gender moves back and forth in the same person in a way that is revelatory. And these were not just experiences that Crowley was imagining. The relationship with Pollitt is fascinating for the many ways it cracks open the stereotypes of gender and role which persist even today. Crowley is most often presented to the world by himself and by his biographers as a dominant personality, one who was able to manipulate and dominate his friends, lovers, and associates; so to realize that he took the passive, maybe submissive role, in his sex life with Pollitt is worth thinking about. Pollitt was the slightly older partner and yet also a female impersonator, and whilst there is no suggestion that Pollitt spent time in drag outside the theatre, let alone inside the bedroom, this world of high-camp and female dressing adds another dimension to the gender and sex roles between the two. As Giudice points out Crowley himself said: “I lived with Pollitt as his wife for some six months and he made a poet out of me.” For Crowley, there is no doubt that the taboo-breaking, sometimes painful and often overwhelming experience as the passive partner in homosexual sex was an experience in which he found elements of both initiation and revelation. It was this which he explored in his Pollitt-inspired poetry. Later, this passive role would become a route to possession in magical workings. In ‘Jezebel’ a prophet of Yahweh is bewitched by the ‘wicked’ Queen Jezebel when she spits in his face. Though the prophet continues to profess and speak for Yahweh, he harbours a raging desire for her to dominate him right to the end. It is to be wondered if Crowley’s various scarlet women, his incarnations of Babalon make an early appearance here and if that is true, was Pollitt, in fact, the first of his scarlet women?

Crowley as a poet is a difficult proposition. Although Giudice offers an excellent analysis of the influences on his poetry, the poetry itself will always be more interesting to those interested in his biography and his magical teachings. Largely this is because, although it can be demonstrated that he stood in a poetic tradition, he himself did not influence others, he has no poetic legacy beyond his own work. Crowley, in his Confessions, praises Aceldama as containing his best work, his praise for it is ridiculously over the top. However, he is also probably right that his best work was his earliest and it declined as he went on. This may, in fact, be a demonstration of the truth of his claim that it was Pollitt that made him a poet; beyond what he was learning from his relationship with Pollitt, Crowley had much less to say in poetic form.

There is an issue with the collection of the four books in this volume and Giudice acknowledges it head-on; it omits the pornographically inclined collection of poems that Crowley put out through Leonard Smithers called White Stains. It is true, as Giudice says, that White Stains has been reprinted numerous times, and that it doesn’t bear the same hallmarks of standing in the poetic tradition as the four books here reprinted. It would have required a slightly different approach in the introduction had it been included. Perhaps it was a lost opportunity, or perhaps it leaves open an opportunity for someone else. White Stains is not now the only sexually explicit poetic work we have from Crowley, the existence of a small unpublished book known as ‘The Amsterdam Notebook’, also inspired by the sexual and spiritual revelations that Crowley was experiencing with Pollitt, has recently been made public. To integrate the whole range of Crowley’s poetic output from this period might be the next project.

This is a handsome volume and the editor is also the publisher, which can sometimes be a concern but not in this case. The book has been produced with great care and to the highest standards of both scholarship and presentation. It is a great blessing to be able to access all these works by Crowley in one volume and to have it so expertly contextualized and explained.