Book Review: Chernobyl: A Stalkers’ Guide

I was 26 when the Chernobyl disaster occurred, and I well remember my feeling of horror and incredulity as the scraps of information filtered through and friends speculated what effects it might have on the magic mushroom season that year. I grew up in the shadow of the bomb – the three-minute warning, “Protect and Survive” and the War Game. Many of us had half-expected something like Chernobyl was only a matter of time. Over the years I’ve become fascinated with Chernobyl, its history and the mythologies it has spawned. I have spent hundreds of hours exploring the virtual simulacra of the Zone in the S.T.A.L.K.E.R trilogy of games and the two free mods, Lost Alpha and StalkerSoup. These games owe as much to Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s 1972 novel “Roadside Picnic” and Andrei Tarkovsky’s haunting film “Stalker” as they do to any real events, but if there is any place on earth where the borders of the real and the imaginary might collapse, it is Chernobyl.

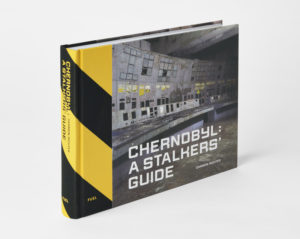

This is the territory explored by Darmon Richter in his wonderful new book Chernobyl: A Stalkers’ Guide (Fuel Design 2020, 160x200mm hardback, 248 pages). This wide-ranging and thoroughly-researched book, lavishly illustrated with colour maps, diagrams and the author’s own stunning photographs is quite the best book I have yet read on Chernobyl and the Exclusion Zone. Richter has traveled widely across the zone, taking both the “official” tourist trips and dodging the police patrols with the unofficial stalker-led trips that take him into dangerous areas such as the Red Forest, and even into the restricted areas of the Power Plant itself. He explores the effects of tourism on the Zone, and how popular destinations such as the city of Pripyat have become mythologized – turned into set-pieces that both reflect and reify visitor’s expectations. He visits the infamous Duga-1 radar array – the subject of Chad Gracia’s 2015 documentary “The Russian Woodpecker” as well as less well-known sites off the tourist routes – abandoned factories and half-forgotten Soviet-era monuments.

This is the territory explored by Darmon Richter in his wonderful new book Chernobyl: A Stalkers’ Guide (Fuel Design 2020, 160x200mm hardback, 248 pages). This wide-ranging and thoroughly-researched book, lavishly illustrated with colour maps, diagrams and the author’s own stunning photographs is quite the best book I have yet read on Chernobyl and the Exclusion Zone. Richter has traveled widely across the zone, taking both the “official” tourist trips and dodging the police patrols with the unofficial stalker-led trips that take him into dangerous areas such as the Red Forest, and even into the restricted areas of the Power Plant itself. He explores the effects of tourism on the Zone, and how popular destinations such as the city of Pripyat have become mythologized – turned into set-pieces that both reflect and reify visitor’s expectations. He visits the infamous Duga-1 radar array – the subject of Chad Gracia’s 2015 documentary “The Russian Woodpecker” as well as less well-known sites off the tourist routes – abandoned factories and half-forgotten Soviet-era monuments.

A tame fox poses in front of the sign pointing the way to Pripyat from the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. (© Darmon Richter / FUEL Publishing)

But as much as it is about place, Chernobyl: A Stalkers’ Guide is about people too. Richter has also interviewed a wide range of people whose lives have been impacted or changed by the Chernobyl catastrophe, ranging from those who still live in the exclusion zone, to Stalkers, those involved in the cleanup operation, and former personnel of the Power Plant. I was intrigued to learn for example that some of the stalkers Richter spoke to were drawn to the Zone through playing the S.T.A.L.K.E.R games. There are clearly tensions between the monetization of the Zone, the application of labels such as “disaster tourism”, those who feel that the area should be protected and preserved. Richter deals with the complexities of the Zone’s various interest groups and micro-communities ably and sensitively – even documenting the existence of a rave and performance counter-scene.

Richter also presents some fascinating side-trips – such as the species of black fungi that thrive in the presence of radiation, and the thorny issue of “Nuclear Semiotics” – how to devise warnings about nuclear waste sites that will be meaningful to future generations. All in all, Chernobyl: A Stalkers’ Guide is essential reading for anyone intrigued by the Chernobyl disaster, its aftermath, and its future portents.