Yogis, Magic and Deception – I

This post is an extract from a recent lecture at Treadwells Bookshop, entitled “Flying through the air, entering other bodies: Yoga and Magical Powers”. The lecture examined the relationship between yoga and magical or extraordinary abilities. When I began reading for the lecture, I was very familiar with the anti-Yoga views of 19th century scholars such as Max Muller or H.H. Wilson, but less so regarding how attitudes to yoga and yoga powers intersected with popular culture. So here is a brief examination of how yogic powers became associated with stage magic, duplicity and deception.

Over the course of the Nineteenth century, the wondrous powers of the yogi enter both popular culture and Western Esotericism, and the scientific study of yoga begins. This is the background to which our contemporary understanding of the powers of the yogi is situated. For the most part, commentators were scornful of yogic practices and viewed yogis with a mixture of suspicion and disdain. One reason that Yoga was seen as suspect in this period was its very association with magical or supernatural abilities. Whilst scholarly accounts reported feats such as the abilities of yogis to remain buried alive for weeks on end, such powers were invariably dismissed as mere trickery, self-deception – and the deception of a credulous and superstitious populace.

A common theme in orientalist representations of India was that of an immaculate past and a degraded present. As Max Muller put it, although Indians had, in their ancient past “reached in the Upanishads the loftiest heights of philosophy” Hinduism was “now in many places sunk into a grovelling worship of cows and monkeys.” Muller, in his study and translation of Vedic texts, believed that Indian religion had been originally, monotheistic, but later decayed into polytheism and magic. Like many of his contemporaries, he believed in an evolutionary progression of religion – that lower forms of religion evolve into higher forms. But religions could also decay and become corrupt. Indian religious practices were judged as promoting idolatry and superstition – and anything that smacked of “magic” was seen as demonstrating the truth of this argument.

This trope of India’s glorious past and degraded present can be seen – in varying degrees – in many 19th and early 20th century explanations of yoga. For example, it became a common tactic to separate the noble philosophy of Yoga from its actual practitioners. Muller, in his 1899 book The Six Systems of Indian Philosophy engages in a lengthy discussion of yoga philosophy, but dismisses the “postures and tortures” in Pātañjali’s Yoga Sutra, deeming them to be a corruption of the original philosophical tradition.

Yet at the same time that scholars were doing their best to distinguish a noble yoga philosophy from the degradations of yogi practitioners, the mysterious powers of the yogi were filtering into European and American popular culture.

In 1830, a story appeared in the Saturday magazine giving an account of one Sheshal, who was dubbed “the Brahmin of the Air” due to his apparent ability to sit cross-legged in the air, with one hand resting on a staff that touched the ground. The Air Brahmin excited much comment and newspaper coverage, and despite the eventual exposure of the trick continued to be a source of wonderment.

It was the fascination with these apparent powers which led to the formulation of the first “scientific” explanation for yogic abilities – hypnotism. In Lahore, 1837, a fakir was reported to have remained buried alive without food or water for an entire month. James Braid, the father of modern hypnotism, used accounts of this and similar incidents to argue, in his 1850 work Observations on Trance or Human Hibernation, that such feats were the result of self-hypnosis. The “hypnosis” explanation for yogic powers became very popular and indeed, continues today.

Naturally, these yogic feats quickly drew the attention of English stage magicians and conjurors. The first English conjuror to have performed in Indian guise was Charles Dickens! In 1849 Dickens, a keen amateur conjuror had blacked up his face and hands, dressed in exotic robes, and presented himself as ‘The Unparalleled Necromancer Rhia Rhama Rhoos’.

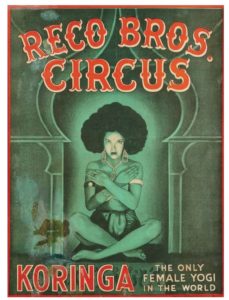

Over the course of the century, stage magicians performed various versions of Indian feats, either presenting themselves as fakirs or claiming that they had traveled to India to learn the secret arts. The French performer Renee Bernard, aka “Koringa” was billed as being raised by Fakirs and taught the arts of sorcery.

Over the course of the century, stage magicians performed various versions of Indian feats, either presenting themselves as fakirs or claiming that they had traveled to India to learn the secret arts. The French performer Renee Bernard, aka “Koringa” was billed as being raised by Fakirs and taught the arts of sorcery.

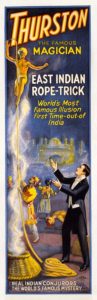

The most famous “yogic feat” is, of course, the so-called “Indian Rope Trick”.

The most famous “yogic feat” is, of course, the so-called “Indian Rope Trick”.

The first report of this startling feat appeared in the Chicago Daily Tribune in 1890. A Yogi or Fakir raised a rope into the air using his mind power, then an assistant – a young boy, climbed to the top of the rope and disappeared! The Fakir then called to the boy, then, growing angry, followed him up the rope and disappeared too! Then body parts of the boy rained down from the top of the rope. The Fakir then reappeared, climbed down the rope and placed the body parts into a basket, out of which the boy sprang, unharmed. This feat of illusion – usually performed far less elaborately, became popular across Europe and America. Some months after the original account was published, the editor of the Tribune admitted that it was a hoax. But by that time, the story had been widely repeated and it wasn’t long before witnesses appeared who had claimed to have seen it performed.

In 1899 a British Stage Magician, Charles Bertram, traveled to India, offering a reward of £500 to any Indian Fakir who could perform the trick to his satisfaction. Apparently no one could. Explanations for the trick included mass hypnotism, mesmerism, or the idea that the witnesses had imbibed too much hasheesh.

Some British stage magicians embarked on a campaign to discredit Indian tricks and their association with magical powers. In 1878 the conjurer John Nevil Maskelyne wrote an article on “Oriental Jugglery” complaining of fakirs who deluded innocent Englishmen into believing that their tricks were due to some element of the marvelous. He went on to reveal the methods by which some famous tricks had been accomplished. Other conjurors followed suit – the general tone being that Indian tricks were inferior to those performed by European conjurors. Maskelyne went on to expose fraudulent mediums in a similar manner.

Over the course of the Nineteenth century, yogic abilities were increasingly taken as evidence of both “the mystic east” and Indian duplicity, superstition and fraud. What interests me, in particular, was how far these popular representations shaped the negative view of Yogic powers which can be seen in the writings of Western Esotericists such as Madame Blavatsky and Aleister Crowley.

Sources

Sarah Dadswell Jugglers, Fakirs, and Jaduwallahs: Indian Magicians and the British Stage (New Theatre Quarterly / Volume 23 / Issue 01 / February 2007, pp 3 – 24).

Peter Lamont and Crispin Bates Conjuring images of India in nineteenth-century Britain (Social History Vol. 32 No. 3 August 2007).

Arie L. Molendijk Friedrich Max Müller and the Sacred Books of the East (Oxford University Press 2016).

Mark Singleton Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice (Oxford University Press 2010).

Sharada Sugirtharajah Imagining Hinduism: A postcolonial perspective (Routledge 2003).