Theosophy and Race – III: India’s Aryans – I

“We see a reunion of parted cousins, the descendants of two different families of the ancient Aryan race.”

Kenshub Chandra Sen, 1877

In the opening part of this series, I examined the roots of the notion of the Aryans in the work of Sir William Jones and Freidrich Max Müller. In the second post, I briefly outlined the emergence of nineteenth-century racial science, and how the concept of Aryans became associated with white supremacy and racial hierarchies.

Aryan racial theory, as it developed, seemed to raise as many issues as it purported to solve. If Indians and the British shared a common ancestry, this threatened the belief that Indians were inferior to Europeans. The answer, for some, lay in a Darwinian notion of racial degeneration. This led to the notion that whilst the European Aryans had maintained their vitality, the Indian Aryans had degenerated, by intermingling with the aboriginal natives – weakening their bloodlines and adopting superstitions and primitive practices. In the pens of the European racial theorists, India’s Aryan past became a kind of golden age, from which India had sadly declined into superstition and idolatry. These ‘explanations’ had far-reaching consequences.

Before I get around to examining how the Theosophical Society adopted the Aryan concept, I want to explore how the Aryan concept was received in India itself. I will begin with a brief account of the Brāhmo Samāj, and in the next post, move on to look at Dayānand Saraswatī’s Ārya Samāj – which was embraced (for a while) by Madame Blavatsky and Colonel Olcott.

Just as the concept of the Aryans was seized on and deployed by European orientalists, missionaries, and other interest groups in a variety of ways, so too was the response in India. Some welcomed Müller’s work as evidence of equivalence between colonizer and the colonized, whilst for others, it signified the superiority of spiritual Indian Aryans against the materialistic West. Others sought to establish compatibility between the Vedas and Christian doctrine or to argue for or against the supremacy of the Brahmans.

“Max Mueller’s scholarly theories concerning the common origin of all Indo-Aryan races based on his linguistic studies were received with incredible enthusiasm. The belief that the white masters were not very distant cousins of their brown Aryan subjects provided a much needed salve to the wounded ego of the dependent elite. A spate of ‘Aryanism’ was unleashed. The word ‘Aryan’ began to feature in likely as well as likely places-from titles of periodicals to the names of street corner shops. Even the serious writers of the period were not unaffected by this particular plague. The Tagores-Rabindranath and Dwijendranath-might poke fun at the new Aryanism, but they were almost certainly in a minority and it is doubtful if their irony was appreciated by many.”

Tapan Raychaudhuri, 1988, p8.

One way in which Müller’s theories had influence was in relation to social and cultural reform movements. Jyotirao Govindrao Phule (1827-1890) for example, used Müller’s work to propose that the lower castes – the dasas and shudras of Brahmanical texts were the indigenous inhabitants of India who had been subjugated by the invading Aryans. In his book 1873 Gulamgiri, he expressed gratitude to the British for helping the lower castes realize they too were worthy of rights. His views were not widely accepted at the time, although he is credited with coining the word ‘dalit’.

In 1828 the Bengali Brahman Raja Rammohun Roy (1772-1833) founded the Brāhmo Sabhā – which later (1943) was known as the Brāhmo Samāj. Roy’s father’s family were followers of Chaitanya, whilst his mother’s family were Śaivites. In addition to his native Bengali, Roy studied Persian and Sanskrit. In 1804 he produced his first challenge to orthodox beliefs, in a Persian tract called A Gift to Deists, in which he set forth his opposition to idolatry and polytheism. He went on to a career in banking and worked for the East India Company for nine years. He retired in 1814 to devote his considerable energies to social and religious reform.

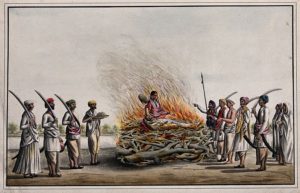

One of the first issues Roy dealt with was the ritual of satī – the immolation of Hindu widows on their husband’s funeral pyre. The practice was popular amongst high caste Bengalis, and Roy had been deeply affected when one of his female relatives committed satī. In 1818 he published A Conference Between an Advocate for and an Opponent Of the Practice of Burning Widows Alive – citing scriptural sources in order to demonstrate that satī was not required by Hindu law. Satī had been, for the most part, ignored by the colonial government, taking the stance that although it was a “repugnant” custom, it was legal under Hindu law. In the early part of the nineteenth century, some efforts were made to regulate the practice, banning the practice for women under the age of sixteen for example, or those who had young children, for whom no support was available. Missionaries such as William Ward (see this post for more on Ward) also actively campaigned for the government to ban the practice, condemning it as barbaric and an example of Indian superstition and idolatry.

Roy continued to campaign against satī – engaging in debates in the newspapers, and publishing further pamphlets arguing against the practice. His tracts were published in English, and circulated in Britain by supporters. The Governor-General, William Bentick, ordered a regulation prohibiting sati in December 1829. When orthodox Hindus petitioned against the regulation, the matter was referred to the privy council 1 Roy traveled to England to give evidence to Parliament on the matter. Müller, commenting on Roy’s visit later in 1883, hailed the event as “the meeting again of the two great branches of the Aryan race, after they had been separated so long that they had lost all recollection of their common origin, common language, and common faith.” 2

Roy embraced a universalist perspective on religion – Unitarianism – believing that all religions had equal merit, although a rational approach to faith was required to purge them of superstition, myth, and unnecessary ritual. The Unitarians also stressed the necessity for social reform. In the words of the American Unitarian William Ellery Channing, the faith’s central message was that “every human being has a right to all the means of improvement that society can afford.” Roy’s primary aim was nothing less than the rehabilitation of Hinduism according to Unitarian principles, along with an intense program of social reform.

In 1821, he founded a journal, the bilingual Brahmmunical Magazine, to disseminate his opinions to a literate audience. In this journal, Roy set out his argument that not only was the unity of God revealed in Vedanta, but it was in a way superior to that of Christianity. He argued that both Christianity and Hinduism had become corrupted and degenerate from their original pristine faith. In arguing against idolatry and polytheism, Roy published some of the Upanisads in Sanskrit, adding Bengali and English translations.

Rammohun Roy died in 1833, whilst on a visit to England. Ten years later, Debandranath Tagore stepped in and renamed the Brāhmo Sabhā as the Brāhmo Samāj. The Brāhmo Samāj went on to be a major influence in cultural developments in India for nigh on a hundred years – campaigning for better educational and professional opportunities for women; the modern notion of dharma as social service; the promotion of Vedanta, and the growth of political and national consciousness. It was members of the Brāhmo Samāj who helped organize the Indian Political Association – the forerunner to the Indian National Congress.

Sources

Tony Ballantyne, Orientalism and Race: Aryanism in the British Empire (Palgrave, 2002)

Edwin Bryant, The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate (Oxford University Press, 2001)

Dorothy M. Figueira, Aryans, Jews, Brahmins: Theorizing Authority through Myths of Identity (State University of New York Press, 2002)

David Kopf, The Brahmo Samaj and the Shaping of the Modern Indian Mind (Princeton University Press, 1979)

Gyan Prakash, Another Reason: Science and the Imagination of Modern India (Princeton University Press, 1999)

Tapan Raychaudhuri Europe Reconsidered: Perceptions of the West in Nineteenth-century Bengal (Oxford University Press 1988)

Romila Thapar, The Past as Present: Forging contemporary identities’ through history (Aleph Books, 2014)

Thomas R. Trautmann, Aryans and British India (University of California Press, 1997)

Notes: