Theosophy and Race – I: Orientalists and Aryans

The East, formerly a land of dreams, of fables, and fairies, has become to us a land of unmistakeable reality; the curtain between the West and the East has been lifted, and our old forgotten home stands before us again in bright colours and definite outlines.

Max Müller, 1874

It’s frequently asserted that Nazi racial ideology came directly out of nineteenth-century esoteric movements – in particular, the writings of H.P. Blavatsky and other members of the Theosophical Society. This is an over-simplification of a complex subject, and one worth examining in detail. In order to do this comprehensively, I will first take a look at some of the background context – the ideas about race that were circulating prior to the advent of the Theosophical Society. I’ll begin with a brief examination of the term “Aryan” and its tangled historical trajectory prior to its adoption by Theosophists, focusing on the influence of two orientalist scholars, Sir William Jones, and Max Müller.

Both Jones and Müller are complex figures, both immensely influential in both their own times and their legacies. Although it is impossible to disentangle their work from the wider colonial project with which they were embroiled, I feel their contributions merit more than the tendency to dismiss them as avatars of exploitation.

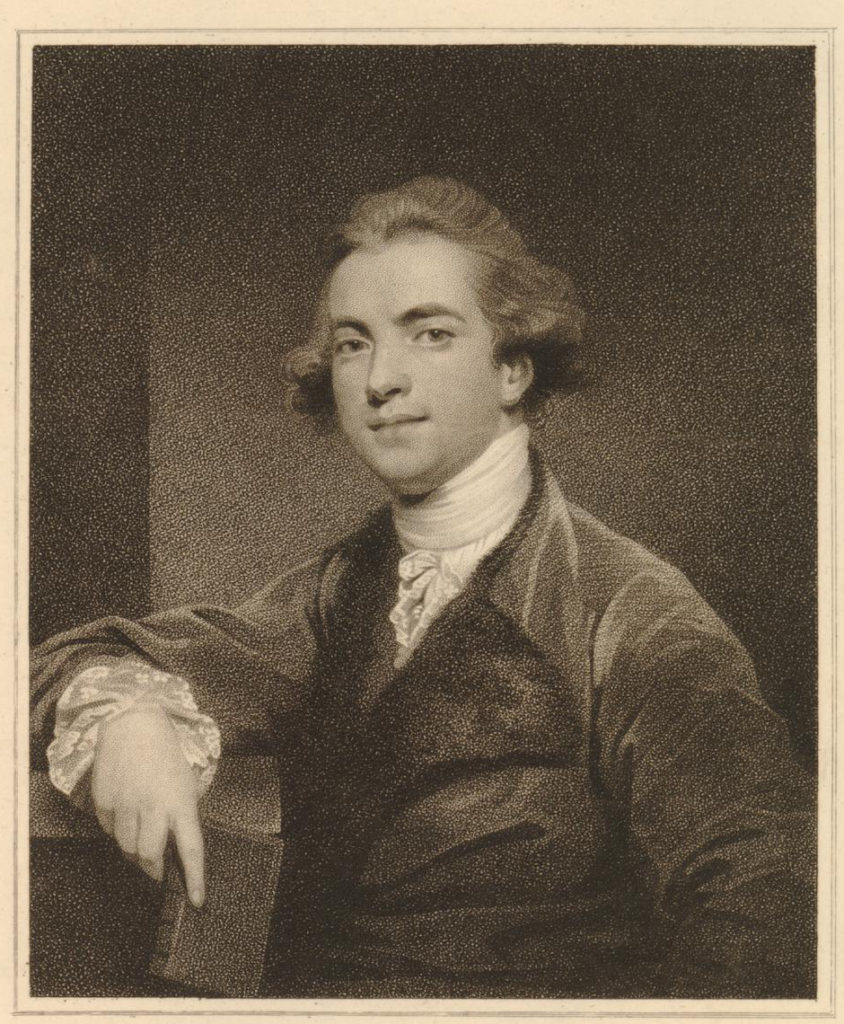

Sir William Jones

The roots of the notion of the Aryans began in the eighteenth century with the work of Sir William Jones. Jones (1746-94) is a complex figure. A radical, he believed in universal manhood suffrage, popular education, parliamentary reform, and supported the American revolution. Trained as a barrister, he had published translations of works from Persian, Arabic, and Turkish. His wide-ranging interests included music, philology, religion, poetry, politics, and law. He was knighted in 1783 and appointed a judge to serve at Fort William, Bengal, arriving in India in September of that year. Shortly after his arrival in India, Jones was appointed president of the Asiatic Society based in Calcutta. This body, sponsored by Warren Hastings, then governor of British-controlled India, was beginning the process of studying and translating Hindu texts. Hastings believed that it was information, rather than military power, that was critical to British domination of India, and that Indians should be governed through the laws which could be found in their own sacred texts, as opposed to local customs. Jones supported this view and spent much of his time in India studying the dharmaśāstras. His translation of the Laws of Manu was published after his death in 1794, for the use of English judges in India.

In 1785, Jones embarked on a study of the Sanskrit language, purely for pragmatic reasons. The first was that it would help him in his wider project of assembling a digest of Hindu law, and secondly so that he would not be reliant on Bengali pandits in delivering court judgments. In February 1786, Jones delivered a lecture to the Asiatic Society in which he announced his great discovery – the linguistic affinities between Sanskrit, Latin, and Greek – and that all three emerged from the same source. 1

“The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which perhaps no longer exists: there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothick and the Celtick, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanscrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family.” 2

Jones’ theory – that languages evolve – was radical at the time, but that was only the beginning. Jones, like many of his contemporaries, was a believer in monogenesis – the view that all humanity was descended from Noah’s three sons, and spread across the Earth. Jones’ discovery began the process of breaking linguistics away from the religious perspective that all languages originally evolved from Hebrew. Further, by stressing the common linguistic roots of Sanskrit with Latin and Greek, Jones was allowing Indian mythology and religion to be interpreted within the universal (i.e. Biblical) narrative of history, which led to developments in the comparative study of religion and culture.

Also, at a time when few Europeans had any desire to find a sense of kinship with the natives of the colonies, Jones’ theory implied a familial connection – via language – between India and Europe, and further, that India had, at one time, produced a sophisticated culture comparable to Europe’s classical past.

Jones’ work helped trigger a wave of romantic “Indomania” which imagined India to be the source of civilization (See this post for some related discussion). His non-legalistic translations also helped transform European attitudes about Indian culture and literature. His translation of Kālidāsas’ play, Śakuntalā (published in 1789) received widespread and rapturous attention across Europe, particularly in Germany – it was an influence on both Goethe and Schlegel, for example. The same year, he also produced a translation of Jayadeva’s Gītagovinda, which remarkably little bowdlerization, given the eroticism of the original text, which impressed German Romanticists such as Herder greatly.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Jones was critical of the notion that contemporary India was but a shadow of an almost forgotten golden age of monotheistic purity. Between 1784 and 1789 Jones also wrote a series of “hymns” to Hindu deities such as ‘Camdeo’ (Kama) and ‘Durgá’. Again, these poems were widely circulated and praised by European readers, although some reviewers worried that Jones had ‘gone native’. For an Englishman to compose a hymn of praise to an Indian deity was, at that time, quite a radical act. His ideas about poetry, particularly the creative power of imagination (see, for example, his “On the Poetry of Eastern Nations” 1772) were a tremendous influence on the Romantic Movement.

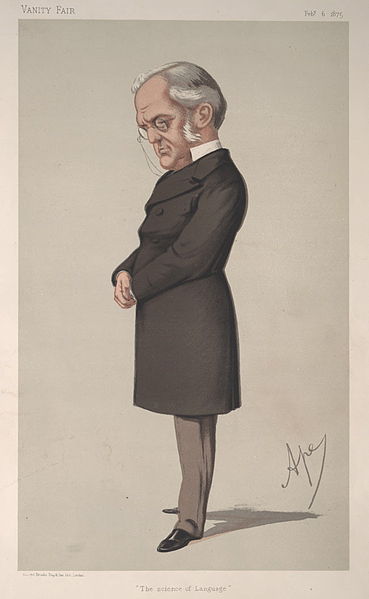

Max Müller

Friedrich Max Müller (1823-1900) is mainly remembered for his editing of the 50-volume series Sacred Books of the East. Born in the town of Dessau, he studied Sanskrit in Berlin and Paris, he moved to Oxford in 1846 where he undertook a translation of the Rg Veda. 3 He was appointed Professor of Modern European Languages at Oxford University, then later occupied the Chair of Comparative Philology. Although Jones’ work was the underpinning of much of Müller’s research, he modified it considerably, and his work on the Rg Veda introduced him to the “Aryas” – identified as nomadic pastoralists who migrated into Northern India from Central Asia, demonstrating for Müller that the Rg Veda was the most ancient source for the shared Indian and European past. It was Müller who coined the terms “Henotheism” (the worship of single gods) and “Kathenotheism” (the worship of one god after another). Müller’s hope was that in making a new edition of the Veda available to western-Educated Hindus, they would be able to reform their culture and resurrect the glories of their lost past (helped in this noble enterprise by the British, naturally). Müller was one of the most celebrated intellectuals of his day; a frequent contributor to popular journals such as Blackwood’s Magazine and The Nineteenth Century (in which he crossed swords with Theosophist A.P. Sinnett over the term ‘esoteric Buddhism’), and a sought-after lecturer – transcripts of which were often pirated before their official publication. He was also friendly with Colonel Olcott, although generally dismissive of Theosophy.

By the time Müller arrived on the scene, attitudes to Indian culture had changed markedly in Britain, largely thanks to Charles Grant and James Mill (see this post for a discussion of both). Indeed, by 1853, Śakuntalā was judged to be a work of ‘the greatest immorality and impurity’ and so unfit for study in Indian schools 4 Indophobia, had, to a large extent, replaced Indomania.

Like Jones before him, Müller believed that Europeans and Indians are related, rather than distant to each other, and this is where the term “Aryan” comes creeping in – in fact, Müller is generally credited with popularising the term. In 1847, Müller gave a lecture before the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Oxford (a prestigious event, Prince Albert being in attendance) in which he developed the theory that India was once home to two peoples; a light-skinned Caucasian race and a darker-skinned, more savage race. The lighter-skinned race is of course the Aryans, a vigorous warrior-people who vanquished and subjugated the dark-skinned savages. This “glorious work of civilisation” as Müller puts it, is being continued (in India) by the English descendants of those Aryans. For Müller, the Aryans represented a kind of golden age of India – a state of grace from which modern India had sadly fallen into idolatry and “a groveling worship of cows and monkeys.”

Müller, in later life, recanted his earlier views and was sharply critical of the twinning of Aryan with a racial, as opposed to a linguistic category: “We challenge the seeming stranger, and whether he answer with the lips of a Greek, a German, or an Indian, we recognize him as one of ourselves. Though the … physiologist may doubt,… all must yield before the facts furnished by language.” He frequently spoke out against the routine denigration of Indians by the British, and maintained that Indians were brothers to Europeans “in both language and thought.” 5

Müller’s theory of an Aryan kinship between Indians and Europeans was not universally accepted. There was considerable resistance to the idea from those who could not countenance any relation between India and Europe (be it language, culture or religion) and from the exponents of race science. Indophobia also intensified after the Great Rebellion of 1857. But more about that in the next part of this series.

Sources

Tony Ballantyne, Orientalism and Race: Aryanism in the British Empire (Palgrave, 2002)

Michael J. Franklin, Orientalist Jones: Sir William Jones, Poet, Lawyer and Linguist, 1746-1794 (Oxford University Press, 2011)

Arie L Molendijk, Friedrich Max Müller & The Sacred Books of the East (Oxford University Press, 2016)

Sharada Sugirtharajah, Imagining Hinduism: A Postcolonial Perspective (Routledge, 2003)

Thomas R. Trautmann, Aryans and British India (University of California Press, 1997)

Notes: