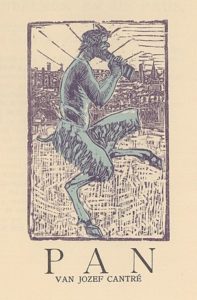

Pan: the unformed Pan in DH Lawrence’s animist vision – II

“The collective problem, then, is to institute, find, or recover a maximum of connections. For connections (and disjunctions) are nothing other than the physics of relations, the cosmos. Even disjunction is physical, like two banks that permit the passage of flows, or their alternation. But we, we live at the very most in a “logic” of relations. We turn disjunction into an “either/or. ” We turn connection into a relation of cause and effect or a principle of consequence. We abstract a reflection from the physical world of flows, a bloodless double made up of subjects, objects, predicates, and logical relations.

Gilles Deleuze, Essays Critical and Medical (1997)

Continuing from the previous post in this series, here are some further explorations of D.H. Lawrence’s animist vision of Pan. Again, the main texts I’ll be drawing from are the novella St. Mawr and the essay Pan in America. Both the essay and St. Mawr were conceived in 1924, when Lawrence was living in New Mexico.

I left off my thoughts on the Pan-theme in St. Mawr with a brief examination of the after-dinner conversation in which Pan is discussed. Shortly after that, there is an exchange between Lou and her mother which underscores a key Lawrencian theme – the relationship between men and women, and how modernity has fractured normal relations between the sexes.

“Louise!” said Mrs. Witt at bed-time. “Come into my room for a moment, I want to ask you something.”

“What is it, mother?”

“You, you get something from what Mr. Cartwright said about seeing Pan with the third eye? Seeing Pan in something?”

Mrs. Witt came rather close and tilted her face with strange insinuating question at her daughter.

“I think I do, mother.”

“In what?”–The question came as a pistol-shot.

“I think, mother,” said Lou reluctantly, “in St. Mawr.”

“In a horse!”–Mrs. Witt contracted her eyes slightly. “Yes, I can see that. I know what you mean. It is in St. Mawr. It is! But in St. Mawr it makes me afraid–” she dragged out the word. Then she came a step closer. “But, Louise, did you ever see it in a man?”

“What, mother?”

“Pan. Did you ever see Pan in a man, as you see Pan in St. Mawr?”

Louise hesitated. “No, mother, I don’t think I did. When I look at men with my third eye, as you call it–I think I see–mostly–a sort of–pancake.”

She uttered the last word with a despairing grin, not knowing quite what to say.

“Oh, Louise, isn’t that it! Doesn’t one always see a pancake! Now listen, Louise. Have you ever been in love?”

“Yes, as far as I understand it.” “Listen, now. Did you ever see Pan in the man you loved? Tell me if you did.”

“As I see Pan in St. Mawr?–no, mother!” And suddenly her lips began to tremble and the tears came to her eyes.”

In St. Mawr the world of men – exemplified by Lou’s husband Rico, has lost the fire of the unformed Pan. They are domesticated and tamed. Rico is clearly a dandy – he is “perpetually presentable”, selfish and attention-seeking – “like Adonis waiting to be persuaded not to die.” Lou also – ironically – identifies her husband with Priapus: “The world always was a queer place. It’s a very queer one when Rico is the god Priapus. He would go round the orchard painting life-like apples on the trees, and inviting nymphs to come and eat them. And the nymphs would pretend they were real: ‘Why, Sir Prippy, what stunningly naughty apples!’ There’s nothing so artificial as sinning nowadays. I suppose it once was real.” Rico’s refusal of sexuality is mirrored by St. Mawr’s refusal to mount the English mares (see previous post).

Similarly, Lou’s mother, Mrs. Witt, finds herself unimpressed with the modern examples of manhood, and becomes infatuated with St. Mawr’s Welsh groom, Lewis. It seems to her sometimes that Lewis is himself part of the horse – wild and untameable. She asks him to marry her, but he refuses her – he cannot be tamed or civilised.

Is there is an implicit refusal of compulsory heteronormativity here? It seems to me that transgression, in Lawrence’s writing, is the prelude to redemption – if only temporarily. St. Mawr, as the emissary of Pan-consciousness, and the wild landscape of the end of the novella both embody a vitality and awe-fulness that surpasses human relations. Queer themes do erupt in Lawrence’s work from time to time (for example, The Prussian Officer and Women in Love). In their varied relations to the wild, the two women, the groom Lewis and St. Mawr the horse-Pan all suggest that they are of a world where the norms and codes of modern life do not apply. Lou’s husband Rico, in his fantasies of becoming a great artist and his refusal to risk himself represents the failure of such an impulse. Moreover, Lawrence must surely have been aware that Pan is sometimes called duserös – “unlucky in love” and that his sexual pursuits are frequently unsuccessful.

Lou’s husband Rico is maimed when out riding St. Mawr. The horse shies and is pulled down by Rico, and Lou sees – with a hallucinatory clarity of vision – the horse on the ground:

” a pale gold belly, and hoofs that worked and flashed in the air, and St. Mawr writhing, straining his head terrifically upwards, his great eyes starting from the naked lines of his nose. With a great neck arching cruelly from the ground, he was pulling frantically at the reins, which Rico still held tight.”

Later, Rico demands that Lou has the horse shot, and various English characters support the view that the horse is evil, and if not shot, should be gelded. Lou’s answer to this is: “”I should say: ‘Miss Manby, you may have my husband, but not my horse. My husband won’t need emasculating, and my horse I won’t have you meddle, with. I’ll preserve one last male thing in the museum of this world, if I can.'”

Lou decides to return to America with her mother, taking with them the horse, and the grooms Phoenix and Lewis. St. Mawr is a gateway – an impetus or herald that allows Lou to move out of the intolerable confines of her loveless marriage to Rico and their stultified life in England to a new, full vital existence in America. In her movement to America, St. Mawr recedes into the background – mission accomplished. Lou moves to New Mexico, and finds that the vital, fiery existence she sensed through St. Mawr is in the land itself. The “mysterious fire of the horse’s body” becomes the “latent fire of the vast landscape”. Like the horse, the ranch and landscape are both splendid and terrible:

“There’s something else for me, mother. There’s something else that even loves me and wants me. I can’t tell you what it is. It’s a spirit. And it’s here, on this ranch. It’s here. in this landscape. It’s something more real to me than men are, and it soothes me, and it holds me up. I don’t know what it is, definitely. It’s something wild that will hurt me sometimes and will wear me down sometimes. I know it. But it’s something big, bigger than men, bigger than people, bigger than religion.”

Both Lou and her mother escape from the limits of modernity into the wild landscape of New Mexico.

“He was Pan. All: what you see when you see in full.”

Lawrence’s unformed Pan is that of a direct, unconscious and unobstructed relation to a living universe. A similar sentiment is expressed in William S. Burroughs’ Apocalypse:

“”When art leaves the frame and the written word leaves the page – not merely the physical frame and page, but the frames and pages of assigned categories – a basic disruption of reality itself occurs: the literal realization of art. Success will write Apocalypse across the sky. … The final Apocalypse is when every man sees what he sees, feels what he feels, and hears what he hears. The creatures of all your dreams and nightmares are right here, right now, solid as they ever were or ever will be.”

Both Burroughs and Lawrence recognise that it is the over-reliance upon abstraction that causes the death of Pan. Not just the dry, mechanistic universe of technology, but the Cartesian divide between manipulating mind and inert nature. Rather, the sense of Pan emerges out a wholeness, exemplified in Pan in America by the encounter of the great tree:

“The tree gathers up earth-power from the dark bowels of the earth, and a roaming sky-glitter from above. And all unto itself, which is a tree, woody, enormous, slow but unyielding with life, bristling with acquisitive energy, obscurely radiating some of its great strength. It vibrates its presence onto my soul, and I am with Pan. I think no man could live near a pine tree and remain suave and supple and compliant. Something fierce and bristling is communicated. The piny sweetness is rousing and defiant, like turpentine, the noise of the needles is keen with æons of sharpness. In the valleys of wind from the western desert, the tree hisses and resists. It does not lean eastward at all. It resists with a vast force of resistance, from within itself, and its column is a ribbed, magnificent assertion.”

Despite the essay’s apparent romanticism, Pan in America is neither escapism nor the familiar trope of self-discovery through “natural” encounters; rather it is a call to recognise that the everything in the physical world of which humanity is merely one element has agency, power and vitality. When he writes, “You have to abandon the conquest, before Pan will live again. You have to live to live, not to conquer. What’s the good of conquering even the North Pole, if after the conquest you’ve nothing left but an inert fact? Better leave it a mystery” – it is an invitation to re-examine the world with refreshed senses; to recover the mystery and wonder that is all around us. Yet at the same time, Lawrence is warning that to inhabit such a world is to court danger and accept risk:

“Thus, always aware, always watchful, subtly poising himself in the world of Pan, among the powers of the living universe, he sustains his life and is sustained. There is no boredom, because everything is alive and active, and danger is inherent in all movement. The contact between all things is keen and wary: for wariness is also a sort of reverence, or respect. And nothing, in the world of Pan, may be taken for granted.”

Sources

Ria Banerjee The Search for Pan: Difference and Morality in D.H. Lawrence’s “St. Mawr” and “The Woman Who Rode Away”. D.H. Lawrence Review. 37.1 (2012) pp65-89

Gilles Deleuze. Essays Critical and Medical. trans. Daniel W. Smith and Michael A. Greco (University of Minnesota Press 1997)

Jeffrey Mathes Mccarthy. Green Modernism: Nature and the English Novel, 1900-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2015)

Patricia Merivale Pan the Goat-God: His Myth in Modern Times (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1969.

Fambrough, Preston. “THE SEXUAL LANDSCAPE OF D. H. LAWRENCE’S “THE PRINCESS”.” CLA Journal 53, no. 3 (2010): 286-301. Accessed April 15, 2021. www.jstor.org/stable/44325643

William S. Burroughs

Apocalypse (video)

by D. H. Lawrence

St. Mawr

The Woman who Rode Away and other stories

Collected Short Stories

Pan in America

2 comments

Cheryl Essary

Posted April 24th 2021 at 3:08 pm | Permalink

Shocked, thrilled, amazed – to see not only DH Lawrence recognized, but the one piece of his that has stuck with me for over 40 years – St Mawr. I read it first when I was in my twenties and its comparison of the ‘masculinity’ between the horse and men struck a chord with me. This was long before I studied occultism, the gods, or knew anything at all about Pan. I recently re-read it (at age 61) and it was even more impressive and relevant to me with what I have learned and experienced. I treasure this novella and love that it’s been recognized. As a woman I relate to it as I have so little else that I read. Thank you for these two essays, you have completely made my day.

Bbbarry

Posted April 24th 2021 at 6:12 pm | Permalink

Grand, Phil; a great couple of essays. With you all the way! Thanks for your efforts.