Pan: Adolescent Panics in Forster and Saki

“God went out (oddly enough with cricket and beer) and Pan came in.In a hundred novels his cloven hoof left its imprint on the sward; poets saw him lurking in the twilight on London commons, and literary ladies in Surrey, nymphs of an industrial age, mysteriously surrendered their virginity to his rough embrace.”

Somerset Maugham, quoted in Hutton, Triumph of the Moon, p48

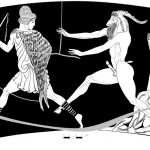

For this post, I’m taking a cue from Patricia Merivale’s Pan the Goat-God: His Myth in Modern Times (Harvard Univ. Press, 1969). Merivale’s book is particularly useful as she focuses on the great upswell of appearences of Pan in English prose between 1890 and 1918. Literary representations of Pan in the fin de siècle change dramatically, from Pan as an essentially benevolent and transcendental figure, to a much darker character. Whereas Romantics such as Wordsworth or Keats, who wrote in Endymion “Pan will bid us live in peace, in love and peace among his forest wilderness” tended to view Pan as a somewhat disembodied spirit of nature, reflecting a general nostalgic yearning for nature; the Pan which emerges in the late Victorian period was morally ambivalent, wild and dangerous, as can be seen in the work of writers such as Arthur Machen, Algernon Blackwood, Somerset Maugham, and D.H Lawrence.

“The paradox of being half goat and half god,” Merrivale remarks “is at the very core of his nature” – and she goes on to point out that Pan is a liminal figure, straddling both the vision of “universal, transcendental Nature” and the instinctual forces of the psyche which are rooted in – and draw us towards the primeval sensibility which exists at the margins of civilisation. Pan represents, in the words of Aldous Huxley “the dark presence of the otherness that lies beyond the boundaries of man’s conscious mind”. This vision of Pan as a ever-lurking presence, waiting to perturb and confound our conscious, rational and ordered life is a strong theme in Pan-related fiction. Moreover, for a number of nineteenth and early-twentieth century authors who were homosexual and classically educated, Pan became a key figure in a vision where male beauty and desire is recognised and permitted, rather than outlawed. As Sandie Byrne (2007) notes, Victorian and Edwardian literary homoeroticism frequently drew on Classical mythology as a register or code.

I’m going to briefly discuss two literary treatments which I think articulate this theme – E.M Forster’s The Story of a Panic (1902) and Saki’s (aka H.H Munro) Gabriel-Ernest (1910).

The Story of a Panic

Mr. Tytler, the narrator of The Story of a Panic is very much the convention-bound Englishman, staying in an Italian hotel with his two daughters. The other guests are Mr Sandbach – a retired clergyman, Mr. Leyland – an artist, and the Misses Robinson, and their nephew, Eustace, who the narrator describes as being “odious”, “peevish” and “unhealthy”. Eustace, much to the disgust of the narrator, displays an un-English avoidance of healthy pursuits such as swimming; nor is he studious – rather, he prefers “lounging” – “His aunts thought him delicate; what he really needed was discipline.” Whilst the adults discuss the picturesque, Eustace cuts a piece of wood and makes a whistle (a Pan pipe). The adults lament that “All the poetry is going from Nature … the mere thought that a tree is convertible into cash is disgusting”. The artist Leyland complains that “the woods no longer give shelter to Pan” which prompts Sandbach to proclaim that “Pan is dead.” He relates the story of Pan’s death (as told by Plutarch and Eusebius). Suddenly, the party is disturbed by the onset of a wind – perhaps prompted by Eustace blowing his whistle – which provokes in them “brutal, overmastering, physical fear, stopping up the ears, and dropping clouds before the eyes, and filling the mouth with foul tastes”. The party flees the scene, and, realising that Eustace is missing, return to find him lying on the ground, hands “convulsively entwined in the long grass,” a “peculiar smile” on his face and nearby, “some goat’s footmarks in the moist earth beneath the trees”. Sandbach exclaims that “The Evil One has been very near us in bodily form”. The adults agree to say nothing about this peculiar event, but Eustace begins to behave oddly. He shows an unseemly interest in the whereabouts of a waiter at the hotel named Gennaro – “a clumsy impertinent fisherlad”. He runs around the wood and reappears with a dazed hare in his arms. He spontaneously kisses an old Italian peasant woman and offers her flowers. The narrator finds such “promiscuous intimacy … perfectly intolerable.”

At the hotel, Eustace eagerly embraces Gennaro. The adults come to the conclusion that Eustace is mad and will require watching. That night, the narrator wakes to find Eustace outside the hotel, clad in his nightshirt, dancing and “blessing the great forces and manifestations of Nature”. One of the narrator’s daughters, perhaps recognising that there is a bond between Gennaro and Eustace, prompts him to enlist Gennaro in recapturing Eustace. The two boys meet, but their bonding of brotherhood is interrupted by the narrator, who offers Gennaro a ten lira note. Gennaro reaches for the money, but Eustace grips his hand. As Eustace and Gennaro share confidences, the adults close in and drag Eustace away to his room. Gennaro avers that Eustace will die if he is confined to his room. Gennaro frees Eustace, and together, they jump from the hotel window. Eustace runs off into the night, never to return, and Gennaro cries out “He has understood and he is saved … instead of dying he will live!” Gennaro, when later confronted by the narrator who wants his money returned, promptly falls down dead, overcome with remorse for his part in the attempt to confine Eustace. The story ends with the departing sounds of Eustace’s exultations far down the valley, in which “still resounded the shouts and laughter of the escaping boy.”

The Story of a Panic is a thinly-cloaked tale of sexual awakening, and by drawing on the figure of Pan, Forster is able to point to the encounter with an erotic “other” – an encounter which is both appealing, threatening and transformative. An awakening to a polymorphous pleasure which is sudden, powerful and disruptive – Eustace’s transformation – and in particular, his intimate friendship with Gennaro, with its blurring of class boundaries, threatens the English notion of proper behaviour and decorum. When the story was published in 1904, Charles Sayle, the Cambridge librarian interpreted it to Maynard Keynes as being basically about “buggery” – an interpretation that Forster insisted that he had been initially unconscious of.

Gabriel-Ernest

Saki’s Gabriel-Ernest is the tale of a boy with savage propensities – a “wild, nude animal” who is introduced into a “primly ordered house”, with disasterous consequences. Beginning with the remark by an artistic friend “There is a wild beast in your woods”, narrator Van Cheele, finds

“On a shelf of smooth stone overhanging a deep pool in the hollow of an oak coppice a boy of about sixteen lay asprawl, drying his wet brown limbs luxuriously in the sun. His wet hair, parted by a recent dive, lay close to his head, and his light-brown eyes, so light that there was a tigerish gleam in them, were turned towards Van Cheele with a certain lazy watchfulness. It was an unexpected apparition, and Van Cheele found himself engaged in the novel process of thinking before he spoke. Where on earth could the wild-looking boy hail from?”

When questioned as to his eating habits, this alarming apparition replies “…rabbits, wild-fowl, hares, poultry, lambs in their season, children when I can get any; they’re usually too well locked in at night when I do most of my hunting. It’s quite two months since I tasted child-flesh.”

The day after this encounter, Van Cheele, much to his alarm, finds

“Gracefully asprawal on the ottoman, in an attitude of almost exaggerated repose, was the boy of the woods. He was drier than when Van Cheele had last seen him, but no other alteration was noticeable in his toilet. Van Cheele’s aunt enters at that point, and he explains the boy’s presence as “a poor boy who has lost his way – and lost his memory.” Miss Van Cheele rises to the occasion with the proper concern for a “naked homeless child” and finds him “sweet”. “We must call him something till we know who he really is,” she said. “Gabriel-Ernest, I think; those are nice suitable names.”

Van Cheel agreed, but he privately doubted whether they were being grafted onto a nice suitable child.

Later, Van Cheele’s artistic friend Cunningham describes his initial encounter with Gabriel-Ernest.

“Suddenly I became aware of a naked boy, a bather from some neighbouring pool, I took him to be, who was standing out on the bare hillside also watching the sunset. His pose was so suggestive of some wild faun of Pagan myth that I instantly wanted to engage him as a model, and in another moment I think I should have hailed him. But just then the sun dipped out of view, and all the orange and pink slid out of the landscape, leaving it cold and grey. And at the same moment an astounding thing happened – the boy vanished too!”

“What! Vanished away into nothing?” asked Van Cheele excitedly.

“No; that is the dreadful part of it,” answered the artist; “on the open hillside where the boy had been standing a second ago, stood a large wolf, blackish in colour, with gleaming fangs and cruel, yellow eyes.”

The story climaxes as Van Cheele realises that Gabriel-Ernest is a werewolf, only to find that he has taken a small child home from Sunday school. Van Cheele vainly pursues them, but both disappear as the sun sets, although Gabriel-Ernest’s clothes are later found lying in the road. it is assumed that the child fell into the nearby river, and that Gabriel-Ernest drowned trying to save it. Miss Van Cheele sets up a memorial “to Gabriel-Ernest, an unknown boy who bravely sacrificed his life for another.

“Van Cheele gave way to his aunt in most things, but he flatly refused to subscribe to the Gabriel-Ernest memorial.”

Gabriel-Ernest not only foregrounds the tension between desire and repression, but also the instrusion of the fantastic and the perverse into the ordered realm of the normal. Although the story often veers towards the camp, it is one of the most obviously sensual of Saki’s tales. Gabriel-Ernest, although described in a similar fashion to the other languid youths of Saki’s tales (such as Reginald or Clovis) he is decidedly feral – as Sandie Byrne comments:

“The wild in Saki’s stories is beautiful but violent and dangerous. It contains no trace of the myths of Nature as nurturing Mother. The supernatural force of the wilderness is associated with the beauty of an animal or a lovely, wild boy. The object of desire in in Saki’s stories is often adolescent and inhuman, or at least outside human society, and therefore constraints of class, manners, and mores.” (2007, p115)

More than one reviewer has noted the similarity between Gabriel-Ernest and Wilde’s Importance of Being Ernest. There are also echoes of Kipling’s In the Rukh (1893) in which an English forester named Gisborne encounters a man, Mowgli, who has been raised by wolves and is accompanied by four wolves. In their first encounter, Mowgli is “crowned with flowers, playing upon a rude bamboo flute,” around whom the wolves dance on their hind legs. Gisborne’s German superior names Mowgli as “Faunus”. Saki made more obvious – and crueler – use of Pan in his story, The Music on the Hill in which a stag gores to death a woman who has “persuaded” an otherwise contented bachelor to marry her. Mr Tytler is disgusted and disturbed by his experience, whilst Van Cheele, though seemingly unwilling to accept the obvious, is more ambivalent in his interest.

Both of these stories share similar devices – both are recounted from the perspective of a male narrator bound up in convention and propriety, with the female presence of well-intentioned but uncomprehending maiden aunts. Both narrators’ lack of imagination serve to heighten the extraordinary events which are beyond their comprehension. Both highlight the threat and appeal of male-to-male desire through the body of an adolescent characterised as wild and languid. Both Eustace’s wild behaviour and Gabriel-Ernest’s wild appearance and speech foreground the threatened intrusion of untameable nature/desire into the conventional spaces of English middle-class life.

Between the late 1890s and the First World War, “adolescence” became a key interest for educationalists and psychologists. Adolescent boys were frequently portrayed as being blindly led by their “biological urges” and lacking morality, ideals or individual volition. Some authorities, edging towards moral panic, insisted that if not disciplined and controlled rigorously, adolescent boys would become wayward and lead to national degeneration. The American Stanley Hall for example, is credited with having “discovered” adolescence, and his 1905 work proposed a theory of adolescence followed a Darwinian evolutionist ideal in which the stages of infancy, childhood, and adolescence are primitive stages of development prior to attaining fully developed adulthood. Boys were superior to girls in this evolutionary scheme. Hall reccomended that adolescents be controlled by the state and its agencies, and be taught self-control, and that young women be trained to regard marriage as their “one legitimate province”.

Martha Vicinus (in Dellamora, 1999) argues that in late Victorian culture, adolescent males came to embody “a fleeting moment of liberty and of dangerously attractive innocence, making possible fantasies of total contingency and total annihilation … the boy became a vessel into which an author – and a reader – could pour his or her anxieties, fantasies, and sexual desires.” (pp83-84) She argues that the turn to Classical mythology not only alerted aware readers to implicit sexual messages, but that figures such as Pan, Diana, Apollo and Antinous represented not only freedom, but a “spiritualized disdain” for the age’s materialism and industrial modernity and the expression of the intensity of a single moment of perfection or creativity. Nature becomes associated with creativity and freedom, rather than fertility and the “sanctioned cycle” of courtship, marriage, and raising a family. Vicinus describes how late Victorian fiction was concerned with themes of “manly love” – often set in homosocial environments such as the public school – valorised devoted friendships and self-sacrifice. The association of adolescent protagonists with Pan or Puck raises them to a mythic status, removing them from the world of normal relations – signifying both the possibility of lost innocence in the face of rampant modernity, the possibility of regeneration and autonomous freedom, if only fleetingly.

Needless to say, such homoerotic outings for Pan seem to have completely passed unnoticed by Pagan treatments of Pan until fairly recently. Pagan authors in the 1970s-80s, if they mentioned Pan at all other than as an aspect of the archetypal “Horned God” were more likely to cite Kenneth Grahame’s bucolic portrayal of Pan from The Wind in the Willows or that of Dion Fortune (The Goat-Foot God). Occasionally there were asides in the direction of Crowley’s Hymn to Pan but without any reference to the ‘specifics’ of Crowley’s relationship to Victor Neuberg. Amidst vague mention of Pan representing uninhibited ‘natural’ sexuality; the Wiccan Pan of this era was represented very much in terms of fertility and the companion of the Goddess.

Further Reading

David Bradshaw (ed) The Cambridge Companion to E.M Forster (Cambridge University Press, 2007)

Sandie Byrne, The Unbearable Saki: The Work of H.H Munro (Oxford University Press, reprint edn 2007)

Richard Dellamora Victorian Sexual Dissidence (University of Chicago Press, 1999)

R.K Martin, G Piggford (eds) Queer Forster (University of Chicago Press, 1997)

Patricia Merivale, Pan the Goat-God: His Myth in Modern Times (Harvard Univ. Press, 1969)