Pan: A Clergyman’s Redemption in Margery Lawrence’s How Pan Came to Little Ingleton

‘Oh great god Pan, I know Thee! – I thank Thee – I bless Thee . . . Thee and all Thy People great and small – for indeed, indeed beneath the mantle of the God whose name is Love, is there not room for all in His world to shelter?’

I’ve only recently begun to read the magical fiction of Margery Lawrence (1889-1969), and admittedly, am wondering why I have never encountered her before, as the more I read about her, the more fascinating she sounds. A prolific author, she wrote over thirty novels and short story collections. Curiously though, there seems to be a dearth of critical scholarship analyzing her work.

I have yet to find a full biography of Lawrence, but here’s what I’ve managed to cobble together from various sources.

Margery Lawrence studied art in London and France, and seems to have traveled widely throughout Europe, and living for a while in Monte Carlo and Jamaica. She spent some of the First World War in Italy, where she had a romance with an Italian soldier and was arrested twice by the Italian authorities – once under the suspicion that she was a Romanian spy!

She began writing novels in the 1920s – beginning with adventure stories and romance novels. Her first novel – Miss Brandt, Adventuress (1923) is about a high society adventuress and jewel thief. Two of her novels – Red Heels (1924) and The Madonna of Seven Moons (1933) were made into films. Red Heels was the basis for Das Spielzeug von Paris – ‘The Toy of Paris’ (1925), directed by Michael Kertész, one of the most prolific film directors of the twentieth century. The novel is the story of Célimène, a French dancer who has caught the eye of an English diplomat, but eventually spurns his attentions and returns to her former lover and her life in the revue theatres of Paris. The Madonna of Seven Moons was released by the British film company Gainsborough Pictures in 1945, starring Phyllis Calvert & Stewart Granger, and was one of the most popular films of the period. The film revolves around the respectable and repressed Italian Maddalena Labardi (played by Phyllis Calvert) who is haunted by her memories of being sexually assaulted as a teenager. She suffers from spells of amnesia and takes on a second identity of Rosanna, the free-spirited lover of a jewel thief, Nino (played by Stewart Grainger).

Strong female characters are a constant theme throughout Lawrence’s fiction. The publication of her 1928 novel Bohemian Glass was delayed due to the publisher’s concern over its risqué subject– the lives of young artists in Chelsea.

In 1929, Lawrence wrote an essay for Cosmopolitan entitled “I Don’t Want to Be a Mother”. When an advert for the piece was run in Good Housekeeping magazine, the editors published a disclaimer, stating that they supported Lawrence’s right to express her opinions, but did not endorse them. As Daniel Delis Hill points out, for Lawrence to express such an opinion was scandalous, to say the least. 1 Lawrence never was a mother, but in 1938 she married Arthur Edward Towle and resided in London with him until his death in 1948.

Lawrence also wrote ghost and horror stories beginning in the 1920s, which were published in periodicals such as The Tatler and pulp magazines such as Hutchinson’s Adventure-Story Magazine and Mystery-Story. Three collections of these stories were published – Nights of the Round Table (1926), Terraces of Night (1932), and The Floating Café (1936). Lawrence described herself as a “ghost-hunter”. She was a member of The Ghost Club, and in her foreword to R. Thurston Hopkins’ Ghosts Over England (1953) remarks on her participation in the ‘clearings’ of many haunted houses. 2. An ardent Spiritualist, several of her later novels focus on Spiritualist themes, among them being Madame Holle (1934), The Bridge of Wonder (1939), and The Rent in the Veil (1951). She also contributed to the ‘psychic detective’ genre with the character of Dr. Miles Pennoyer, a psychic physician who solves mysterious events with the aid of ghostly allies, and has acquired mystical abilities through traveling to the Far East (Lawrence credits both Algernon Blackwood’s John Silence and Dion Fortune’s Dr. Taverner as inspirations for Pennoyer). Pennoyer’s adventures appeared in Number Seven Queer Street (1945) and Master of Shadows (1959). One of her last novels, The Tomorrow of Yesterday (1966) concerns the history of a utopian civilization on the planet Mars, which is destroyed through reckless science and power struggles. The last surviving Martians decamp to Earth where they guide the development of the human race. In her introduction, Lawrence says that the narrative was dictated by its Martian author through a trance medium. Bride of Darkness (1967) features a man who unwittingly marries a powerful witch and practitioner of black magic.

In addition to her fiction, Lawrence also edited a collection of true stories of the supernatural entitled Fifty Strangest Stories Ever Told (1937) and a ‘primer’ of Spiritualism, Ferry Over Jordan (1944). In Ferry Over Jordan, Lawrence made the case for both life after death and reincarnation, expressing her belief that she had past lives in Egypt, Ancient Greece, and Persia. In support of her argument, she referenced Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the Egyptologist Grafton Elliot Smith, and Bligh Bond, whose excavations at Glastonbury were assisted by a medium.

But what of Pan? As far as I am aware, the only story of Lawrence’s in which Pan makes a direct appearance is How Pan Came to Little Ingleton (1926). It bears some resemblance to Lord Dunsany’s 1927 novella The Blessing of Pan (see this post) insofar as the central character is a clergyman who is disturbed by an intrusion of the uncanny into a sleepy English village. The protagonist – the Reverend Thomas Minchin is a clergyman of rather stern disposition. He is a teetotaller, celibate, and a non-smoker. In his efforts to promote piety in Little Ingleton, he has banned dancing in the village hall and green; restricted the sale of beverages apart from ginger ale, closed down the village pub, and banished from the chemist’s shop ‘snares of the devil’ such as scent and lip rouge. He evinces contempt for his predecessor, old Father Fagan, who has let Little Ingleton slide into ‘idle happiness’ and even took part in village dances.

Finding the schoolhouse empty – and on a Sunday, no less – Reverend Minchin is searching for the schoolmistress, Miss Rosamond Perkins, and decides that – in contradiction to his stern injunctions – she has taken the children out into the woods ‘to play with God in His lovely world’ as she put it to him on a previous occasion. He looks for her cottage, called ‘Rose Nook’, which she has told him, he suddenly remembers, is ‘Just round the corner of Pan’s Lane’, and recalls that the local squire had told him that the nearest town, King’s Panton, derives its name from ‘Kynge Pan hys towne’. Mr Minchin is pleased that all signs of paganism have been swept away by modernity.

Preoccupied with the intention of speaking sternly to Miss Perkins, and dragging the children back to the schoolhouse to study their Bibles, Reverend Minchin trips over an obstacle in the road – which turns out to be a shabbily-dressed young man who was sitting in the road. A curious conversation ensues between Minchin and the young man, who the Reverend takes to be a vagabond.

“The stranger twinkled again, quite unimpressed.

‘I can see you are a clergyman all right – is that what you call a man of God?’

Mr Minchin was outraged.

‘Sir! Are you not a Christian, that you ask me such a question?’

The stranger threw a last handful of crumbs to the waiting squirrel, and clasping his hands round his dusty knees, surveyed Mr Minchin again. Then laughed, softly, oddly.

‘A Christian? I don’t think I’ve ever been asked that before!’

‘Then it’s quite time you were,’ said Mr Minchin virtuously.

‘Time – ah, there’s so much time, isn’t there?’ said the stranger, rather irrelevantly. ‘But to continue, O Man-of-God! What brings you wandering out here this Sunday afternoon – when presumably all Men-of-God should be herding their flocks willy-nilly into church?’

The faint flavour of insolence in the stranger’s tone, strangely matching his impertinent upflaming hair, stung Mr Minchin, and his response was severe.

‘I agree with you. But unfortunately . . . my Sunday School class did not appear, and I came out to find them . . .’

The young man, hunching his shoulders back against the warm red earth of the bank, laughed suddenly, amusedly: a gleeful spurt of laughter like the uprush of a spring to the sunlight.

‘So for once Pan won, eh? The old gods against the new – the lure of the sun and the hills and the blue, blue sky . . . ha, ha! Well, my worthy son of the Christian church, go on . . . so you came a-wandering to find your straying flock, eh?’

‘Er – yes . . .’ For the life of him the Reverend Thomas could not quite help an odd little feeling of trepidation under the fire of the yellow hawk’s eyes that watched him, and he finished lamely, ‘And I – er – wandered considerably further than I meant . . .’

‘You did indeed! . . .’ said the young man grimly.

There was a moment’s silence while he eyed the clergyman up and down, then down came the hooked nose again in a grin, and rolling over, he stretched for a shabby knapsack reposing against a giant root.

‘Down Pan’s Lane – into Panton Wood – over against Pan hys towne – and all on a Midsummer Day! Oh, wonderful – amazing – my poor dear earnest-minded friend!”

As the conversation continues, Reverend Minchin becomes increasingly alarmed, particularly when the young man says:

“I know God demands a certain amount of attention.’ His curious, half-wistful, half-insolent gaze strayed over the brooding hills, and he paused, then went on briskly – ‘but I fancy, you know, that God is a fair-minded Deity . . . and if folk come to worship Him on a Sunday morning, what harm is there if for the rest of the day they give worship to other gods – and maybe other gods than He?”

The young man also seems to know a good deal about Minchin’s attempts to ‘improve’ Little Ingleton.

‘. . . Didn’t you stop little Molly Isitt from wearing a pink sash? Tell the Squire that to start a cinema in the village meant encouraging immorality – since it would be held in the dark? Get Miss Banks’s maid, Ellen, sacked because you caught her kissing a gypsy in the lane? Abolish the kindly old custom of giving bread to beggars each Friday because it encouraged pauperism? Abolish beer-drinking and the use of perfumes? Forbid dancing and singing, and refuse permission for the yearly pageant to be held in the Vicarage grounds? . . .

All vanity – and turning their thoughts from the Lord,’ snuffled the Reverend Thomas feebly, for he was very frightened – above him the voice seemed to be shaping itself into a song of triumph and of scorn together, and he was shaking, cold, despite the glowing heat . . .

‘From the Lord! Oh Allah! Oh Set and Horus and Osiris! Oh Kali, Shiva, and all forgotten gods!’ Oh, the ringing scorn of that laughter – shrivelled tiny the wretched listener felt as the voice boomed on. ‘Oh Zeus, Apollo and goat-footed Pan! In the great world is there not room – is there not room for more than one God?’

The story breaks at that point then picks up again with the Reverend Minchin awakening from a prolonged sleep, and finds – somewhat to his amazement – that the Sunday church service has begun without him, and that the strange young man he met in the road earlier is delivering the sermon! The stranger speaks:

“of the grave eternal hills and of their story. Of the hills in whose cradling generous arms nestle grim Druid Grove and pagan altar – fairy ring and Christian church alike. Of the rains and dews that settle in their folds and run together into streams and pools, deep lakes and mighty rivers; of the little bright unconsidered flowers that grow on the hills, and the myriad unknown creatures that live out their coloured lives of but a day, the gossamer moths and lazy painted butterflies, the grey-velvet ground spider and his black neighbour the busy ant . . . Of the forgotten forts that, built by a long-dead people, still face the sea, the green turf weaving a winding sheet over the sturdy bones of the old builders; of the cromlechs and dolmens – the strange stone rings, so old that even their purpose is forgotten now – of the battered altars to ancient creeds, so old that their very names are dead; the green groves in hidden woodland places, groves planted in honour of goddesses that rule no longer . . .”

“he spoke of Others – of careless and happy things that roam the green woods in vivid lovely life, if not life as mere humans know it . . . of Those that knew and loved their Mother Earth ere ever Man had set foot upon it! Those Older Things that, retreating before Man and his noisy dusty cities, yet laugh and, shaking their wind-blown hair, withdraw deeper and deeper yet to their old fastnesses in mountain and cave and forest . . . Unbaptised, perchance – knowing no creed nor caste – merry pagan Things that own no church, yet should there not be room for all beneath the mantle of Him whose name is Love? . . . Room for even these, for elf and satyr and white-browed nymph, merry brown gnome and wandering fairy, fauns with their goat-feet, and green-eyed nixy with her dripping hair?”

Minchin is both moved and afraid of the feelings which the stranger’s sentiments stir within him. Turning to look at the congregation, he sees:

“As if in a dream from his place on the sloping bank above the path he watched the congregation file out, two and two, like the figures in a Noah’s Ark, a strung-out line of black shadows against the gorgeous sunset, rose, green and gold, singing jubilantly as they went – and smiled, without surprise, but with happy knowledge, as he saw, mingling with the village folk, Those of a different world, beast and satyr and elvish unnamed creature, all come to shout their gladness in one great festival of praise! He saw old Kitson, arm-in-arm with his wife . . . and a faun, goat-footed, leaf-crowned, pranced beside them and tweaked old Kitson’s hair . . . and the old man laughed and hugged his old wife the closer! He saw sour Gertrude Pring, who ran the post-office, companioned by two merry small Things, brown-eyed and saucy, and Miss Banks, unscandalised, walk beside a sly-eyed young Bacchante, whose white breasts gleamed shamelessly beautiful in the dusk . . .”

All of a sudden, as he is overwhelmed by feeling, it is as though a spell has broken and Reverend Minchin finds himself in the arms of Miss Perkins, and she preparing to kiss him. She believes, he discovers, that it was he who gave the wonderful sermon.

“Still dazed, but with his hand fast-locked in hers, Mr Minchin turned towards the listening hills, the dark woods that seemed to watch him, the dusk-filled valley from which he still vaguely thought came an echo of joyous singing . . . They had gone again back to Their secret places, these dear strange People who had turned aside to teach him wisdom, and his heart swelled within him in love and sorrow that he could not thank Them, bless Them, tell Them his humility, his deep-hearted gratitude!”

None of Reverend Minchin’s congregation know that it was Pan – and not he – that gave the sermon on that Midsummer’s eve, which has changed him forever.

“For since that marvellous hour of sight – when for a little while the veil before his eyes was torn away and he saw horned beast of the field, wilful elf and goblin, faun and nymph, mingling with village maid and man, jostle together singing prayer and praise in the Church of Christ, he has walked humbly, tremblingly before men, and in his gentleness and understanding, his loving-kindness and readiness to forgive sin, his old cruel bigotry is long forgotten.”

The story closes with a description of how Mr Minchin has re-instituted the Midsummer Feast in the village and makes his personal offering to “the Great God Pan, who, in a whimsy moment, came and played parson to save a parson’s soul.”

Sources

Melissa Edmundson Women’s Colonial Gothic Writing, 1850-1930: Haunted Empire (Palgrave Macmillan 2018)

Elisabetta Girelli Beauty and the Beast: Italianness in British Cinema (Intellect Books Ltd, 2009)

Daniel Delis Hill Advertising to the American Woman, 1900-1999 (Ohio State University Press, 2002)

Lisa Kröger and Melanie R. Anderson Monster, She Wrote: The Women who Pioneered Horror and Speculative Fiction (Quirk Books, 2019)

Amara Thornton Archaeologists in Print: Publishing for the People (UCL Press, 2018)

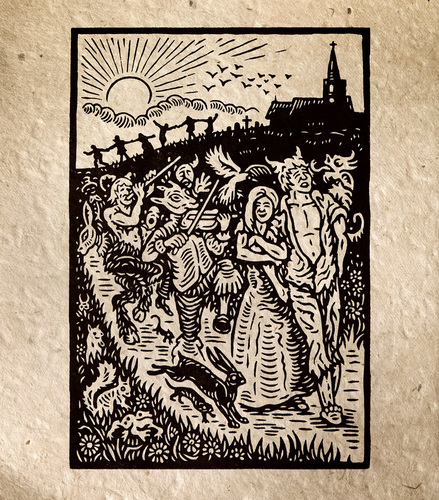

Richard Wells Damnable Tales: A Folk Horror Anthology (Unbound, 2021)

Online

Number Seven Queer Street – Margery Lawrence

With thanks to Richard Wells for kind permission to use his linoprint illustration for How Pan Came to Little Ingleton in the collection Damnable Tales: A Folk Horror Anthology. More of Richard’s artwork is available from his online shop.