One from the vaults: Occultism: A Postmodern Perspective

Other projects have turned me away from my usual writing schedule for enfolding, so this month, here’s an essay from “the vaults” (found on an old archive drive). Written in 1988 and no doubt dated, I still find points of relevance to contemporary occultism. I hope you do too.

“Our world is so crowded with marvels and miracles that they have become commonplace to us; especially when we no longer see ourselves as miracles. We swim through the world, deafened by the buzz of machines and the flicker of the Videodrome, our senses are dulled from the information overload. Yet, shifting to another position, we suddenly find that the world is magical.”

Living as we do, in a society that is rapidly mutating itself by means of computers, camcorders and cable TV; in which men can walk on the Moon, whilst others sell their children to the organ dealers; where the mysteries of life are probed during DNA manipulation and the realities of other people’s death served up on prime-time television, it is easy to wonder, where does ‘the occult’ fit in? Isn’t there enough fear and horror, beauty and wonder in this crazy old world of ours without looking into dark corners and ‘dabbling’ with the forbidden? In a world where political ‘isms’ have largely taken over the job of meat-grinding populations from religious ‘isms’, who needs more of the same? Isn’t the occult just a mess of half-baked psychobabble indulged in by those who need to justify their inadequacies, inequality, and intellectual shortcomings?

What is ‘the occult’ anyway? A quick flip through the dictionary tells us that the term refers to ‘secret’, ‘hidden’, or the supernatural, none of which helps too much. After all, our society is rotten with secrets; presumably, anyone who studies economics or political theory can be classed as studying ‘the occult’, since the workings of governments and multinationals rapidly lead you into areas that are truly ‘occult’. But no, that’s not how we usually think of the word. ‘Occult’ conjures up images of robed figures, or better yet, naked figures, cavorting in graveyards and behind closed doors; of wizened old men studying dusty books inside moldy libraries; teenagers dabbling with ouija boards and the novels of Clive Barker.

The subject of the ‘occult’ covers a vast range of subjects, from Alchemy to Zen, from spiritual speculation about the universe to bending cutlery. What formerly may have been ‘hidden’ is being increasingly brought into the neon glow of modern society; through books, films, videos, fanzines, and conventions, – all the extensions of the new mass communications media. Occult symbols abound on record sleeves, company logos, and designer fashion. In short, becoming another commodity. Occultists can no longer pretend that theirs is a specialist interest. It is another subculture; another fashion. Like any fashion, it moves through changes and fads. Like any fashion, you can buy into it and acquire a passing knowledge of its tacit beliefs, values, and assumptions. Like any other fashion, it provides its adherents with a sense of commonality, against other groups.

Occultism as a subject of inquiry is perhaps less interesting than the people whom it attracts. A great many people become involved in the occult not because they wish to explore ‘lost’ areas of knowledge or have conversations with demons, but because it imparts them with a sense of connection with the past. In a culture where the edges of the present time are crumbling into the future at a rate that is often difficult to comprehend, the sense of connection to historical time is vague, to say the least. The contradictions of post-Capitalism have fragmented consensus reality to a point where alienation and powerlessness are endemic in our culture. Occultism offers an alternative: a sense of connection, perhaps, to a historical time when the world was less complicated, where individuals were more in touch with their environment, and, had more personal control over their lives. Occultism, and the subjects within it, strive to look at basic questions: “Where am I going?”, “How will I get there?”, “How much fun can I have on the way?”. Occultism offers possibilities – that which has not been explained by science; capabilities we may have which go beyond our accepted limitations; powers that we can tap into to change ourselves, and our world. Science does not have the enduring quality that occultism can offer. Science is changing too fast. Most of us are operating on a view of reality set up by Newton (an alchemist, by the way), whilst pure science is already beginning to find out where Einstein went wrong.

Science and the occult are wary bedfellows at the best of times. Most science is based on logic, which assumes universal axioms. This has proved to work very well for building bridges or smashing atoms, but less so when it comes to human beings. Logic is a descriptive tool, no more, and its limitations when applied to human behaviour are slowly becoming apparent. There’s parapsychology of course. Probably the most hotly contested area of science this century. And still not much nearer to ‘explaining’ the effects that it is monitoring. Scientists using the language of science to explain occult phenomena is almost as painful reading as occultists trying to do the same. Appropriating the terms of science though is necessary. We’ve come to expect it, especially in a society where ‘science’ sells washing powder and other basic necessities. Science gives something the stamp of authenticity in the same way that religion does. It needn’t even be ‘good’ science, so long as it sounds at least halfway plausible. The veracity of belief is the key, here. Go back a few centuries and the peasant-in-the-street would tell you that yes, the Gods were real and that if you kept them happy, they didn’t strike you down with a bolt of lightning. Unless you have a strong religious sense, it’s difficult to achieve this level of certainty nowadays. Instead, Gods can be thought of as metaphors, archetypes, role models, self-replicating morphogenetic fields, etc, etc. Moreover, you don’t need huge colonnades, vast temples, three thousand screaming worshippers, and a naked virgin on an altar to get their attention, all you need is a dab of incense, a meditation cushion, and some electro drone music. Yet, unaccountably, something wonderful may happen. This perhaps is the real place of the occult in modern society. Our world is so crowded with marvels and miracles that they have become commonplace to us; especially when we no longer see ourselves as miracles. We swim through the world, deafened by the buzz of machines and the flicker of the Videodrome, our senses are dulled from the information overload. Yet, shifting to another position, we suddenly find that the world is magical. That humanity is, as Alan Moore so eloquently put it, “unpredictable beyond the dreams of Heisenberg; the clay in which the forces that shape all things leave their fingerprints most clearly.”

If it is so simple, why can’t it be simply stated? Well, we tend to need a lot of convincing. The keys to change are not enough, we need a cultural backdrop in which to set them – systems of beliefs, maps, and explanations that allow us to stretch the credibility envelope to accommodate new ideas and perceptions. So we search for knowledge amongst books, books, and yet more books when it becomes increasingly plain that the answers are within our grasp. Entering the doorway marked ‘occult’ we find ourselves within a labyrinth, which offers packages to suit most tastes, from potboilers of ‘mysterious phenomena’ to hardcore books on magick. Most people tend to settle into one particular subject that excites them the most and participate to varying degrees. The first level of inquiry is, often as not, reading. The second level is practice, usually within the bounds of one or another of the many esoteric systems of knowledge. The third level is that of going beyond the boundaries within the occult – the gaps which are usually unmarketable, unattractive, and above all, personally risky. For me, the occult is a fascinating subject because it draws from the past and attempts to synthesize with the frontiers of science and technology, as well as art, philosophy, and social engineering. Occult practices (hopefully) lead the individual to look within, and also, at their social conditioning and adherence to belief structures. At the same time, occult practices can encourage the individual to look at the wider world; what’s going on, and what (if anything) we can do about it. It’s a meeting point in the cultural melting pot, where all avenues of exploration can meet, merge, and produce new syntheses. A node where ideas mutate each other and, those who wield them.

In many senses, occultism is an ‘escape route’ from the limitations of consensus reality. Some escape routes are well-signposted and, despite their surface gloss, mere dead-ends. We search for that which is ‘hidden’ from us and may come to discover that magick leads us back to ourselves, and the very basics of how we relate to each other and the world about us. That perhaps the really engrossing mysteries are those by which we live daily, on an unconscious basis – that which we tacitly take for granted. For me, the potential of occultism is less about becoming ‘spiritual’, and more about becoming spirited. We live, for the most part, in a dismembered world of things and objects. Magick may lead us to attempt to create a dialectical world of processes – where understanding, rather than explaining, is venerated; where differences are acknowledged, rather than merely being glossed over. The occult may offer the keys to understanding ourselves, but the will to do so must be ours. Else the occult becomes merely another arena in which we continue to act out the same games of power and control – being right, getting even, being ‘an expert, being better than so-and-so’. Make no mistake, the occult is permeated with the same word-viruses that permeate the rest of our culture, as is clearly shown in the rapid growth of spiritual consumerism. Popular occultism does not challenge anything. Unpopular occultism challenges consensus reality by enabling us to meet, head-on, our taboos, fears. Not to exorcise or explain them away, but to understand the power of these ‘monstrous souls’, and in understanding them, allow them to grow. This is a difficult and demanding task, more so because, while it is an essential part of occult development, it has been obscured and mythologized as somehow ‘sinister’. Our society has locked its collective demons away in a dark cellar. They have responded by rotting the foundations and occasionally flooding the streets with sewage.

Magick and mysticism are two poles of action within the occult. Magick is the way of action-in-the-world. Hence the phrase “Do What Thou Wilt.” Magick is about do-ing. Mysticism, however, is more associated with transcending reality or achieving zero states of enlightenment. Neither are mutually exclusive, however. But mysticism often requires a spiritual dimension of experience, whilst modern magick is becoming increasingly concerned with the world as we experience it, rather than the world as we tend to model it. After all, the map is not the territory. We might create temporary islands of order with which to zoom in on one particular part of our experience, but in the real world, so much of our experience is cast against a backdrop of chaotic terrain. We may search for ‘evidence’ of a grand plan behind the scenes, but what of the possibility that there may not be one? Why do we need to explain the world so completely anyway? The Uncertainty Principle itself assumes the status of a taboo, and to banish it we search for meaning through the shattered remains of past cultures, through a labyrinth of lost gods and hidden knowledge when we know, deep down, that knowledge alone cannot fulfill the void in our hearts, that wisdom springs from experience and the mindful application of learning and insight. Occultism may give us a link to the past, but it also reminds us that the present is continually changing and that individuals participate in their own futures. The questions that occultism addresses are changing as society changes, as we dream of new possibilities of what we might become.

It is the constant mutation and diversification of contemporary occultism that gives it its postmodern flavour – new magical systems and diversifications are being created all the time. All limitations have been thrown off, and today’s magicians are equally likely to be interested in the more novel applications of high technology as they are the more traditional tools of magick. Witness the growth of ‘oracular’ performance art, which directly draws upon shamanic techniques such as suspension, body piercing, and trance states. Artists are returning to shamanistic practices, and it is also worth noting that modern magicians are usually occupied with one or more creative endeavors, be it writing, artwork, music, or multimedia using computers. An important part of the magical process is the ‘earthing’ of ideas and flashes of illumination into consensus reality so that they can be transmitted and left for others to use as ‘signposts’ for their own progression. Modern occultism can thus be characterized as an exercise in Collage.

This is an age of magick, where reality can be manipulated, twisted, served up for entertainment, and likewise shattered for fun, profit, & control. Even our chosen escape routes feed the beast. Cracking open a new novel, freshly smelling of shrink-wrap and clean pages, I settle back and delve into a larger-than-life narrative outlined in clear, crisp serifs and quickfire bursts of prose. Walking down a street at sunset, striding with a sense of purpose, shades angled for maximum coverage. From a window, a heavy bass line growls into gear, followed by sawtooth guitars. The sounds, the street, sundown & shades form a composite scene; and I realize – I’m in a movie. Like many modern films, it has good sets, and wild special effects, but the script leaves something to be desired.

Desire. All aspirations and desires have been carefully packaged and subsumed into the structure of commodities. Even the most intrepid psychonaut must eventually, it seems, move into the marketplace. Pre-packaged realities eye each other, juggling for position. You only have so much time to devote to any one style. So which is it to be? The only stable principle is pleasure – from whatever you draw your kicks, no matter your justifications, noble or otherwise. We tend to go for the simplest solutions – beliefs in a bag, stereotypes, and ideals in bite-size take-home portions. Fast-Dumped into our minds, hard-wired in through social conditioning and everyday/extraday experience, they form the bedrock on which we build the shining cities of self, dream, and ideal. The whiter the city, the deeper, more convoluted the sewers that support it.

We are not encouraged to go for ‘the big picture’, except through the accepted routes of isms and ists, whereby the imagination is fed through logic gates, carefully screened, directed, curtailed, and manicured. Going for ‘the big picture’ conjures up images of psychic panic …paranoia or other forms of socialized madness where our none-too-stable coping strategies fail under the information overload. If you want to glimpse the big picture, then you’d better wear shades, or better still, blinkers. Reality is at fault; please do not adjust your mind.

We are all engaged in the evolution of the beast, at once both passive and active. Passive in that we can observe what happens to ourselves, and active in that we do participate at many levels, in the continual reflection and intensification of symbols and images that are all around us. In our heads and lurking in every square meter of territory to assault and engage our senses. Reality becomes a sea of dreams on which any individual or group can form islands built from images, symbols, clusters of belief, and viral ideas. This is the realm of the magicians, who are able to adroitly manipulate images without any apparent effort. Some may be highly visible as celebrities, media darlings, and walking talking ciphers for the projection and intensification of charismatic power. The most successful are the adepts of the invisible. Not so much hidden masters from Tibet as those who can “gosub” direct to the Deep Mind – those who can pull strings without us being aware of the fact. Puppeteers in the inner theatre of the mind. Slipping in a word here, a phrase there. A blip across our screen, and they’re gone.

Art imitates life. In the inner theatre, it pays off not to be stage centre, in full view of the lights. No, to be on the periphery is better, or best yet, to be part of the scenery. Here, the most deadly predators are the ones that we (as the audience) have grown used to. If a thing becomes ‘known’, it is often dismissed as harmless, or irrelevant, or we become ‘wise’ to its games. Alas, appearances can be deceptive.

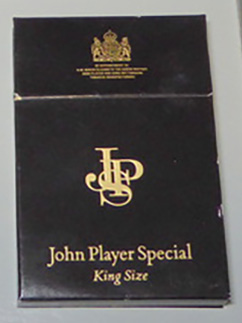

Sitting in a smoke-filled pub, against a background buzz of deals, assignations, and remixed dub, I focus in on a packet of John Player Specials. Black and gold project the image – corporate desire sigilised. A black formula one racing car curves a graceful arc around an s-bend in my brain. Gold is quality. Black evokes associations at once simple, elegant, and hi-tech. Like some billionaire’s coffin, the packet commands the visual field. An everyday object, yet loaded with images, associations, and memories. An icon of the hyperreal. Continually mutating, looping time and image back on itself as fashions are revived, reach a sudden peak and are cast into the strata of subcultures. Reality becoming a virtual field, constantly recycled through walkmans, videos, computer images, televisions, and playbacks. Suddenly our replication systems have a new dimension to them, faster than we can evolve a framework to fit them into. Whilst the effects of visual images are only just being chartered, the digital revolution is on us. Lila, illusion, spins her net and we are enmeshed in images under other images, dancing to songs hidden in other songs, and lulled to sleep by false promises lurking within other messages. As hackers of the hyperreal, we have to lever images apart, disentangling the webs, charting the temporary tunnels, climbing invisible mountains, and slipping between the cracks in the solid foundations of the world which wraps around us. Such is the role of the occultist in postmodern culture.