Armed Yogis – II

In the first post in this series, I introduced the subject of armed yogis – a concept which does much to perturb the common representation of yogis as peaceful ascetics given to inward, spiritual pursuits and generally unconcerned with the trappings of the material world.

What prompted me to come back was a recent twitter discussion about Aleister Crowley’s understanding of the Yogasutra of Patanjali. As is well-known, Crowley brought together the practice (and to some extent the theory) of Yoga with Western Ceremonial Magick – arguing that Yoga and Ceremonial Magick are two sides of the same coin. What particularly struck me during my various random thoughts on Crowley though, was a quote from his 1943 work Magick Without Tears:

“…my system can be divided into two parts. Apparently diametrically opposed, but at the end converging, the one helping the other until the final method of progress partakes equally of both elements. For convenience, I shall call the first method Magick, and the second method Yoga. The opposition between these is very plain for the direction of Magick is wholly outward, that of Yoga wholly inward.”

What interests me here was the assertion that Magick is “outward” – that is to say, directed towards the world and Yoga “wholly inward”. This is a common enough interpretation of the apparent difference between magic and yoga – or magic and mysticism (as ‘Yoga’ often gets described as a mystical pursuit) and I think its easy to see the traces of larger, colonial-era distinctions between the active, outgoing West and the passive, unworldly “mystic East” implicit in the distinction between magic and yoga. It’s the figure of the armed yogi, the warrior-ascetic – even the yogi as magician or sorcerer – which disrupts this kind of binary distinction. As J. N. Farquhar put it (1925, p433): “The idea of Hindu monks becoming fighting men seems grotesquely absurd.”

In order to explore this further, let’s begin with a battle. The Battle of Buxar (October 22, 1764) is considered to be a major turning point in the British control of India. Against the forces of the East India Company, commanded by Hector Munro, were the combined armies of Mir Qasim, Nawab of Bengal, the Nawab of Awadh, and the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II. The forces of the East India Company carried the day. The outcome of Buxar was the Treaty of Allahabad, between the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II and Robert Clive of the East India Company. Alam granted the Company Diwani – the right to collect tax revenue from the peoples of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa – control over an eighth of South Asia’s population and territory. Among the troops defeated at Buxar was a force of between 5-6,000 described in accounts as gosains or nagas.

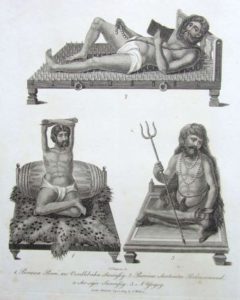

Who were these warriors? In East India Company reports and accounts there are a number of terms – often used interchangeably to denote these warriors – Bairagis, Sannyasis, Gosains, Nagas, Yogis, and Fakirs. In actuality, these were members of the ten orders of Daśānamī Sannyāsīs. For a full account of the Daśānamī order, see Matthew Clarke’s 2006 book “The Daśānamī-Saṃnyāsīs: The Integration of Ascetic Orders into a Lineage” (Brill 2006). A key distinction is that gosains refers to Daśānamīs who have adopted a sendentary lifestyle, are sometimes married, and lived in maṭhas – monastic settlements, and nagas refers to those Daśānamīs who went about naked or wearing only a loincloth, smeared their bodies with ashes, and lived in akhāṛās (“wrestling arena”) – military encampments (in some cases, actual fortresses) where they would train for fighting under the leadership of mahants. As I noted in the previous post, the general scholarly consensus is that the militarisation of the Nagas took place between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and there are many accounts of local regents employing troops of nagas as mercenaries. They were feared as much for their yogic powers as their martial prowess. When they were not fighting, they continued with their ascetic lifestyle, attending festivals along pilgrimage routes.

George Bruce Malleson (1914, p189) describes a encounter between East India Company forces and “5,000 naked fanatics” at the battle of Patna in May, 1764 in which “The fanatics rushed forwards, with great impetuosity, with wild shrieks and gestures, presenting a very formidable appearance; but the English received them with a volley so well-directed, that many of them were laid low and the remainder scattered in disorder.”

The Maṭhas were not only monastic settlements. Under royal and Mughal patronage, they became centres of trade and commerce. The Daśānamīs formed trading networks, doubtless aided by their military prowess. They also received land grants which were not subject to taxes and also, pensions.

In addition to the Śaiva Daśānamīs there were other militarised orders such as the Sufi Faqīrs (“Fakirs”), the Ram-worshipping Dādūpanthīs, and the Vaiṣṇava Rāmānandīs – also known as bairagis.

Historical records indicate that when these militarised orders were not fighting for patrons, they fought each other. Farquhar (1925, p29) cites an account from in which sannyāsīs of the Giri sub-order (of the Daśānamīs) took control of the Kumbh Mela at Haridwar and collected revenue from the pilgrims attending. In 1760, members of the bairāgīs fought a battle with the Giris for control of the festival, which according to this report, left 18,000 bairāgīs “dead on the field”.

What was the British attitude to these fighting ascetics? The activities of the Daśānamīs and other groups – participating in trade, money-lending, going about naked and engaging in military campaigns did not accord with European notions of what constituted appropriate religious practice. James Forbes, an eighteenth-century East India Company merchant says of them:

“These gymnosophists [ascetics] often unite in large armed bodies and perform pilgrimages to the sacred rivers and celebrated temples; but they are more like an army marching through a province than an assembly of saints in procession to a temple, and often they lay the country through which they pass under contribution.” 1

Although there are some recorded instances of the British employing sannyāsīs as spies, mercenaries, couriers, translators and guides (see Sinha, 2008, pp15-18) they were generally seen as a threat to Colonial rule. Warren Hastings (the first de facto Governor-General of India, 1773-1785) described the militarised ascetics as “A set of lawless bandette [who have] infested these countries and under the pretence of religious pilgrimage have been accustomed to traverse the chief part of Bengal, begging, stealing and plundering whereever they go.”

In January 1773 Hastings issued a proclamation barring “all Biraugies and Sunnasses who are travellers strangers and passengers in this country” from the provinces of Bengal and Bihar, save for “such of the cast of Rammanundar and Goraak [Ramanand and Gorakhnath] who have for a long time been settled and receive a maintenance in land money . . . from the Government or the Zemindars of the province, [and] likewise such Sunasses as are allowed charity ground for executing religious offices.” 2

Hastings’ proclamation makes a distinction between travelling ascetics and those who are settled. The spectre of dangerous unregulated, wandering groups would recur again in the anti-thug campaigns of the early nineteenth-century, more of which in a future post.

In a letter of the same year, Hastings recounts an encounter between sannyāsīs and Company troops:

“About a month ago intelligence was received by the Collector of Rungpore that a body of these men had come into his District and were plundering and ravaging the villages as usual. Upon this he immediately dispatched Capt. Thomas with a small party of Pergunnah Seapoys, or those troops who were employed only in the Collections, to try and repress them. Capt. Thomas soon came up with them and attacked them with considerable advantage, but his seapoys imprudently expending their ammunition and getting into confusion, they were at length totally defeated and Capt. Thomas, with almost the whole party, cut off. This affair, although disagreeable on account of the death of a gallant officer, can have no other bad consequence, as we have taken proper steps to (subject) these people to a severe chastisement, and at all events to drive them from the country, and we hope from the precautions which we now find it necessary to take, of stationing a more considerable force on these frontiers, effectually to put an end in the future incursions of the Sunnasses.” 3

In a letter dated March 31, 1773, Hastings reports that “Four Battalions of Sepoys” are engaging in anti-sannyāsī patrolling, and complains that “it is remarkable that we meet obstacles every day in the superstition of the inhabitants, who in spite of the cruelties and oppressions which they undergo from these people are so bigoted in their veneration of them as to endeavour on every occasion to screen them from the punishment which they are exposed to from our Government” (Jones, 1918, p217).

Further proclamations effectively barred armed ascetic troops from moving at will through British-controlled territories, on pain of detention. Hastings also stated that such groups were to be considered enemies of the government. Hastings also banned public nakedness, apart from at religious festivals. 4 Not only were armed yogis seen as dangerous due to their martial prowess, they quickly came to represent those elements of Hinduism which were depraved and superstitious and required eradication or at the very least, control.

Other sources of tension came over the armed ascetics collection of “tribute” from villages. Dana (“giving”) is an important part of Hindu dharma. As itinerant ascetics passed through villages they would receive Dana in the form of money or food – an act which went far beyond a mere economic exchange but marked the mutual support and respect between religious specialists and the laity. However, the British tended to characterize these transactions in terms of spurious holy men preying on ignorant and gullible villagers. It also hindered the steady collection of revenue by the British. The authorities also clashed with the ascetic orders over their landholdings. British attempts to force ascetics into paying revenue was taken as an insult to their religious rights and privileges. Bhattacharya (2012, p90) cites reports of sannyāsī wounding themselves with knives as a form of public protest. Hastings also pressed regional rulers to rid themselves of any sannyāsī troops in their employ.

Eventually, the tensions between the East India Company and the armed yogis resulted in what has been called the ‘Sanyassi Rebellion’ – the events of which I shall examine in the next post.

Sources

Ananda Bhattacharya Reconsidering the Sannyasi Rebellion Social Scientist, Vol. 40, No. 3/4 (March-April 2012).

Matthew Clark, The Daśanāmī-Saṃnyāsīs: The Integration of Ascetic Lineages into an Order. Brill, 2006.

Timothy S. Dobe Hindu Christian Faqir: Modern Monks, Global Christianity, and Indian Sainthood Oxford University Press, 2015.

J.N. Farquhar The Fighting Ascetics of India The John Rylands Library, 1925.

Mary E Monckton Jones Warren Hastings in Bengal, 1772-1774, with appendixes of hitherto unpublished documents Clarendon Press 1918.

David Lorenzen Warrior Ascetics in Indian History Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol.98, No.1 (Jan-Mar., 1978), pp61-75.

George Bruce Malleson The Decisive Battles Of India From 1746 To 1849 Reeves & Turner 1914.

William Pinch Peasants and Monks in British India University of California Press 1996.

Nitin Sinha Mobility, control and criminality in early colonial India,1760s-1850s Indian Economic Social History Review 2008; 45; 1.

Notes: